After another year marked by great power rivalries, rising security risks, a series of coups, land grabs, outright war and shifting strategic alignments, the role of hegemonic, middle and rising powers has become more more fluid than at any time since the end of the Cold War. Looking ahead to 2024, various analysts respond to us whether they agree or disagree with the following statement: Will next year confirm that the world is moving rapidly towards greater multipolarity or 'non-alignment'?

(Senior Research Fellow at the Center for the Advancement of Scholarship, University of Pretoria)

Next year we will not see greater multipolarity, but rather greater bipolarity. China has replaced Russia as the United States' main competitor in a new cold war that has less to do with ideology and more to do with markets and technology. China's $18 trillion economy has already surpassed that of the 27-nation European Union combined, and China is the largest trading partner of more than 120 countries. Its One Belt, One Road initiative continues to build infrastructure around the world, and the $100 billion Beijing-based Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank has 109 members representing 80% of the world's population. .

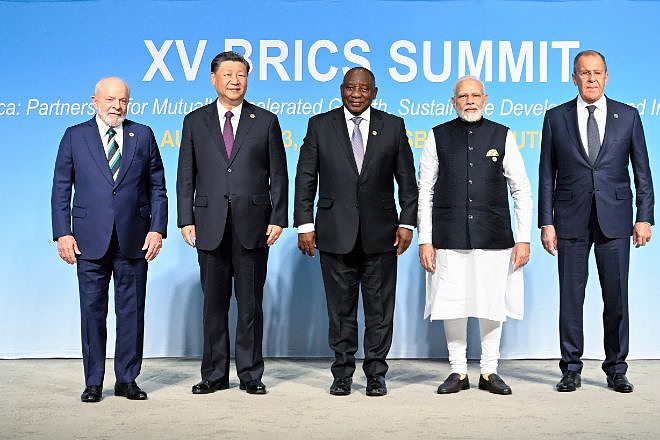

In January, the Chinese-dominated BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) will expand to include Argentina, Ethiopia, Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Many of these Global South countries have refused to condemn Russia's invasion of Ukraine. And now they intend to promote the 120-member Non-Aligned Movement, which emerged from the Bandung Conference of Asian and African governments in 1955. As part of a strategy to avoid getting caught up in superpower conflicts (at that time, between the Americans and the Soviets), the members of this Movement refrained from sealing collective defense agreements with either party. This weapon of the weak gave impetus to efforts to enhance regional autonomy and strengthen global governance institutions like the United Nations, and perhaps will do so again.

Finally, Israel's siege and bombing of Gaza in response to the Hamas attack (in which 1,400 Israelis were killed) have resulted (at the time of writing) in more than 9,000 dead and 1.4 million Palestinians displaced. Failure to challenge Western support for Israel will expose double standards within the international system, further weakening global support for Ukraine in 2024.

(Founder and President of Eurasia Group and GZERO Media).

Indeed, the international trend towards "non-alignment" will continue in 2024. But "multipolarity" is a different question, which depends on the area of competition we are thinking about.

In 2024, non-alignment for many countries will mean recognizing that openly taking sides in the growing rivalry between the United States and China is a losing proposition. Some governments, particularly in countries located near China or Russia, will view the United States as an indispensable security partner. But the trade alliance with China remains essential for future growth.

Multipolarity is a more complex issue. In the security sphere, we will live in a unipolar world. Only the United States can protect power in all regions of the world. China's military weight is growing, but - and this is important - it has not yet been tested by open war in more than four decades. Russia's conventional forces were bereft even before its full-scale invasion of Ukraine inflicted generational damage on its military capabilities. And Europe still depends on the United States, as do American allies in Asia.

In the economic field, however, we are undoubtedly living in a multipolar world, in which the United States, China, Europe and India are crucial actors in restoring stability and dynamism to the global economy. Then there is the digital realm, where the power of governments is limited by the power of the technology companies that produce the advances that political officials struggle to understand. In this sense, we are facing an emerging "technopolar" world, in which governments and technology companies will forge power for the foreseeable future.

If we put all these trends together, non-alignment is the wave of the future.

(Professor at Dartmouth College and visiting professor at Stockholm University).

Multipolarity is a myth, as I recently argued with William Wohlforth in Foreign Affairs. The United States has indeed become less dominant than it was in the 1990s, when it was more advanced militarily, economically, and technologically than any state had been before. But a multipolar world is a world with three or more leading powers more or less equal at the top of the international set. Who could play that role today? Of all the countries that could possibly rank third - France, Germany, India, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom - none are even close to the United States or China.

