After having remained silent for decades about its slave trading past, Bordeaux is seeking to catch up on the thorny question of the duty of remembrance, far from being obvious between the municipality, historians and an association which is strained by its activism. More than 30 years after Nantes, which examined its responsibility in the history of the French slave trade and triangular trade in 1992, Bordeaux is still trying to get rid of accusations of “softness” concerning it.

“There is change, in particular thanks to the massive arrival of Neo-Bordelais in recent years, less dependent on family taboos,” estimates Karfa Diallo, director and founder of the Mémoires et Partages association. For this Franco-Senegalese activist who took up the issue at the end of the 1990s, it is “Bordeaux society” which is moving the lines in the face of the “wait-and-see attitude” and “follow-through” of elected officials.

Some 500 slave-trading expeditions left the Gironde capital for Africa between 1672 and 1837. “Bordeaux, known worldwide thanks to wine, is a city that is proud of itself and does not like people to deal with subjects that could devalue it,” says Éric Saugéra, a Nantes historian who was the first to “light the fuse” by publishing the book “Bordeaux slave port” in 1995.

It was not until 2009 that the Aquitaine Museum in Bordeaux dedicated rooms to Atlantic trade in the 18th century and the slave trade, on the recommendations of a reflection committee initiated by the town hall. And 2019 for the inauguration on the banks of the Garonne of a statue of Modeste Testas, an African slave deported to Santo Domingo and bought by people from Bordeaux then freed.

Several streets bearing the name of Bordeaux slave traders were also equipped with explanatory plaques after the death of George Floyd in the United States and the movement to remove statues linked to slavery. Initiatives, driven by the former right-wing municipality, appreciated but “insufficient”, according to Karfa Diallo, for whom the environmentalist town hall “has not overturned the table” on this subject since its election in 2020.

Karfa Diallo organizes guided tours in Bordeaux following the traces of trafficking. He campaigns for the creation of a “Slavery and Resistance House”. His association set up a steering committee at the end of January for the creation of this “dynamic place for the exchange of ideas, a space for debate, conferences and contemplation” but without the representation of local communities.

“We have no brakes on addressing this issue. The challenge for us is to succeed in finding the point of balance between a story which is based on historical facts, without falling into a militant story,” squeaks Baptiste Morin, municipal councilor in charge of heritage. . The environmentalist municipality - which notably added to the first plaques a mention of the so-called Taubira law recognizing trafficking as a crime against humanity - wishes to install five new ones. This story also arouses tension among certain descendants of slave shipowners, “very worried about how we might perceive their family today,” points out Mr. Morin.

“The Bordeaux merchant elites took full advantage of the slave system and were enriched by it,” underlines the mayor of Bordeaux Pierre Hurmic, while insisting on his desire to “build consensus, to bring together” in his memory policy, which also concerns the Shoah. “We have nothing to be ashamed of what we are doing here in Bordeaux, even if we started later than Nantes. We are trying to catch up,” he pleads. But for Bordeaux historian Caroline Le Mao, “working on memory without working on historical content becomes meaningless.”

This researcher, who regrets that historians are not sufficiently associated with the initiatives of the City or the Mémoires et Partages association, supports memory work aimed at the “enslaved”. “To repair is also to give life back to these people” so as not to be “just numbers,” she says.

In this vein, the town hall wishes to create in the coming years a memorial dedicated to the victims of trafficking and slavery. The Bordeaux expeditions alone led to the deportation of between 120,000 and 150,000 blacks.

What is chloropicrin, the chemical agent that Washington accuses Moscow of using in Ukraine?

What is chloropicrin, the chemical agent that Washington accuses Moscow of using in Ukraine? Poland, big winner of European enlargement

Poland, big winner of European enlargement In Israel, step-by-step negotiations for a ceasefire in the Gaza Strip

