The journey to a fascinating natural wonder in South America starts in a railway cemetery of all places. A little whimsical and surreal, but kind of fitting. Impressive steam locomotives once transported silver, minerals and above all salt from the Salar de Uyuni, the largest salt desert in the world, from southwest Bolivia to the Pacific coast of Chile.

In Europe, the 19th-century gems would be stars in any railway museum. But here, on the outskirts of Uyuni, a rather desolate backpacker town at an altitude of 3670 meters, the old steam locomotives are rusting away. Many are covered in graffiti. Tourists climb on them, looking for the best position for an original selfie.

"It's a really crazy place," says Carmen. She would like to take a few more photos of her boyfriend Christopher. Both studied together in Augsburg. Before they start their working life, they travel through Latin America for another three months. Guide Marco Arancibia calls the two and the rest of the group back to the 4x4. There's still a long day ahead of us, he says.

After just a few kilometers we reach Colchani, the gateway to the salt desert and the center of salt production. In a small family business, Marco explains how the salt is processed. More than a hundred years ago, people quarried huge blocks here and brought them to the local markets with llamas.

The salt is still extracted in a relatively traditional way today. With shovels it is piled up to dry in small mounds. The llamas have since been replaced by rust-eaten trucks. “The companies here mine up to 25,000 tons of salt every year. That sounds like a lot. But it's not, when you consider that the salar consists of around ten billion tons of salt," says Marco.

Colchani is the last place to buy snacks and water before heading into the infinite white.

Marco puts on his sunglasses and advises everyone to do the same. Now it goes into the salt flats. The guide steps on the gas. The salt crust crunches under the wheels of the Toyota Land Cruiser.

"Actually, it's not a desert at all, but a salt lake 140 kilometers long and 110 kilometers wide, on which a meter-thick crust of salt has formed," explains Marco while steering.

In total, this results in an area of around 10,600 square kilometers, making the Salar de Uyuni the largest salt flat in the world. Here's how it came into being: Plate drift separated the prehistoric Lake Minchin from the ocean millions of years ago and dried it up. Result: An almost endless salt pan.

In the rainy season between December and March, the salt desert is transformed back into a kind of lake when the knee-high layer of water on the salt crust makes the salar the largest mirror in the world. The breathtaking reflections allow heaven and earth to merge.

After half an hour we reach the salt hotel "Playa Blanca". The hotel is currently out of service. But the tour operators stop here for breaks. Tables, chairs or walls - everything is made of salt. Even the ball for the foosball table that our tour participants play while Marco prepares beef fillets with quinoa, vegetables, fried bananas and purple sweet potatoes.

Marco is a tour guide, driver, mechanic, cook and photographer all in one. For many years he has accompanied visitors to the salt flats for the tour operator World White Travel. The choice is large: there are more than 150 excursion companies in Uyuni.

It goes deeper into the desert or out onto the lake - depending on how you want to understand this quirky place. In the middle of nowhere, Marco stops again and gives Carmen and Christopher the choice of first fleeing a dinosaur or balancing on a gigantic wine bottle.

At first the two look skeptical. But then they find more and more fun in Marco's funny photo shoot. Due to the flat, almost endless surface, he skilfully plays with perspectives. He lies down on the salty ground and positions a rubber dinosaur directly in front of the cell phone camera, while the tourist couple appears tiny several meters behind. It looks like a giant dinosaur is attacking her in the photo.

Then they ride stuffed animal llamas and dance out of huts and backpacks. The wine bottle, which appears to be a meter high, is also amusing. But at some point it gets so crazy that you fear the sun was probably too strong during the photo shoot.

It goes on. Suddenly, black islands rise out of the white salt sea on the horizon. No mirages, but remnants of volcanic activity.

The only one of these islands that you can enter is called Incahuasi. In the indigenous Quechua language, the “house of the Inca” is called, says Marco. The Incas stopped here on their hikes through the salt desert. Even today, the indigenous tribes sacrifice llamas for the “Pacha Mama”, Mother Earth.

Incahuasi is almost 100 meters high and offers incredible views of the salar with its pentagonal salt honeycomb patterns. The island is covered with cacti up to twelve meters high. Considering that cacti grow an average of one centimeter a year, these specimens must be incredibly old.

How long will this natural wonder remain intact? Will the salt flats really become a national park as planned? Guide Marco is not sure. Bolivia is a poor country and there is a treasure slumbering under the salt - one of the largest lithium deposits in the world. The precious mineral is indispensable for the production of batteries for smartphones, tablets and cars.