Not only is multipolarity a myth, but the system remains closer to unipolarity than Cold War-style bipolarity. Although China is on the rise, the world's widening power gap will take a long time to close.

China has risen more significantly in the economic arena (although less than commonly assumed, as it significantly inflates its GDP data), but has done much less to narrow the power gap in other areas. It continues to lag far behind the United States in technological terms.

A soon-to-be-published book (which I wrote with other authors) shows that American companies have a 53% profit rate in high-tech industries, compared to just 6% in China.

China is also only a regional military power, and that will remain the case for quite some time, leaving the United States as the only superpower that can command the common heritage.

(Former US Undersecretary of State for Global Affairs (2001-09), is a senior fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at the Harvard Kennedy School.)

Russia's invasion of Ukraine has unleashed significant geopolitical changes. The war, along with rising tensions between the United States and China, has unified the transatlantic community and urged many governments in the Indo-Pacific region to bolster their defenses and secure their supply chains. The same developments have also encouraged political leaders across the Global South to pursue “optionality,” making decisions informed by their national interests while doing everything possible not to get caught up in great power disputes. .

The geopolitical changes underway today include new or closer national alignments – from deepening Russia's ties with China, Iran and North Korea, to Australia's collaboration with India and Indonesia, and with the United States and the United Kingdom. under the Aukus alliance. While the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue between Australia, India, Japan and the United States (established in 2007) has become more ambitious, other powers have had a hard time preventing emerging new alignments. Many see Hamas' latest attack on Israel as an attempt to block normalization between the Saudis and Israelis, which could have threatened not only Hamas but also its backers in Iran.

The chaotic US withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 contributed to this evolution in the international system by undermining perceptions of US credibility, reliability, and effectiveness. That, in turn, caused some leaders, such as Russian President Vladimir Putin, to reassess the costs of implementing policies contrary to US interests. These shifts in preference and perspective have facilitated not only new waves of violence, but also new or different relationships, as America's allies, rivals, and enemies recalibrate their objectives. Likewise, Russia's failed war effort in Ukraine appears to have created a more permissive context for Azerbaijan's conquest of Nagorno-Karabakh. New wars and the desire not to end up immersed in conflicts between the United States, Russia and China will continue to drive the new multipolarity and the return of non-alignment.

(Research professor at Boston University's Pardee School of Global Studies.)

Great power competition will continue in 2024, as will the rise of non-alignment, albeit now embodied in a new version: active non-alignment (NAA). Originally caused by American and Chinese pressure on Latin American countries to take sides in their brewing cold war, the NAA is now spreading across Africa and Asia. It takes a page from the Non-Aligned Movement of times past, but adapts it to the realities of the new century.

The NAA should not be confused with neutrality or equidistance. Rather, it is a dynamic concept that allows countries to have different positions depending on the issue at hand. As a foreign policy doctrine, it means putting the interests of one's own country first and not succumbing to the pressures of great powers. It requires highly developed analytical skills, so that each issue can be evaluated on its own merits.

The rise of the NAA has become especially evident following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, when many countries across the Global South have refused to take sides. This development demonstrates that the main division in the world today is not between democracy and autocracy, but between the Global North and the Global South. The spread of the NAA is closely associated with the rise of the Global South as a significant force in world affairs, of which the recent expansion of the BRICS is an example. The best example of this in practice is the foreign policy of Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva over the course of 2023.

(Former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Spain, she is a visiting professor at Georgetown University).

If recent events are any indication, the world is indeed accelerating the pace toward a realignment. Russia's war in Ukraine, ethnic displacement in Nagorno-Karabakh, the series of coups in Africa and the crisis in the Middle East are all signs of the disruption of the world order that emerged after World War II. These events are not atypical events or isolated crises. The United States is somewhat withdrawn and less assertive than in the past, and countries and non-state actors feel emboldened to take risks and seize opportunities that they had previously avoided.

The current moment is characterized by an alphabet soup of new coalitions that have formed in response to changing global power dynamics. The expansion of the BRICS is just one example among many. Increasingly, middle powers seek to exert global influence and so we have entered an era of disorder that will last until a new configuration of international relations is solidified.

(Senior Research Fellow on China at the Asia-Pacific Program at Chatham House.)

I agree. In the midst of a scenario of countless crises and elections, 2024 will be another geopolitically tumultuous year. But it also offers opportunities for non-Western powers that want "neutrality" and "non-alignment" to play a greater role in global affairs. Most of these countries, including China, base their foreign policy priorities on hard calculations of economic or political interests, while the collective West emphasizes the importance of "like-mindedness."

