Mata Hari, Mata Hari again and again: it seems to be the only name that most people can still think of when it comes to female espionage. Dozens of films have been made about the Dutch woman, and 250 books have been written about this eccentric dancer because she so perfectly corresponded to the cliché of sex, power and mystery.

But who knows Elisabeth Schragmüller? It is to the credit of the author duo Maik Baumgärtner and Ann-Katrin Müller that their new book "The Invisibles: How Female Secret Agents Shaped German History" sheds a lot of light into the darkness of the history of female espionage over the past 100 years. To do this, they went to numerous archives, viewed endless documents, but also tried to get in touch with today's services.

But back to Elisabeth "Elsbeth" Schragmüller: She was something like Mata Hari's "command officer", who was rudely called "H 21" by the Germans. Schragmüller, one of the first women with a doctorate in Germany, operated from Brussels as head of the German espionage department against France in the Supreme Army Command and taught Mata Hari, among other things, how to write with “secret ink”. At the end of the 1920s she was supposed to write a book about espionage and advocate the thesis that “the emotional predisposition, which is stronger than that of men,” predestines women for the intelligence services.

The espionage of the victorious powers of the First World War was primarily aimed at Germany in order to check the political situation in the defeated country and whether the Treaty of Versailles, which prohibited rearmament, was being observed. One of the agents was Alwine Brusis, who worked for the French. She had gallant conversations with officers in Düsseldorf cafés. She found material and lists of names about the activities of banned "resident militias" such as Orsch or Orka and recruited new spies. By the time Alwine Brusis was found out and convicted, she had received between 3,500 and 4,500 marks a month (the average monthly income at the time was 179 marks). Brusis got out of prison during the Nazi era and fell into the clutches of the Gestapo. She died exhausted in 1941.

It was maids, milliners or saleswomen who approached officers "out of lack of money, a thirst for adventure or because they reject German politics". Their names were Bertha, Frieda, Margarete or Paula. They worked as couriers, attended events and made reports. "Treason to the fatherland by women" particularly shocked the judges at the time. And yet the fictionalization of woman as a mysterious, strong subject in the cinema was already beginning: one remembers silent films such as "Spione" by Thea von Harbou (Fritz Lang's wife; 1928), Greta Garbo in "Der Krieg im Dunkel" by 1928, in which she plays a Russian spy. Or "Dishonoured" with Marlene Dietrich as the spy "X 27" from 1931.

The disregard that the brown masters showed women opened up these spaces. Nathalie Sergueiev, a Russian who grew up in Paris, spied for the English in Madrid in 1943 against German military intelligence. She was the best-known double agent of World War II. An adventuress who rode her bike from Paris to Beirut. As a very young woman she had walked from Paris to Warsaw and written about it. She got to know Nazi greats like Hermann Göring and Franz von Papen, who amazingly trusted her.

Nathalie Sergueiew took a German radio with her to London, which she used to feed false information to the Wehrmacht. In the end, she was partly responsible for the success of D-Day on June 6, 1944, by attracting the attention of the Germans away from Normandy to the Pas de Calais with her radio signals. "You have landed," wrote the woman with kidney disease happily that day.

There were other D-Day women: they derailed trains, blew up weapons caches, destroyed telephone and power lines. All this was the task of a British special unit behind the German front. A total of 39 women jumped off with parachutes. Half were caught and a third died in action.

Virginia Hall, the top American agent in France, who also failed to get hold of Klaus Barbie, the feared Gestapo chief in Lyon, is considered the "most wanted spy of the Second World War". She worked in consulates, accidentally shot herself in the leg while hunting, and was amputated below the knee. She worked for the British SOE (Special Operations Executive) with the "license to kill" as we know it from 007 films. She disguised herself as a journalist in France and Spain, helped the underground with weapons, and blew up bridges. In 1944 she switched to the US Army service OSS (Office of Strategic Services) and prepared the Allied landings on the Côte d'Azur in August 1944. After the war, she was the only female agent to be officially honored.