Late in the evening we reach the salt hotel "Cruz Andina" on the edge of the salt pan. Even the bed and nightstand are made of blocks of salt.

The next morning we start early again, away from the salt lake. We drive over dusty slopes through barren stone and desert landscapes.

Outside the death zone, life begins again. Herds of vicunas - alpaca-like camels - graze in the unreal landscape. Smoke rises from the summit of the 5,870-meter Ollagüe volcano, which marks the border with Chile.

Shortly after the deep blue Cañapa lagoon, Marco drives into the Valle de Rocas, a bizarre rocky landscape in the middle of the Siloli desert with the famous "Arbol de Piedra", the stone tree. This is also the home of the viscachas, extremely friendly and frighteningly large rodents - if they get too close.

Not far away, the Laguna Colorada shimmers rust-red in the midday sun at an altitude of more than four kilometers. Llamas graze on the shore. In summer, up to 30,000 flamingos nest here on the small, white islets formed by the mineral borax.

The lagoon is located in Eduardo Avaroa National Park. As idyllic as it looks, the contrast is eerie, higher up, the Sol de Mañana geyser field. The landscape resembles the eerily gloomy Mordor from "Lord of the Rings".

It's bitterly cold. Smelly fumes of sulfur sweep over the steaming geyser field. It's hissing, bubbling and bubbling everywhere. burst mud bubbles.

But the earth, heated by the nearby volcanoes, can also be a real pleasure: the sandy track descends to 4400 meters, where you spend the night in a small, rustic hostel at the natural thermal springs of Polques.

At zero degrees, it takes a little effort after dinner to go to the hot springs and strip down to your swimming trunks. But as soon as you lie in the 38 degree warm pool, you are in seventh heaven. In the water you can watch the starry sky over the Bolivian desert.

In the morning, the hot, rising fog gives the lake landscape something mystical. You don't want to go any further. But halfway to Laguna Verde, the thermal baths are almost forgotten again, the Salvador Dalí desert is so grandiose and just as bizarre and surreal as the paintings by the famous Spanish painter, to whom it owes its name. The mountain ranges glow red, yellow or white - depending on how much iron, sulfur and volcanic ash the soil contains.

The nearby lagoons are just as colourful. In the Laguna Blanca, white borax dominates. In the Laguna Verde, the dormant Licancabur volcano is reflected in the deep green caused by the high lead and arsenic content of the water.

At the nearby border crossing to Chile at the Hito Cajon Pass, Christopher and Carmen say goodbye. They want to go further into the Atacama Desert.

Arrival: Airlines such as Iberia, LATAM or Air Europa fly from Germany to La Paz or Santa Cruz. From here you continue with the airline BoA or twelve hours by bus to Uyuni.

Entry: The Federal Foreign Office offers up-to-date information on its website.

Best time to visit: While the Salar de Uyuni can be visited all year round, the best times to visit are in spring (April and May) and autumn (September to November).

Operators: There are countless tour operators in Uyuni who offer day tours and excursions of up to three days. Three-day tours with prices up to US$150 are recommended. All head for the same attractions. The quality of food, accommodation and jeeps vary quite a bit. Recommended tour companies: worldwhitetravel.com; saltydesert-uyuni.com; quechuaconnection4wd.com; cordilleratraveller.com

