One would not immediately think of saying that it was the work of the hour. Where never-before-seen intoxications of color and form can be animated via a smartphone app, images whose origins can be seen from afar must appear as if they have fallen out of time: anachronistic, outdated in terms of everyday life. But what can you do about the fact that you are once again standing in front of Emilio Vedova's abysmal gray painting, just as all the newspapers are reporting on their first experiences with the incredible ChatGPT intelligence?

It's true: Millions of retrievable data sets are not stored in the artist's brain. But no AI can match the obsessive density to which the available and unavailable in-images merge. When we visited the Italian artist in his Venetian studio in the 1980s, he was standing – tall – in front of a much larger canvas, and it looked as if he had just fought his way through a brambles.

The Ropac gallery in Salzburg is now showing a never-exhibited set, mostly from the 1990s by the painter, who died in 2006. It is these images from his late work whose graphic gestures still betray a volcanic excitement while they withdraw more and more into their secret. Black, white and all shades of gray in between form the coloristic standard. And color, where it sometimes surprises with green or blue shreds of cloud, is an ingredient, an interjection, an answer, an extension, but never the origin.

One could say: color now and then awakens the pictures from their dark dreams, and they never surpass the network of black strokes and brushstrokes with variegation. Most recently, Vedova left his painting to an unpredictable chemical fate with a translucent layer of varnish. The nitro emulsion leads to roughening and fine reliefs, and at times the cracked drawings are reminiscent of fossils, of fossil imprints on slabs of slate. Peter Sloterdijk could have included the images prominently in the canon of his gray philosophy.

For a long time, Emilio Vedova's work was the benchmark for Italian post-war art. Unlike in Germany, where the fashionable blossoming of non-representational art was a kind of catch-up action that wanted to achieve international modern standards again after the forced cultural standstill during National Socialism, Italian artists got much less caught up in the fundamental dispute. The abstraction that Vedova acknowledged from the beginning of the work was not a decision of conscience that would have been superior to a discredited realism.

The figurative pictorial language of Renato Guttuso attracted no less attention than the careful abstractions of Piero Dorazio. In Italy, negotiations took place in the country, which in Germany split into two political and cultural systems. And Emilio Vedova was later able to say quite non-polemically: “For me, abstract painting was never an evasion of urgent reality. I just wanted to express the feeling of presence in my paintings in a contemporary language.”

In 1946, together with Ennio Morlotti, Renato Guttuso and Giuseppe Santomaso, Vedova founded the artists' group "Fronte Nuovo delle Arti", which wanted to overcome the cultural dictates of the Mussolini years. Membership was a political commitment, not tied to style. In contrast to Guttuso, who switched to the neo-realist direction, not least under pressure from the head of the KPI, Togliatti, Vedova saw no reason to give up abstract pictorial writing, even though he joined the Communist Party in 1948 “in order to take a clear position”. Nothing would be more wrong than to misunderstand the decision to abstract as an escape from political concreteness.

He will never be quite the pure informal painter. To a certain extent, Vedova's pictures always remain eyewitnesses to the battlefield of life. And the commitment to the present is not just rhetoric. Whenever the unexplained reason for the picture called for more violent, powerful or even shrill tones, Vedova equipped his works with worn ropes, broken slats and clumsy blocks to create heavy material pictures, so that one could think one was standing in front of a wall of broken wood. The work thus breaks down into distinct sections and groups. It was never intended for repetition or recognisability. Only the titles return. “Venezia muore” – Venice is dying – are the names of five pictures in the Salzburg exhibition, and each one tells of how we dealt with the unavoidable death.

Emilio Vedova was caught up in his time and sometimes got tangled up in it like his German spiritual brother Georg Baselitz. A non-conformist, an independent, and if the term weren't thoroughly spoiled, a lateral thinker avant la lettre. Baselitz, the artist almost twenty years his junior, acquired a painting by Vedova in 1957: "Manifesto Universale" must have seemed like a contrary creed to him, who was busy recovering the figure. Painting as if under power, dynamic, eruptive, a discharge of black and white streaks, between which yellow, red and blue spots shimmer like exotic fish in an overgrown aquarium.