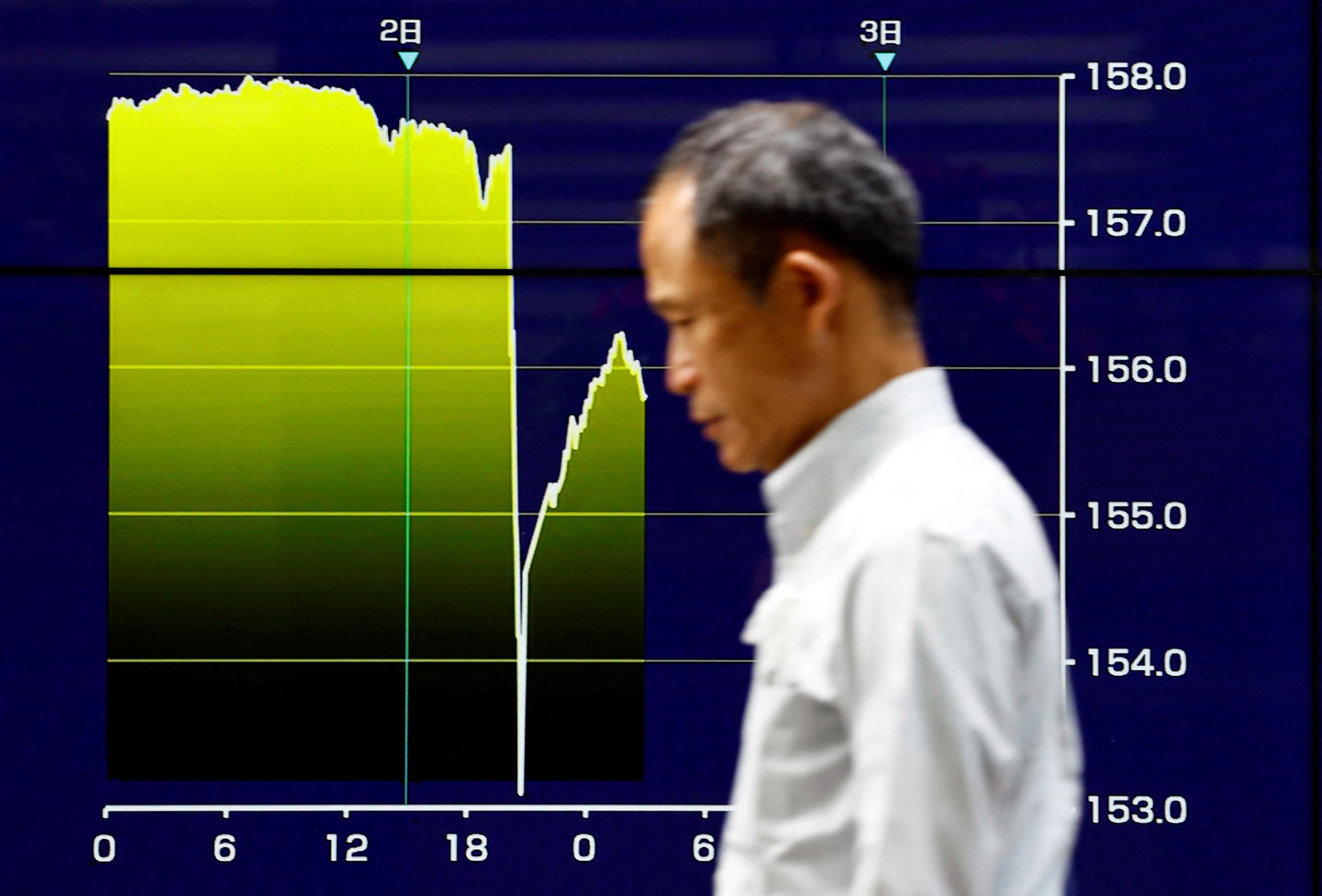

In Israel, step-by-step negotiations for a ceasefire in the Gaza Strip BBVA ADRs fall almost 2% on Wall Street

BBVA ADRs fall almost 2% on Wall Street Breast cancer: less than one in two French women follow screening recommendations

Breast cancer: less than one in two French women follow screening recommendations “Dazzling” symptoms, 5,000 deaths per year, non-existent vaccine... What is Lassa fever, a case of which has been identified in Île-de-France?

“Dazzling” symptoms, 5,000 deaths per year, non-existent vaccine... What is Lassa fever, a case of which has been identified in Île-de-France? Sánchez cancels his agenda and considers resigning: "I need to stop and reflect"

Sánchez cancels his agenda and considers resigning: "I need to stop and reflect" The Federal Committee of the PSOE interrupts the event to take to the streets with the militants

The Federal Committee of the PSOE interrupts the event to take to the streets with the militants Volvic factory shut down after “an act of malicious intent”: production can resume “at the earliest” on Friday

Volvic factory shut down after “an act of malicious intent”: production can resume “at the earliest” on Friday SNCF: algorithmic video surveillance in stations attacked before the CNIL

SNCF: algorithmic video surveillance in stations attacked before the CNIL Europeans: Macron's speech at the Sorbonne counted as speaking time on the Renaissance list

Europeans: Macron's speech at the Sorbonne counted as speaking time on the Renaissance list The government wants to strengthen its controls on cryptocurrency holders

The government wants to strengthen its controls on cryptocurrency holders Jean Reno publishes his first novel Emma on May 16

Jean Reno publishes his first novel Emma on May 16 Cannes Film Festival: Meryl Streep awarded an honorary Palme d’Or

Cannes Film Festival: Meryl Streep awarded an honorary Palme d’Or With A Little Something Extra, Artus and his disabled actors do better than Intouchable on the first day

With A Little Something Extra, Artus and his disabled actors do better than Intouchable on the first day Madonna ends her world tour with a giant - and free - concert in Copacabana

Madonna ends her world tour with a giant - and free - concert in Copacabana Omoda 7, another Chinese car that could be manufactured in Spain

Omoda 7, another Chinese car that could be manufactured in Spain BYD chooses CA Auto Bank as financial partner in Spain

BYD chooses CA Auto Bank as financial partner in Spain Tesla and Baidu sign key agreement to boost development of autonomous driving

Tesla and Baidu sign key agreement to boost development of autonomous driving Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV The home mortgage firm rises 3.8% in February and the average interest moderates to 3.33%

The home mortgage firm rises 3.8% in February and the average interest moderates to 3.33% This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Europeans: a senior official on the National Rally list

Europeans: a senior official on the National Rally list Blockade of Sciences Po: the right denounces a “drift”, the government charges the rebels

Blockade of Sciences Po: the right denounces a “drift”, the government charges the rebels Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar OM-Atalanta: the lines of the match

OM-Atalanta: the lines of the match Ligue 1: Lorient supporters invade the training center

Ligue 1: Lorient supporters invade the training center Hand: Montpellier overthrown by Kiel in the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier overthrown by Kiel in the Champions League Tennis: Medvedev gives up, Lehecka in semi-finals

Tennis: Medvedev gives up, Lehecka in semi-finals