Virginia Hall's example led to a riot in US intelligence in 1953. A top agent like her earned less than male colleagues. As early as 1953, women rebelled against their unequal treatment and managed to set up a committee, condescendingly called the "Pettycoat" committee. He didn't do much.

During the Cold War, the Soviet KGB and East German state security were the West's most vigorous opponents. The Federal Intelligence Service (BND), the Office for the Protection of the Constitution and the Military Counterintelligence Service emerged in the Federal Republic.

“The Cold War is characterized by covert actions, sabotage, attacks and murders. In addition, the era of defectors and agents begins,” write Baumgärtner and Müller. And they devote themselves first and foremost to those women who successfully spied for the West, such as Erika Lokenvitz, who was a CIA spy in the East for twelve years before she was arrested in 1966 and taken to the Stasi Bautzen II prison. Lokenvitz worked with a friend, Gertrude Liebing, who was ten years his senior. She delivered material to West Berlin, but her messages were decrypted. She was sentenced to six years in prison, but died six weeks later.

The women often worked as secretaries in ministries, like Elli Barczatis with East German Prime Minister Otto Grotewohl. It was led by BND boss Reinhard Gehlen, and its operation was called "Daisy". In 1955 she was exposed and sentenced to death by a blade ax for betraying state secrets. Because she worked on the "Adenauer propaganda machine".

In the age of “spying secretaries”, the “Lenchen” led by the BND met the then wife of KGB agent Vladimir Putin, Lyudmila, in Dresden headquarters. The term "secretary" is condescending. Today one would speak of office management or assistant. Lyudmila told Lenchen that her husband was cheating on her and hitting her. At least that's what it says in the files of the BND. Today's Russian President and warmonger Vladimir Putin was stationed in Dresden from 1985 to 1990 for the Soviet intelligence service, worked in political reconnaissance, and said he collected information about politicians and the plans of potential enemies there.

And in the west? One of the most important Stasi informants about the CDU, Christel Broszey, sat in the office of CDU man Kurt Biedenkopf. Her case did not cause such a stir as that of Günter Guillaume, whose exposure in 1974 led to Chancellor Willy Brandt's resignation. The GDR leadership later honored Broszey as an "ambassador of peace". She was organizational and clever. All processes went through her desk, she had everything under control. She escaped arrest by fleeing to the GDR.

The peaceful fall of the wall provoked the vision of a world without espionage in this country. The services were reduced, the protection of the constitution concentrated on the processing of the Stasi crimes and structures, some of them still do today. 7,000 investigations were conducted, but only a few hundred people were convicted. But even after the end of the USSR, the Federal Republic remained in the sights of Russia or China.

In 2011, a couple was arrested by a GSG9 commando. It was the first exposure of agents after the Cold War - and a shock to German politics and the public. The couple, who called themselves "Anschlag" and had been provided with a clever legend by the Russian side, had managed to work in Germany for Moscow services for 20 years. They spied on a Dutch official who had access to NATO and EU documents, which are too lax on the western side. It was particularly explosive that the Russians wanted to know how Brussels thought about Ukraine.

Today, the greatest gateway is still the great naivety of the Germans, say constitutional protection officers from the federal and state governments. Organizations like the CIA or the British MI6 have never been able to hold a candle. In the meantime there have been and still are one or the other president of the Office for the Protection of the Constitution of a federal state (the non-party Beate Bube since 2008 in Baden-Württemberg, Martina Rose has headed the MAD since 2020), but the offices are still too one-dimensionally structured, too hermetic, complacent, hierarchical and subcomplex. Baumgärtner and Müller conclude that women are still doubly invisible in the services: because too few people still believe that women are capable of working in the secret service and because they are underestimated as perpetrators by right-wing and left-wing radicals and Islamists.

