The creator of the film was known for always pointing out grievances despite all the slapstick comedy. He demonstrated this in his film “Modern Times” as an example, in which a factory worker can no longer turn off the hand movement that he has to do all day long on the assembly line after work. But on October 15, 1940, it was no longer about the hardships of a market economy that degraded people to living machines. That day was about much more for Charlie Chaplin and for the whole world.

"The Great Dictator" was the name of the work that was released in cinemas in the United States - and anyone who didn't walk through the world with their eyes closed and ears covered also knew on the other side of the Atlantic: The comedian had planned nothing less than a satire on Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist power elite; i.e. those misanthropes who first turned Germany into a terrorist state, then started a war in Europe with the attack on Poland and now, after subjugating France, were at the peak of their power.

The sheer size of this project still amazes after decades. To take such a sensitive political issue as an entertainer and add a humorous side to it while people are dying or being humiliated en masse, requires the utmost self-confidence. At the time of the premiere, the USA was not yet at war with the Nazi Reich. President Franklin D. Roosevelt knew only too well what a powerful lobby the descendants of millions of German immigrants formed - and he himself had to contend with the pervasive racism in his own country.

But no matter how great the pressure on Chaplin, he found a solution to almost every pitfall. Even the idea of the story turned out to be brilliant: it tells the story of a poor Jewish hairdresser who went into battle in World War I for the fantasy state of Tomania, which everyone equated with Germany. Twenty years later, under the symbol of the double cross, the dictator Anton Hynkel rules there, who looks confusingly similar to the hairdresser. Surrounded by his camarilla Dr. Gorbitsch (Joseph Goebbels) and Field Marshal Hering (Hermann Göring), Hynkel dreams of conquering the world.

After initial quarrels, Benzino Napoloni (Benito Mussolini) also fights as a friend of the autocrat during a state visit at Hynkel's side, so that nothing should actually stand in the way of the campaign of all campaigns. But on the day of a big speech, there is a confusion: it is not Hynkel who comes to the desk, but his henchmen who think the hairdresser from the ghetto is their leader, put him in the appropriate uniform and urge him to give the speech.

Chaplin seems to have known to rely on the punch line that in reality there was a physical resemblance between him and Hitler. The comedian was said to be angry that the tyrant also appeared with a trimmed mustache, which Chaplin perceived as theft. Turning into his enemy on screen, imitating his gestures in such a way that their ridiculousness came across, or delivering speeches in imaginative language that at times bordered on animal grunts (“Rasdwa – Drisdwa!”), Chaplin must do a great job have given pleasure.

Attentive viewers will also have noticed how mindless things are in Hynkel's court. Field Marshal Hering always bugged his boss with a jovial smile and sentences like "We have discovered the best poison gas of all time". Gorbitsch creeps through the plot as a boss dislike, as if every upright walk was alien to him, because it wasn't the last one something as absurd as one's own views.

The scene in which Napoloni munches while watching a military parade and asks why the tanks in Tomania didn't have headlights for underwater travel, as he did, is particularly significant. Gorbitsch quickly has to explain that this technology is long outdated, because dictators and their henchmen are not allowed to admit weaknesses at any price. What Hannah Arendt would later call the “banality of evil” is probably already present in all of this.

These sequences were topped by Hynkel's dance around the globe until it bursts like the dream of world domination. Critics have wanted to discover an inadmissible aestheticization in it, but the whole hopelessness of Hitler's plans has probably become clear to more viewers from the scene. Incidentally, it is not clear whether the real dictator ever saw the film: it is certain that the Nazis had two copies obtained and wanted to show the work to their Führer; but whether it came to that, the documents do not say.

Last but not least, the speech that the poor hairdresser gives in place of Hynkel in the film speaks against a personal view of Hitler. It stands in such contradiction to everything that the National Socialists disseminated that the probability of Adolf Hitler having a fit of rage, which is worthy of tradition, was almost 100 percent. Chaplin's facial expression alone speaks volumes: this man does not want to oppress anyone, does not want to degrade anyone, and last but not least he believes brute force is a solution.

