The history of currency devaluation in Germany has a specific quality compared to other western countries. The fact that the myth of the “Golden Twenties” still lives on as a figure of speech in this country points to this peculiarity. In it, the era of the Weimar Republic is not simply nostalgically conjured up, but melancholy: as an interregnum of civil liberties, cosmopolitanism and nonchalance, as a short interim period in which the Germans became a bit American and cosmopolitan, learned to appreciate civilization instead of just culture, and went to the dance café with my darling instead of going to the restaurant with my family at the weekend.

But the danger of decadence was inscribed in the image of short-lived easygoingness. Those who live beyond their means will fall at least as low as stock prices, and those who enjoy the present too much will eventually be unable to pay off their debts. Economic crises are still interpreted with this logic in Germany today. They are not seen as a manifestation of social contradictions, but as the result of subjective misconduct. The talk of the “Golden Twenties” also follows such logic, in which the hyperinflation of 1923, the economic crisis and mass unemployment are not concealed, but are meant.

Prosperity always includes misery and splendor always includes the abyss that swallows up the revelers. The metaphor of “dance on the volcano”, which art historian Renate Berger chose in 2016 as the title for a double biography of friends Klaus Mann and Gustaf Gründgens during the Weimar Republic, who later became enemies, sums up this attitude to life. But the focus on the Weimar Republic, as characterized by the current journalistic enthusiasm for 1923 as the key year of the inflation crisis, contributes little to understanding the current mentality-historical constellation.

More revealing than the comparison itself, which is probably due to the boom in anniversaries, is the question of when the memory of the splendor and misery of the twenties is attempted. It leads back to the year 1960, not to the time of an economic crisis, but to the late phase of the so-called economic miracle. Although the inflation rate had risen for the first time after a low of just over 0.5 percent in 1959, there was little evidence of the economic upheavals that followed from 1970 onwards.

The Western Allied policy of "reeducation" was at least successful insofar as it was no longer perceived by large parts of the population as just an occupation policy, but rather as economic and social enrichment. However, this change in attitude was reflected less in a substantial Westernization of West German society than in popular culture's reconnection with the 1920s, which were perceived as the "American" decade of Germany's past.

Two events in radio history are reminiscent of this: In 1960, the Hessian Radio, moderated by Adolf Frisé, broadcast a conversation between the philosopher Theodor W. Adorno and the theater actress Lotte Lenya under the title "The Twenties - Legende and Annoyance", in which the discussants , who took part in the life of the Weimar Republic as young adults, gleefully dissected the myth of the “Golden Twenties”. In the same year, Hazy Osterwald and his jazz and swing sextet brought "Konjunktur-Cha-Cha" onto the market, which parodied the contemporary renaissance of the 1920s in a good-natured and ironic manner.

Adorno and Lenya addressed a phenomenon that Adorno took up again in his text “The Twenties”, which appeared in the magazine “Merkur” in 1962: the rumor that the twenties were the epoch of the artistic avant-garde. On the contrary, according to Adorno, the heyday of aesthetic modernism was the epoch between the fin de siècle and the First World War; Aestheticism, naturalism and expressionism lived on in the Weimar Republic as remnants of the past and culture-industrial reprises of themselves.

The New Objectivity, the main trend of the "Golden Twenties", cultivated a cold, elegant style that elevated "adjustment", anticipatory adaptation as a means of self-preservation, to a life principle. At least artistically, the Weimar Republic was more of a time when art was integrated into mass society. As a form of self-reflection, this art has produced the figure of the impostor. In her, disguise and play turned demonic.

The ambivalence of play and demonry, individual freedom and adaptation to domination, which found its concise reflection in Bertolt Brecht's "Lesbuch für Städtewohner" written between 1921 and 1928 and in Walter Serner's crime stories, shrank in the reverences that the West German culture industry denounced Twenties proved posthumously, to agreeable humor. The cynicism, conscious of its inhumanity, which Brecht made the subject of in his rules for survival for the urban isolated individual, became in Osterwald's brash indifference when it says in the "Konjunktur-Cha-Cha": "One is what one is, not through the intrinsic value. / You get that for free if you drive a road cruiser. / One does what one does only out of self-preservation. / Because you only love yourself.”