The closeness of the two artists has never led to adjustments, let alone harmonization. Seen as a whole, Vedova's work seems more cohesive. Even if it broke new ground with the “Plurimi” and the “Tondi” in the 1980s. It is precisely these round images that reinforce the frameless all-over structure that characterizes Vedova's painting. At that time, these large discs were experienced as energy fields on which the color forces flow from a center to all sides. The fact that the Italian began the sculptural expansion of painting with his "Plurimi" when Georg Baselitz entered the room with his monumental wooden figures is one of the beautiful coincidences of this artistic friendship, which was never about to be outdone.

“Emilio loved jumping from ambush,” Baselitz remembers, “he was a partisan, he loved the revolution, grand gestures, expressionism and me. But I'm not an Expressionist, I despise the revolution, at most we produce pictures, some of which are good ones. I then laughed at him and he looked at me helplessly.”

Laughter and helplessness may have found each other after all. If you look at Baselitz's late "Elke" pictures, then the intellectual proximity to the Italian with his irrepressible, untamed, erratically torn black is unmistakable. And so surrounded by Vedova's posthumous images, gripped by the nobility of their majestic unrest, one's pretty sure no AI bot, no matter how knowledgeable, will ever be able to rival them. It can be imitated in a highly professional manner, it can only be invented by the enigmatic organ, which consists of one part consciousness and two parts unconsciousness. Seen this way: maybe pictures of the hour after all!

Emilio Vedova, „Venice is dying“, bis zum 18. März 2023, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Salzburg

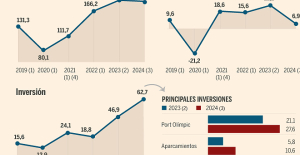

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives

War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte

First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025

Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025 Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Inflation rebounds in March in the United States, a few days before the Fed meeting

Inflation rebounds in March in the United States, a few days before the Fed meeting Video games: Blizzard cancels Blizzcon 2024, its annual high mass

Video games: Blizzard cancels Blizzcon 2024, its annual high mass Falling wings of the Moulin Rouge: who will pay for the repairs?

Falling wings of the Moulin Rouge: who will pay for the repairs? “You don’t sell a company like that”: Roland Lescure “annoyed” by the prospect of a sale of Biogaran

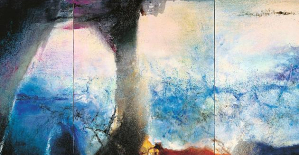

“You don’t sell a company like that”: Roland Lescure “annoyed” by the prospect of a sale of Biogaran Exhibition: in Deauville, Zao Wou-Ki, beauty in all things

Exhibition: in Deauville, Zao Wou-Ki, beauty in all things Dak’art, the most important biennial of African art, postponed due to lack of funding

Dak’art, the most important biennial of African art, postponed due to lack of funding In Deadpool and Wolverine, Ryan and Hugh Jackman explore the depths of the Marvel multiverse

In Deadpool and Wolverine, Ryan and Hugh Jackman explore the depths of the Marvel multiverse Tom Cruise returns to Paris for the filming of Mission Impossible 8

Tom Cruise returns to Paris for the filming of Mission Impossible 8 Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Euroleague: at the end of the suspense, Monaco equalizes against Fenerbahçe

Euroleague: at the end of the suspense, Monaco equalizes against Fenerbahçe Women's Six Nations: Where to see and five things to know about France-England

Women's Six Nations: Where to see and five things to know about France-England Liverpool: it is confirmed, Slot will succeed Klopp on the Reds bench

Liverpool: it is confirmed, Slot will succeed Klopp on the Reds bench Ligue 1: Montpellier and Nantes back to back, two reds in stoppage time

Ligue 1: Montpellier and Nantes back to back, two reds in stoppage time