The words he speaks fit this: Here someone is talking about freedom and humanity, about the fact that there is enough for everyone on earth that science can bring progress, in short: about a great togetherness in freedom. The direct appeal to the soldiers to ask what they are fighting for may seem naïve - but what else can you say to people in uniform who are said to have the ability to think? Yes, Charlie Chaplin painted a dream world here that would have required a humanity without black parts in the soul, and yet everything else in 1940 would have been too little.

In the US, audiences and critics alike celebrated the film: "Truly an outstanding work by a truly great artist and - from a certain point of view - perhaps the most important film ever made," judged the "New York Times". Only one scene in the fictional concentration camp was too close to slapstick for the majority - something for which Chaplin immediately apologized. At the Oscars, The Great Dictator was nominated in five categories, but received no award. Film historians are still puzzled today as to how this could have happened.

After May 8, 1945, the Western Allies were at odds as to how quickly the Germans could be expected to do the work. In August 1946, they showed the film twice in a row in a West Berlin cinema to an audience that had actually come for Miss Kitty. The reactions were enlightening: Laughter erupted above all in scenes with Field Marshal Hering, which suggests that his role model Herrman Göring as a happy fat man must have been quite popular with the people.

But of course there was also dismay and anger: as a foreigner, Charlie Chaplin already knew in 1940 how inhuman National Socialism was. This was at the expense of the German interpretation of having been Hitler's first victim and otherwise not having known anything. Many viewers could not forgive the comedian. What Chaplin was comfortable with: he might not have defeated the man who once stole his beard. He had always presented it completely. Without a doubt, this represents an achievement that has remained unique to this day.

You can also find "World History" on Facebook. We are happy about a like.

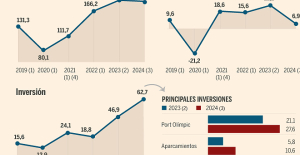

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives

War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte

First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025

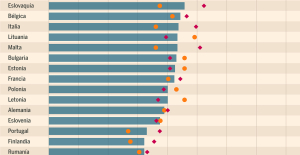

Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025 Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Inflation rebounds in March in the United States, a few days before the Fed meeting

Inflation rebounds in March in the United States, a few days before the Fed meeting Video games: Blizzard cancels Blizzcon 2024, its annual high mass

Video games: Blizzard cancels Blizzcon 2024, its annual high mass Falling wings of the Moulin Rouge: who will pay for the repairs?

Falling wings of the Moulin Rouge: who will pay for the repairs? “You don’t sell a company like that”: Roland Lescure “annoyed” by the prospect of a sale of Biogaran

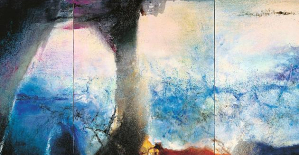

“You don’t sell a company like that”: Roland Lescure “annoyed” by the prospect of a sale of Biogaran Exhibition: in Deauville, Zao Wou-Ki, beauty in all things

Exhibition: in Deauville, Zao Wou-Ki, beauty in all things Dak’art, the most important biennial of African art, postponed due to lack of funding

Dak’art, the most important biennial of African art, postponed due to lack of funding In Deadpool and Wolverine, Ryan and Hugh Jackman explore the depths of the Marvel multiverse

In Deadpool and Wolverine, Ryan and Hugh Jackman explore the depths of the Marvel multiverse Tom Cruise returns to Paris for the filming of Mission Impossible 8

Tom Cruise returns to Paris for the filming of Mission Impossible 8 Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Euroleague: at the end of the suspense, Monaco equalizes against Fenerbahçe

Euroleague: at the end of the suspense, Monaco equalizes against Fenerbahçe Women's Six Nations: Where to see and five things to know about France-England

Women's Six Nations: Where to see and five things to know about France-England Liverpool: it is confirmed, Slot will succeed Klopp on the Reds bench

Liverpool: it is confirmed, Slot will succeed Klopp on the Reds bench Ligue 1: Montpellier and Nantes back to back, two reds in stoppage time

Ligue 1: Montpellier and Nantes back to back, two reds in stoppage time