Osterwald was popular in the Federal Republic of Germany during the economic miracle because his songs were seen as a humorous tribute to the Weimar Republic. Not even obvious allusions to the National Socialist past that Osterwald made (“Get your coal / like Krupp von Bohlen / from the big world business”) were recognized as such. His song was received as an example of a harmless mixture of criticism and agreement, which already characterized many literary texts of the Weimar Republic, in which the crisis experience was only entertainingly addressed, but not reflected upon.

Thomas Mann's story Disorder and Early Suffering, published in 1925, is a prototype for depicting the subject of inflation at the time of the inflation crisis itself. Their characters – the history professor Abel Cornelius, his wife and his two children, who perceive the crisis from the perspective of their sated upper-class life – embody different ways of reacting to the new situation. The professor stands for the cheap distance of the scholar, who takes the historical constellation as an opportunity to compare earlier economic crises with the new one, and to deal with the chaos of the present with schemes from the past.

His children, on the other hand, react to the devaluation of money with experiments and with a love of risk, they “go with the economy” in order to elicit a little profit from it even when it is crashing, and come up with tricks and excuses to circumvent rationing and restrictions on access to shops. The story demonstrates that both Cornelius' experience-resistant conservatism and his children's willingness to take risks are inappropriate to reality, but ultimately remains, condensed into a prosavignette, in the scheme of the mentality novel familiar from the "Buddenbrooks", whose characters represent different mental attitudes. The aesthetic form is not changed by the new experience that it processes.

A survey of the novels of the Weimar Republic, in which the economic crisis and especially the inflation crisis is addressed - from Hans Fallada to Alfred Döblin and Vicki Baum to Irmgard Keun - would result in a tableau of social characters that, similar to Mann, are presented and exhibited, analyzed and criticized: the employee, the idler, the beggar, the entrepreneur and the crisis profiteer, who then returns to Osterwald in the late days of the economic miracle as if nothing had happened. However, the omnipresent figure of the imposter at that time, which Cornelius' children use as a guide in their picaresque efforts to obtain small pleasures, represents an attempt to reflect the crisis in an aesthetic form.

In the work of Walter Serner in particular, who published many of his texts under pseudonyms, lived in hotels under false names and adopted Brecht's maxim of covering one's own tracks in everyday practice, imposture in its ambiguity advanced to become a linguistic principle: the impostor is the one with Serner who, in the face of a crisis-ridden present and uncertain future, speculates with words like others with money, for whom every speech act is a playful pact that he enters into with the respective counterpart in order to either cheat him or the others with him to trick.

Serner perfected the transformation of language into a duel-like game in his novella Die Tigress, published in 1925 and set in a Dadaesque Paris, the story of the love of the crook Fec for the prostitute Bichette, in which love is understood as a competition who loses who is the first to fall in love "really" and not fraudulently.

Serner despised the New Objectivity as much as he fell out with the Dadaists. In his work as well as in his life, imposture finally loses its reputation as merely charming and, in the face of a historical catastrophe whose extent seemed unpredictable, proves to be a residual form of survival. In the mid-1930s, traces of Serner were lost; In 1938 he tried to emigrate to Shanghai together with his wife Dorotea; In 1942, both were murdered by the National Socialists in Latvia, presumably during deportation to Riga.

The hope preserved in his work and in his concept of the gambler that play and radical irony could offer better solutions in the face of social destruction and anarchy than bourgeois society offers them has since belonged to the past; where it lives on in an ahistorical way, as in the 1920s enthusiasm of the 1960s, its cliche is obvious. Thomas Mann wistfully evoked the gambler again and probably for the last time in his Confessions of the Imposter Felix Krull, published in 1954 but based on drafts from the 1910s. But this is another story.