This current situation cannot but create greater multipolarity. Pragmatism will require many countries to take sides depending on the issue at hand. While "neutrality" will remain unthinkable from the perspective of G7 members - whether in terms of relations with China or the war between Israel and Hamas - many non-Western powers will consider it de rigueur when carrying out their foreign affairs.

For its part, China will continue to push the rest of the world toward greater multipolarity, as it sees that as the best way to manage its stagnant relationship with the United States. While China's initial position on Russia's war in Ukraine worsened its ties with many Western countries, attitudes within the West have since become more complex. There is now a strange mix of fear that China will help the Kremlin militarily, but also hopes that it will limit President Vladimir Putin's nuclear brinkmanship.

Since many countries around the world do not see today's geopolitical crises in absolutely black and white, China may find that its preference for multipolarity is becoming an asset.

What is chloropicrin, the chemical agent that Washington accuses Moscow of using in Ukraine?

What is chloropicrin, the chemical agent that Washington accuses Moscow of using in Ukraine? Poland, big winner of European enlargement

Poland, big winner of European enlargement In Israel, step-by-step negotiations for a ceasefire in the Gaza Strip

In Israel, step-by-step negotiations for a ceasefire in the Gaza Strip BBVA ADRs fall almost 2% on Wall Street

BBVA ADRs fall almost 2% on Wall Street Children born thanks to PMA do not have more cancers than others

Children born thanks to PMA do not have more cancers than others Breast cancer: less than one in two French women follow screening recommendations

Breast cancer: less than one in two French women follow screening recommendations “Dazzling” symptoms, 5,000 deaths per year, non-existent vaccine... What is Lassa fever, a case of which has been identified in Île-de-France?

“Dazzling” symptoms, 5,000 deaths per year, non-existent vaccine... What is Lassa fever, a case of which has been identified in Île-de-France? Sánchez cancels his agenda and considers resigning: "I need to stop and reflect"

Sánchez cancels his agenda and considers resigning: "I need to stop and reflect" “Amazon product tester”: the gendarmerie warns of this new kind of scam

“Amazon product tester”: the gendarmerie warns of this new kind of scam “Unjustified allegations”, “promotion of illicit products”… Half of the influencers controlled in 2023 caught by fraud repression

“Unjustified allegations”, “promotion of illicit products”… Half of the influencers controlled in 2023 caught by fraud repression Extension of the RER E: Gabriel Attal welcomes a “popular” ecology project

Extension of the RER E: Gabriel Attal welcomes a “popular” ecology project WeWork will close 8 of its 20 shared offices in France

WeWork will close 8 of its 20 shared offices in France “We were robbed of this dignity”: Paul Auster’s wife denounces the betrayal of a family friend

“We were robbed of this dignity”: Paul Auster’s wife denounces the betrayal of a family friend A masterclass for parents to fill in their gaps before Taylor Swift concerts

A masterclass for parents to fill in their gaps before Taylor Swift concerts Jean Reno publishes his first novel Emma on May 16

Jean Reno publishes his first novel Emma on May 16 Cannes Film Festival: Meryl Streep awarded an honorary Palme d’Or

Cannes Film Festival: Meryl Streep awarded an honorary Palme d’Or Omoda 7, another Chinese car that could be manufactured in Spain

Omoda 7, another Chinese car that could be manufactured in Spain BYD chooses CA Auto Bank as financial partner in Spain

BYD chooses CA Auto Bank as financial partner in Spain Tesla and Baidu sign key agreement to boost development of autonomous driving

Tesla and Baidu sign key agreement to boost development of autonomous driving Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV The home mortgage firm rises 3.8% in February and the average interest moderates to 3.33%

The home mortgage firm rises 3.8% in February and the average interest moderates to 3.33% This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Europeans: a senior official on the National Rally list

Europeans: a senior official on the National Rally list Blockade of Sciences Po: the right denounces a “drift”, the government charges the rebels

Blockade of Sciences Po: the right denounces a “drift”, the government charges the rebels Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Champions Cup: Toulouse with Flament and Kinghorn against Harlequins, Ramos replacing

Champions Cup: Toulouse with Flament and Kinghorn against Harlequins, Ramos replacing Tennis: still injured in the arm, Alcaraz withdraws from the Masters 1000 in Rome

Tennis: still injured in the arm, Alcaraz withdraws from the Masters 1000 in Rome Sailing: “Like a house that threatens to collapse”, Clarisse Crémer exhausted and in tears aboard her damaged boat

Sailing: “Like a house that threatens to collapse”, Clarisse Crémer exhausted and in tears aboard her damaged boat NBA: Patrick Beverley loses his temper and throws balls at Pacers fans

NBA: Patrick Beverley loses his temper and throws balls at Pacers fans