Of course, sex played a big role then as now, even if the services don't like to hear it. The Stasi spoke of the “Intimate Life Attack Front” to blackmail men with compromising material. A method that China is refining with fake digital profiles on social media. Women continue to be used as decoys, the secret service speaks of "honey traps".

In a globalized world, there are infinitely many ways in politics, business and research to overwhelm gullible minds who do not want to understand what hostile energy is actually confronting them. It would be surprising if Russia or China (or Iran or North Korea) did not continue to exploit this potential. So the methods of espionage may have changed, but Mata Hari lures forever.

Mata Hari from the Netherlands became a sex idol with her erotic dance. But she served not only male fantasies, but also the secret services in Germany and France.

What: N24

The Dutchwoman Margaretha Geertruida Zelle (1876–1917) from Leeuwarden had lived in Indonesia for some time as the wife of a colonial officer. After the divorce, she transformed into the artificial figure of an Indian dancer (Mata Hari = sun), whose central message was a sultry, overwhelming eroticism. This made her a star of the bourgeoisie and bohemian, rich admirers on stage and in bed.

Since the selection dwindled after the outbreak of the First World War, she allowed herself to be recruited as a spy by the German military intelligence service in 1915 for a lavish fee. She also accepted an offer from the French Deuxième Bureau. In 1917, services of the Entente set a trap for the double agent in Paris. Although it was clear to the military judges that she had revealed nothing of real relevance, she was shot in Vincennes.

Maik Baumgärtner and Ann-Katrin Müller: "The Invisibles: How Secret Agents Shaped German History". (DVA, Munich. 377 p., 24 euros)

You can also find "World History" on Facebook. We are happy about a like.

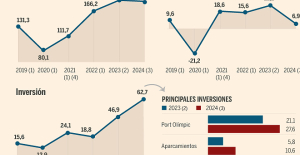

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives

War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte

First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025

Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025 Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Inflation rebounds in March in the United States, a few days before the Fed meeting

Inflation rebounds in March in the United States, a few days before the Fed meeting Video games: Blizzard cancels Blizzcon 2024, its annual high mass

Video games: Blizzard cancels Blizzcon 2024, its annual high mass Falling wings of the Moulin Rouge: who will pay for the repairs?

Falling wings of the Moulin Rouge: who will pay for the repairs? “You don’t sell a company like that”: Roland Lescure “annoyed” by the prospect of a sale of Biogaran

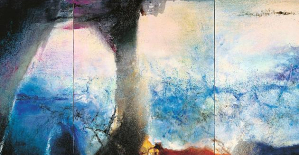

“You don’t sell a company like that”: Roland Lescure “annoyed” by the prospect of a sale of Biogaran Exhibition: in Deauville, Zao Wou-Ki, beauty in all things

Exhibition: in Deauville, Zao Wou-Ki, beauty in all things Dak’art, the most important biennial of African art, postponed due to lack of funding

Dak’art, the most important biennial of African art, postponed due to lack of funding In Deadpool and Wolverine, Ryan and Hugh Jackman explore the depths of the Marvel multiverse

In Deadpool and Wolverine, Ryan and Hugh Jackman explore the depths of the Marvel multiverse Tom Cruise returns to Paris for the filming of Mission Impossible 8

Tom Cruise returns to Paris for the filming of Mission Impossible 8 Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Euroleague: at the end of the suspense, Monaco equalizes against Fenerbahçe

Euroleague: at the end of the suspense, Monaco equalizes against Fenerbahçe Women's Six Nations: Where to see and five things to know about France-England

Women's Six Nations: Where to see and five things to know about France-England Liverpool: it is confirmed, Slot will succeed Klopp on the Reds bench

Liverpool: it is confirmed, Slot will succeed Klopp on the Reds bench Ligue 1: Montpellier and Nantes back to back, two reds in stoppage time

Ligue 1: Montpellier and Nantes back to back, two reds in stoppage time