In Germany, the far left wants to cap the price of “doner kebabs”

In Germany, the far left wants to cap the price of “doner kebabs” Israel-Hamas war: Gaza between hope of truce and fear of Israeli offensive in the South

Israel-Hamas war: Gaza between hope of truce and fear of Israeli offensive in the South “Mom, Dad, please don’t die”: in the United States, a nine-year-old child saves the lives of his parents injured in a tornado

“Mom, Dad, please don’t die”: in the United States, a nine-year-old child saves the lives of his parents injured in a tornado War in Ukraine: Putin orders nuclear exercises in response to Macron and “Western leaders”

War in Ukraine: Putin orders nuclear exercises in response to Macron and “Western leaders” A baby whose mother smoked during pregnancy will age more quickly

A baby whose mother smoked during pregnancy will age more quickly The euro zone economy grows in April at its best pace in almost a year but inflationary pressure increases

The euro zone economy grows in April at its best pace in almost a year but inflationary pressure increases Children born thanks to PMA do not have more cancers than others

Children born thanks to PMA do not have more cancers than others Breast cancer: less than one in two French women follow screening recommendations

Breast cancer: less than one in two French women follow screening recommendations Call for strike on Sunday at Radio France against “the repression of insolence and humor” after the suspension of Guillaume Meurice

Call for strike on Sunday at Radio France against “the repression of insolence and humor” after the suspension of Guillaume Meurice Disney: profitable streaming for the first time, after 5 years of losses

Disney: profitable streaming for the first time, after 5 years of losses “I’m going to four concerts... I spent 1,255 euros”: for Taylor Swift, these fans ready to break the bank

“I’m going to four concerts... I spent 1,255 euros”: for Taylor Swift, these fans ready to break the bank SNCF: the CEO defends the agreement on the end of career, “reasonable, balanced and useful”

SNCF: the CEO defends the agreement on the end of career, “reasonable, balanced and useful” A little something extra, signed Artus, exceeds one million entries in less than a week

A little something extra, signed Artus, exceeds one million entries in less than a week Fred Dewilde, designer and Bataclan survivor, ended his life

Fred Dewilde, designer and Bataclan survivor, ended his life “I don’t appreciate being used as media cannon fodder”: Emmanuelle Bercot responds to Isild Le Besco

“I don’t appreciate being used as media cannon fodder”: Emmanuelle Bercot responds to Isild Le Besco Who is Deborah de Robertis, the artist who painted The Origin of the World?

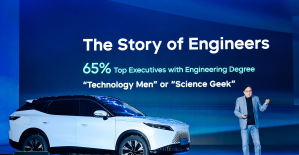

Who is Deborah de Robertis, the artist who painted The Origin of the World? Omoda 7, another Chinese car that could be manufactured in Spain

Omoda 7, another Chinese car that could be manufactured in Spain BYD chooses CA Auto Bank as financial partner in Spain

BYD chooses CA Auto Bank as financial partner in Spain Tesla and Baidu sign key agreement to boost development of autonomous driving

Tesla and Baidu sign key agreement to boost development of autonomous driving Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV The home mortgage firm rises 3.8% in February and the average interest moderates to 3.33%

The home mortgage firm rises 3.8% in February and the average interest moderates to 3.33% This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Europeans: David Lisnard expresses his “essential and vital” support for François-Xavier Bellamy

Europeans: David Lisnard expresses his “essential and vital” support for François-Xavier Bellamy Facing Jordan Bardella, the popularity match turns to Gabriel Attal’s advantage

Facing Jordan Bardella, the popularity match turns to Gabriel Attal’s advantage Europeans: a senior official on the National Rally list

Europeans: a senior official on the National Rally list Blockade of Sciences Po: the right denounces a “drift”, the government charges the rebels

Blockade of Sciences Po: the right denounces a “drift”, the government charges the rebels These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Mercato: Thiago Silva returns to Brazil and signs for Fluminense

Mercato: Thiago Silva returns to Brazil and signs for Fluminense Top 14: at what time and on which channel to follow the clash at the Toulouse-Stade Français summit?

Top 14: at what time and on which channel to follow the clash at the Toulouse-Stade Français summit? Tennis: Paula Badosa, former world No.2, passes the 1st round in Rome

Tennis: Paula Badosa, former world No.2, passes the 1st round in Rome Tour of Italy: Italian Jonathan Milan wins the 4th stage, Pogacar still leader

Tour of Italy: Italian Jonathan Milan wins the 4th stage, Pogacar still leader