The shortage of skilled workers is developing into the biggest brake on growth in Germany. The problem is exacerbated by the persistently high rate of school dropouts. In 2021, 47,500 young people left general schools without a secondary school certificate. At 6.2 percent, their share was slightly higher than in previous years, as a study by the Bertelsmann Foundation shows. Almost every fifth person in the 20 to 35 age group remains without completed vocational training.

The country is “to a large extent a waste of human potential”, criticizes the renowned educational researcher Klaus Klemm, who prepared the study. And because the situation in schools has recently deteriorated significantly, more and more young people are threatening to end their school days without sufficient knowledge.

The goal of reducing the school drop-out rate has been at the top of the agenda for education politicians in the federal and state governments for years. However, with slight fluctuations, the share has remained constant at around six percent since 2011. However, as the Bertelsmann study shows, there are significant differences between the individual federal states.

Bremen leads the school drop-out population with a share of ten percent, followed by Saxony-Anhalt (9.6), Thuringia (8.3) and Saxony (8.2). Bavaria and Hesse, on the other hand, are better off, where a good five percent of young people do not even achieve the simplest school-leaving certificate.

And while the situation in Bremen, but also in Rhineland-Palatinate, has actually deteriorated over the years, Berlin has reduced the proportion of school leavers without a degree from 11.2 percent in 2015 to 6.7 percent most recently. The positive development in the capital is surprising, especially since Berlin regularly comes off particularly badly in almost all educational comparisons.

In addition, Klemm therefore also uses the performance of ninth graders in his educational statistical analysis as part of the nationwide IQB educational trends, which the Institute for Quality Development in Education at Berlin's Humboldt University regularly prepares for the Minister of Education.

It shows that the percentage of students who do not meet the minimum standards in German and mathematics in the tests often do not match the respective school dropout rates of the countries. Thuringia and Saxony, for example, have relatively few ninth graders who end up in the bottom segment in the comparative tests, but significantly higher proportions of school leavers without a degree.

Bremen and Berlin occupy the last places in the comparative tests. And in both city-states, the proportion of ninth graders with insufficient German and mathematics skills is higher than the school dropout rate. "The suitability of the lower secondary school leaving certificate as an indicator, for example for the readiness for training, is questionable," concludes the director of the Bertelsmann Foundation, Dirk Zorn.

Girls are more likely than boys to complete at least a lower secondary school certificate: only 38 percent of those who drop out of school are women.

Ethnic origin plays an even greater role than gender: 13.4 percent of young people from abroad do not achieve a degree, which is three times more common than Germans.

A distinction based on migration background would be more meaningful. However, according to the study, such nationwide data does not exist for school leaving certificates. With regard to foreign students, the difference between the federal states is striking.

While in Bremen, Saxony and Thuringia almost every fourth foreign school leaver does not graduate, this applies to only 5.7 percent in the capital and only around four percent in Brandenburg. Moreover, Brandenburg and Berlin are the only federal states in which German school leavers are slightly more likely than young foreigners to have no qualifications.

However, education expert Klemm himself points out the limited informative value of these statistics. On the one hand, many former foreign children have now acquired German citizenship and are therefore no longer considered foreigners.

On the other hand, immigration has changed significantly in recent years. Until 2014, EU citizens made up the bulk of the migrants, while in the following years the immigration of refugees from Syria and other third countries dominated.

Without a degree, it is difficult for school leavers to gain a foothold in the labor market. Only one in four from this group started dual vocational training in 2020, another three percent began full-time school-based vocational training.

By far the largest part (70 percent) ended up in the so-called transition area, where attempts are made to provide young people with initial professional qualifications. Ideally, they even get a school-leaving certificate here, which, however, succeeds in at most every 20th case. Overall, the prospects of young people in the transition area rarely improve.

In view of the shortage of skilled workers, this waste of human potential is a disaster for the economy. In almost all industrialized countries, the proportion of young adults between the ages of 25 and 34 who have had little or no schooling has declined over the past decade. This is shown by the Education Study 2022 by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Usually even clearly.

In Germany, however, this proportion has increased and is now 14 percent. Almost every fifth person under the age of thirty has not completed vocational training. Here, too, the trend is upwards.

The corona crisis with the particularly long school closures in international comparison has exacerbated the educational misery. But the German Teachers' Association sees the schools increasingly burdened by the strong immigration, especially since there is a shortage of teachers nationwide.

The most recent IQB comparative test among fourth graders shows how dramatic the downward trend is. The proportion of children who fail the minimum requirements in arithmetic, reading and writing has risen significantly to more than 20 percent since 2016. However, the significant drop in performance also affects all higher skill levels, as the IQB study emphasizes.

The gap between German children and children with a migration background is widening. In Berlin, Bremen, Baden-Württemberg, North Rhine-Westphalia and Hesse, almost half of the students now have foreign roots.

"Everything on shares" is the daily stock exchange shot from the WELT business editorial team. Every morning from 7 a.m. with the financial journalists from WELT. For stock market experts and beginners. Subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Amazon Music and Deezer. Or directly via RSS feed.