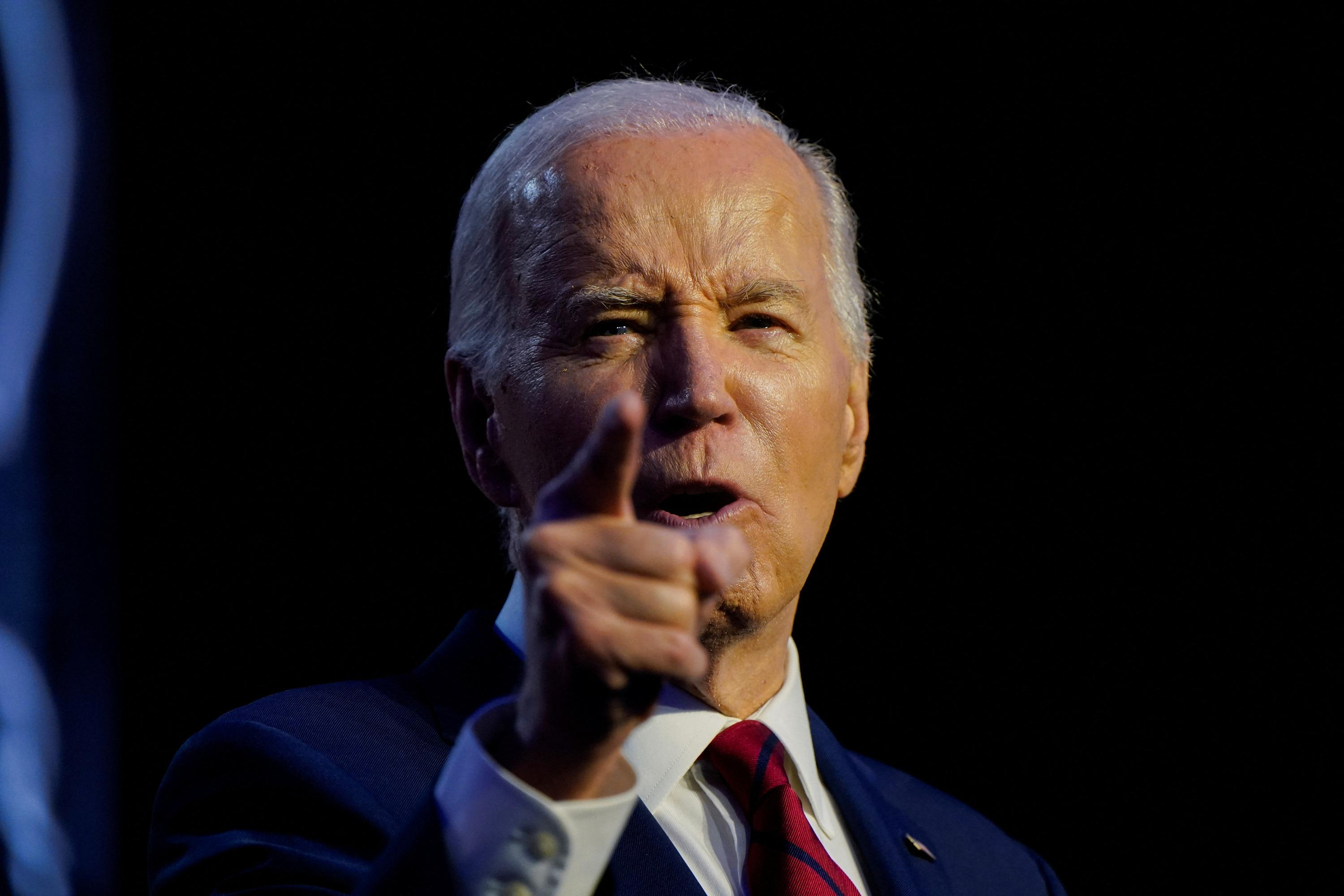

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza

Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza Israel prepares to attack Rafah

Israel prepares to attack Rafah Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Private clinics announce a strike with “total suspension” of their activities, including emergencies, from June 3 to 5

Private clinics announce a strike with “total suspension” of their activities, including emergencies, from June 3 to 5 The Lagardère group wants to accentuate “synergies” with Vivendi, its new owner

The Lagardère group wants to accentuate “synergies” with Vivendi, its new owner The iconic tennis video game “Top Spin” returns after 13 years of absence

The iconic tennis video game “Top Spin” returns after 13 years of absence Three Stellantis automobile factories shut down due to supplier strike

Three Stellantis automobile factories shut down due to supplier strike A pre-Roman necropolis discovered in Italy during archaeological excavations

A pre-Roman necropolis discovered in Italy during archaeological excavations Searches in Guadeloupe for an investigation into the memorial dedicated to the history of slavery

Searches in Guadeloupe for an investigation into the memorial dedicated to the history of slavery Aya Nakamura in Olympic form a few hours before the Flames ceremony

Aya Nakamura in Olympic form a few hours before the Flames ceremony Psychiatrist Raphaël Gaillard elected to the French Academy

Psychiatrist Raphaël Gaillard elected to the French Academy Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Archery: everything you need to know about the sport

Archery: everything you need to know about the sport Handball: “We collapsed”, regrets Nikola Karabatic after PSG-Barcelona

Handball: “We collapsed”, regrets Nikola Karabatic after PSG-Barcelona Tennis: smash, drop shot, slide... Nadal's best points for his return to Madrid (video)

Tennis: smash, drop shot, slide... Nadal's best points for his return to Madrid (video) Pro D2: Biarritz wins a significant success in Agen and takes another step towards maintaining

Pro D2: Biarritz wins a significant success in Agen and takes another step towards maintaining