For its very last screening, Brittany screened The Marvels on Tuesday, November 14 at 8:30 p.m. in front of... three spectators. Its closure took place with the greatest discretion. It was while buying the small magazine L’Officiel des Spectacles from his newsagent that Axel Huyghe, head of the site sallecinéma.com, discovered it. “Under the name of the cinema in the program pages, it just said ‘permanent closure’,” he explains. For this specialist in cinemas and author of a reference book on this cinema (*), a page is turning. “I went this summer to Brittany to see the latest Mission: Impossible with Tom Cruise and the room was clearly out of breath, particularly in its sets,” he remembers.

Having died last May, Benjamine Rytmann-Radwanski (1928-2023) will not have seen her beloved cinema close its doors. At the end of 2009, it sold all its cinemas, including the Bretagne at 73 boulevard du Montparnasse in the 6th arrondissement of Paris to Jérôme Seydoux, owner of the Pathé group. Despite her age, this very authoritarian little lady remained at the head of this rental-managed room until Covid. Tired by the pandemic, she returned the keys to Pathé when the cinemas reopened. Since then, Pathé has operated it with difficulty because people simply no longer go there. “In 2023, 20,000 spectators pushed open the door of Bretagne compared to a total of 700,000 expected in 2023 for our three other cinemas right next door: the PathéParnasse, the Miramar and the Montparnos”, explains to Figaro Aurélien Bosc President of Pathé Cinémas. These attendance figures explain our choice to transfer the activity of Bretagne to our other nearby venues.” And to clarify: “Contrary to rumors, the Miramar is not on reprieve and it remains in operation.”

What will become of Brittany? “It is still the property of Pathé,” explains Aurélien Bosc. We studied the possibility of converting it into a theater but this is impossible because there is not enough space to create dressing rooms and storage areas for the sets. We are not going to turn it into a cinema because the neighborhood already has a lot of them. We will study other possibilities, in discussion with the co-ownership and the city of Paris.”

The Bretagne saga is not trivial. It all starts in what is now Belarus. Fleeing the pogroms, the Ashkenazi Jew Joseph Rytmann (1903-1983) settled in Paris. He worked in wood and textile stores before focusing on cinemas. “Before the war, cinemas were a flourishing business,” says his biographer Axel Huyghe. In 1933, Joseph Rytmann began by purchasing the Miramar in Alésia which, after having been the Montrouge theater, had already been transformed into a cinema. In 1938, he acquired the Miramar in Montparnasse. During the Occupation, French Jews of the Jewish faith were prohibited from operating theaters and cinemas. Joseph Rytmann is spoiled and takes refuge in the free zone. He survived the war and had to fight in court at the Liberation to get his cinemas back. He succeeds and builds a small empire which includes Montparnos, Bienvenue, Bretagne... The latter is so named because it is located in the stronghold of the Bretons, a district full of creperies because the Montparnasse station directly serves the country of Breizh.

Le Bretagne was inaugurated with great fanfare on September 27, 1961 with Le cave se rebiffe by Gilles Grangier with Jean Gabin, Martine Carole, Bernard Blier. It is the third largest room in the capital (850 seats) after the Grand Rex and the UGC Normandie. A second room was dug there in 1973. Among the operators, Joseph Rytmann is known for his bad temper and his Russian accent but he is very respected. Nicknamed “the Emperor of Montparnasse”, it was he who made Montparnasse the essential area for screening new films in the capital after the Champs-Élysées and the Grands Boulevards which are located on the right bank of the Seine. “The Bretagne was what we called in the jargon, an exclusive cinema, it only showed new films. At the time, it was rare. There were the exclusive theaters, then those who did the second exclusivity before the general release,” says Axel Huyghe. Joseph Rytmann worked until his death in 1983. His daughter succeeded him. At the end of 2009, she handed over the family circuit to Pathé. In 2012, Bienvenüe-Montparnasse became Jean-Marc Dumontet's Grand Point-Virgule theater. Miramar is annexed to Gaumont Parnasse. The Mistral, near Alésia, closed in 2016. Spectators now go directly opposite the very modern Pathé Alésia. Until the end, Bretagne will have kept the Rytmann name on its facade...

(* Rytmann, the adventure of a cinema operator in Montparnasse, Axel Huyghe and Arnaud Chapuy, preface by Claude Lelouch. L’Harmattan, 128 pages, 30 euros.

(** https://salles-cinema.com/paris/cinema-le-bretagne-a-paris)

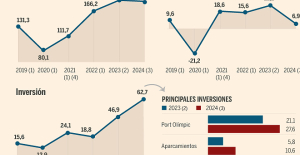

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives

War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

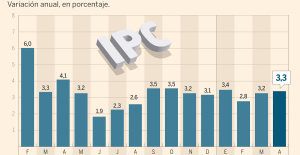

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” Inflation rises to 3.3% in April and core inflation moderates to 2.9%

Inflation rises to 3.3% in April and core inflation moderates to 2.9% Pedro Sánchez announces that he continues "with more strength" as president of the Government

Pedro Sánchez announces that he continues "with more strength" as president of the Government Irritable bowel syndrome: the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets is confirmed

Irritable bowel syndrome: the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets is confirmed Beware of the three main sources of poisoning in children

Beware of the three main sources of poisoning in children Relief at Bercy: Moody’s does not sanction France

Relief at Bercy: Moody’s does not sanction France More than 10 million holders, 100 billion euros: the Retirement Savings Plan is a hit

More than 10 million holders, 100 billion euros: the Retirement Savings Plan is a hit Paris 2024 Olympic Games: the extension of line 14 will open “at the end of June”, confirms Valérie Pécresse

Paris 2024 Olympic Games: the extension of line 14 will open “at the end of June”, confirms Valérie Pécresse Failing ventilators: Philips to pay $1.1 billion after complaints in the United States

Failing ventilators: Philips to pay $1.1 billion after complaints in the United States The Cannes Film Festival welcomes Omar Sy, Eva Green and Kore-Eda to its jury

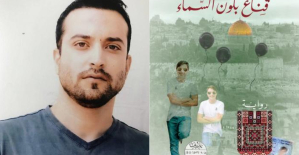

The Cannes Film Festival welcomes Omar Sy, Eva Green and Kore-Eda to its jury Prisoner in Israel, a Palestinian receives the International Prize for Arab Fiction

Prisoner in Israel, a Palestinian receives the International Prize for Arab Fiction Harvey Weinstein, the former American producer hospitalized in New York

Harvey Weinstein, the former American producer hospitalized in New York New success for Zendaya, tops the North American box office with Challengers

New success for Zendaya, tops the North American box office with Challengers Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Europeans: a senior official on the National Rally list

Europeans: a senior official on the National Rally list Blockade of Sciences Po: the right denounces a “drift”, the government charges the rebels

Blockade of Sciences Po: the right denounces a “drift”, the government charges the rebels Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar NBA: young Thunder coach Mark Daigneault named coach of the year

NBA: young Thunder coach Mark Daigneault named coach of the year Athletics: Noah Lyles in legs in Bermuda

Athletics: Noah Lyles in legs in Bermuda Serie A: Dumfries celebrates Inter Milan title with humiliating sign towards Hernandez

Serie A: Dumfries celebrates Inter Milan title with humiliating sign towards Hernandez Tennis: no pity for Sorribes, Swiatek is in the quarterfinals in Madrid

Tennis: no pity for Sorribes, Swiatek is in the quarterfinals in Madrid