Poland, big winner of European enlargement

Poland, big winner of European enlargement In Israel, step-by-step negotiations for a ceasefire in the Gaza Strip

In Israel, step-by-step negotiations for a ceasefire in the Gaza Strip BBVA ADRs fall almost 2% on Wall Street

BBVA ADRs fall almost 2% on Wall Street Ukraine has lost 10 million inhabitants since 2001... and could lose as many by 2050

Ukraine has lost 10 million inhabitants since 2001... and could lose as many by 2050 Sánchez cancels his agenda and considers resigning: "I need to stop and reflect"

Sánchez cancels his agenda and considers resigning: "I need to stop and reflect" The Federal Committee of the PSOE interrupts the event to take to the streets with the militants

The Federal Committee of the PSOE interrupts the event to take to the streets with the militants Repsol: "We want to lead generative AI to guarantee its benefits and avoid risks"

Repsol: "We want to lead generative AI to guarantee its benefits and avoid risks" Osteoarthritis: an innovation to improve its management

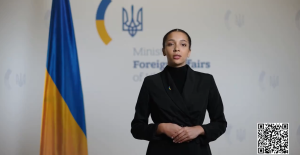

Osteoarthritis: an innovation to improve its management Ukraine gets a spokesperson generated by artificial intelligence

Ukraine gets a spokesperson generated by artificial intelligence The French will take advantage of the May bridges to explore France

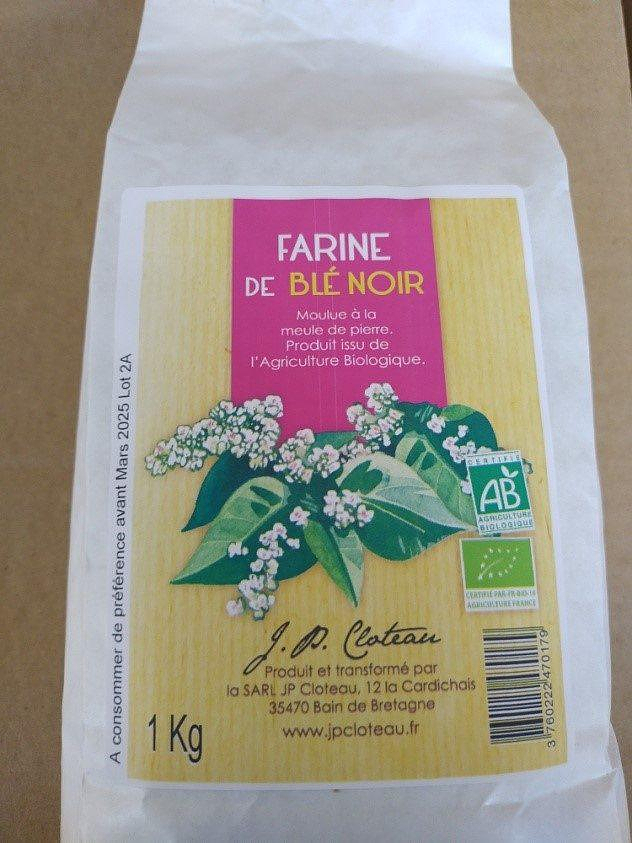

The French will take advantage of the May bridges to explore France Organic flour contaminated by a recalled toxic plant

Organic flour contaminated by a recalled toxic plant 2024 Olympics: Parisian garbage collectors have filed a strike notice

2024 Olympics: Parisian garbage collectors have filed a strike notice Death of Paul Auster: Actes Sud says he is “lucky” to have been his publisher in France

Death of Paul Auster: Actes Sud says he is “lucky” to have been his publisher in France Lang Lang, the most French of Chinese pianists

Lang Lang, the most French of Chinese pianists Author of the “New York Trilogy”, American novelist Paul Auster has died at the age of 77

Author of the “New York Trilogy”, American novelist Paul Auster has died at the age of 77 To the End of the World, The Stolen Painting, Border Line... Films to watch this week

To the End of the World, The Stolen Painting, Border Line... Films to watch this week Omoda 7, another Chinese car that could be manufactured in Spain

Omoda 7, another Chinese car that could be manufactured in Spain BYD chooses CA Auto Bank as financial partner in Spain

BYD chooses CA Auto Bank as financial partner in Spain Tesla and Baidu sign key agreement to boost development of autonomous driving

Tesla and Baidu sign key agreement to boost development of autonomous driving Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV The home mortgage firm rises 3.8% in February and the average interest moderates to 3.33%

The home mortgage firm rises 3.8% in February and the average interest moderates to 3.33% This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Europeans: a senior official on the National Rally list

Europeans: a senior official on the National Rally list Blockade of Sciences Po: the right denounces a “drift”, the government charges the rebels

Blockade of Sciences Po: the right denounces a “drift”, the government charges the rebels Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Top 14: Fijian hooker Narisia leaves Racing 92 and signs for Oyonnax

Top 14: Fijian hooker Narisia leaves Racing 92 and signs for Oyonnax Europa League: Jean-Louis Gasset is “wary” of Atalanta, an “atypical team”

Europa League: Jean-Louis Gasset is “wary” of Atalanta, an “atypical team” Europa League: “I don’t believe it…”, Gasset jokes about Aubameyang’s age

Europa League: “I don’t believe it…”, Gasset jokes about Aubameyang’s age Foot: Rupture of the cruciate ligaments for Sergino Dest (PSV), absent until 2025

Foot: Rupture of the cruciate ligaments for Sergino Dest (PSV), absent until 2025