When the Japanese declaration of war was received in St. Petersburg in February 1904, the case was clear to the Russian public. There was talk of a crusade against the “impudent Mongol hordes”. The Japanese were depicted as little slit-eyed monkeys with yellow skin fleeing in panic from the huge white fist of a burly Russian soldier. And Minister of War Alexei Kuropatkin (1848–1925) declared that he only needed two Russian soldiers against three Japanese ones to deal with the enemy. He soon had the opportunity to prove this, since he was appointed supreme commander of the Tsarist armies in the Far East.

Kuropatkin was considered a specialist in oriental affairs. Since his training in the cadet corps, he had repeatedly taken on military and political missions in Central Asia and had been instrumental in the conquest of the region by Russian troops. In addition, entrusted with high posts in the General Staff, he was appointed Minister of War in 1898. For him, Japan was something similar to the various emirates that had hitherto overrun the armies of the tsar.

However, that was a fallacy. Since the opening of the shogunate regime, which had been isolated for centuries, by American ships in 1853, the German Empire had experienced rapid modernization based on the Western model. China was the first to experience this, suffering a heavy defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894/95). In the Peace of Shimonoseki, however, Russia prevented the cession of the Liaodong Peninsula (southwest of Korea) and occupied the strategically important region with the ice-free port of Port Arthur itself. In the course of the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1900, parts of Manchuria and Korea were added.

When Japan demanded a withdrawal from Korea, the Tsarist Empire refused. As a result, Japan opened the war and eliminated the Russian Far East Fleet with quick strikes. Soon after, the Tenno's troops broke through the Russian lines at the Yalu River border and advanced into the Liaodong Peninsula. There, too, the Tsar's soldiers were defeated, so that their opponents could begin the siege of Port Arthur.

The defeats made it clear that the tsarist governor of the Far East, Yevgeny Alexeyev, and other warmongers had based their calculations on completely false assumptions. The Japanese were not timid fighters, nor did they have modern weapons and prudent strategists. Instead, it turned out that supplies for their own armies could not be guaranteed via the single-track Trans-Siberian Railway. It took up to 50 days to transport a regiment over the 6000 km route. There was far too little artillery. And the antiquated doctrine of being able to compensate with dashing bayonet charges bordered on suicide in the face of Japanese guns.

Admiral Alexeyev stood for the incompetence of the Russian leadership. With limited resources, he forced Kuropatkin to adopt an offensive strategy against a numerically superior opponent. This meant that in October 1904 the General had to advance on Port Arthur with his half-armed troops to break the siege ring. Because the Russian Baltic Fleet, which had also been sent on a march halfway around the world to reinforce it, would arrive too late.

The Japanese were able to fend off the Russian advance, which cost Alexeyev the post. Kuropatkin became his successor. He withdrew his armies and waited for better weather. However, he soon found out that he was no longer fighting in a distant colonial war, but that he held the fate of the Tsarist Empire in his hands.

Because on January 2, 1905, Port Arthur surrendered. The news of the defeat, combined with severe supply crises, triggered riots in St. Petersburg and other cities, which culminated in “Bloody Sunday” on January 22 (Gregorian calendar), when Tsar Nicholas II’s guard troops rioted in front of the Winter Palace fired into protesters. But the situation remained tense. Each subsequent defeat in the war could be the spark that started a revolution.

Kuropatkin therefore knew what was at stake when in February he concentrated his forces, now three armies, in a defensive position near the Manchurian city of Mukden (now Shenyang), the capital of the Liaodong Peninsula. With around 340,000 troops versus 280,000 Japanese under Field Marshal Oyama Iwao, he felt reasonably safe, especially as he held back a strong reserve in the centre. But his troops were spread across a front of up to 140 kilometers, making rapid redeployment difficult.

On the other hand, in the biggest battle since the Battle of Leipzig in 1813, Oyama Iwao relied on focus and a feint. On February 20, his right wing launched a mock attack on Kuropatkin's eastern flank. He convinced the Russians that the bulk of the enemy troops would be advancing over the mountains to the east. Only days later did it become clear that the actual attack was taking place in the west.

Because there was a danger that the Japanese would bypass the Russian lines, Kuropatkin withdrew his front behind the Han. In doing so, however, the Russians fell into disarray while their opponents advanced across the icy river. The Tsar's commanders failed to pull back their disorganized units in a coordinated manner. The Japanese advanced into the gaps, so that the operation ended in a wild flight. Large parts of the equipment were lost. At Mukden railway station, generals vented their frustration with fists.

The tsar dismissed Kuropatkin, but that did not calm the tide of domestic politics. And it got even worse. In May 1905 the Baltic fleet was almost completely sunk by the Japanese at Tsushima. For the first time in generations, a major European power had accepted defeat by an Asian state in a major war. In the Peace of Portsmouth, the tsar had to recognize the Japanese position in Korea and cede the Liaodong Peninsula with Port Arthur and the south of the Sakhalin Peninsula.

Inside, on the other hand, the revolution was raging. Mass strikes, peasant unrest and national uprisings in the multi-ethnic empire shook the autocratic regime. To save his throne, Nicholas II had to deign to grant a constitution, the centerpiece of which became a parliament, the State Duma. The tsar soon withdrew most of the concessions. But it became clear how unstable his rule had become.

In the German Reich, a far-reaching conclusion was drawn from Kuropatkin's defeat: "It has long been known that the Russian army had no important leaders ... On the other hand, the Russian soldier was considered one of the best in the world. His absolute obedience, his patient endurance, his calm defiance of death were recognized as invaluable qualities. Now the belief in these qualities has been severely shaken," said Chief of Staff Alfred von Schlieffen: "The East Asian War has shown that the Russian army was even less good than was generally believed, and it is .. .not better, but worse."

From this Schlieffen drew the conclusion for his planning that in a future war the French could be defeated before the Tsarist troops were even ready to attack. That would prove to be a fatal miscalculation in 1914.

You can also find "World History" on Facebook. We are happy about a like.

This article was first published in February 2022.

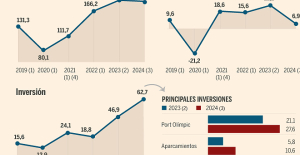

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives

War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte

First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025

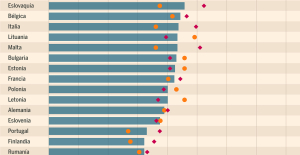

Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025 Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Inflation rebounds in March in the United States, a few days before the Fed meeting

Inflation rebounds in March in the United States, a few days before the Fed meeting Video games: Blizzard cancels Blizzcon 2024, its annual high mass

Video games: Blizzard cancels Blizzcon 2024, its annual high mass Falling wings of the Moulin Rouge: who will pay for the repairs?

Falling wings of the Moulin Rouge: who will pay for the repairs? “You don’t sell a company like that”: Roland Lescure “annoyed” by the prospect of a sale of Biogaran

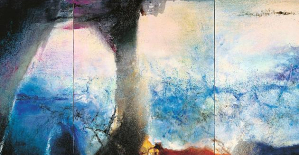

“You don’t sell a company like that”: Roland Lescure “annoyed” by the prospect of a sale of Biogaran Exhibition: in Deauville, Zao Wou-Ki, beauty in all things

Exhibition: in Deauville, Zao Wou-Ki, beauty in all things Dak’art, the most important biennial of African art, postponed due to lack of funding

Dak’art, the most important biennial of African art, postponed due to lack of funding In Deadpool and Wolverine, Ryan and Hugh Jackman explore the depths of the Marvel multiverse

In Deadpool and Wolverine, Ryan and Hugh Jackman explore the depths of the Marvel multiverse Tom Cruise returns to Paris for the filming of Mission Impossible 8

Tom Cruise returns to Paris for the filming of Mission Impossible 8 Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Euroleague: at the end of the suspense, Monaco equalizes against Fenerbahçe

Euroleague: at the end of the suspense, Monaco equalizes against Fenerbahçe Women's Six Nations: Where to see and five things to know about France-England

Women's Six Nations: Where to see and five things to know about France-England Liverpool: it is confirmed, Slot will succeed Klopp on the Reds bench

Liverpool: it is confirmed, Slot will succeed Klopp on the Reds bench Ligue 1: Montpellier and Nantes back to back, two reds in stoppage time

Ligue 1: Montpellier and Nantes back to back, two reds in stoppage time