At least one of this year's Nobel laureates in economics was already world-famous before the award: former US Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke (Brookings) received the world's most important economics prize together with Douglas Diamond (University of Chicago) and Philip Dybvig (Washington University).

"This year's award winners have significantly improved our understanding of the role of banks in the economy, especially in financial crises," said the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm, explaining its decision. "A key finding of their research is why it is so important to avoid bank failures."

The fact that the economy and banks strongly influence each other makes this sector particularly relevant. Because not only the bankruptcy of a state leads to bank failures. Conversely, the difficulties of banks can also drive an entire economy to ruin. A short economic crisis can even turn into a long-lasting economic depression.

In fact, it was mainly Bernanke who experienced this danger first-hand during his active time as currency guardian. His term of office coincided with the phase of the great financial crisis, when the entire financial system began to falter after the collapse of the US investment bank Lehman Brothers.

At that time, Bernanke, together with other central banks, braced himself against the impending collapse on the stock exchanges. Under his aegis, the Fed made large-scale purchases of Treasury and mortgage securities to bail out the world financial system. In doing so, he created the blueprint for the intervention policy of the central banks that is still valid today. Only recently, the Bank of England had massive access to domestic government bonds.

However, the Nobel Prize Committee made it clear that Bernanke does not receive the award for his work as a central banker, but for his research work on the Great Depression of the 1930s and its consequences.

“We are not passing judgment on whether or not he was a good central banker. Rather, we want to use it to highlight his research, in which he worked out how financial crises arise and what dimensions they can take," explained Tore Ellingsen, chairman of the Nobel Prize Committee for Economics.

In his 1983 research, Bernanke found that a functioning financial system is the lubricant of an economy. Banks would play a central role here by bringing together the interests of savers and borrowers. And not only with a view to the creditworthiness of the debtors, who constantly monitor the financial institutions for the savers.

Savers would prefer liquid assets in order to be able to access their money at any time. Borrowers, on the other hand, tend to want long-term contracts that offer a certain degree of planning security. In technical jargon, this is referred to as maturity transformation. Banks turn short-term savings into long-term loans. And here special trust of the actors is necessary.

Bernanke (68), who now works at the Brookings Institution in Washington, has shown in his research how dangerous a run on banks can be, for example when savers withdraw their deposits in panic or companies can no longer get loans or only at horrendous costs , because no one wants to spend their money on long-term anymore.

His fellow laureates Diamond, 68, from the University of Chicago, and Dybvig, 67, from Washington University in St. Louis, have shown in their theoretical work, which has now also been awarded the Nobel Prize, how state guarantees for deposits such bank runs and thus prevent a spiral of financial crises.

The research of the laureates is not only limited to banks, but also highly relevant elsewhere in the financial sector. In Germany, for example, there was a storm on open-ended real estate funds during the financial crisis. Since the providers could not create liquidity so quickly, many funds had to close temporarily and investors could not get their money.

In order to prevent such runs, which would in fact have the effect of foreclosures, there are now statutory holding and return periods. The different maturities are particularly evident in the case of open-ended real estate funds: Real estate cannot simply be sold at short notice like shares or bonds, but the shares in the funds were tradable on a daily basis until the legal change.

All forms of investment that can be liquidated in the short term, which are offset by longer-term assets, are susceptible to turbulence and crises, said Douglas Diamond, one of the laureates who was connected live from America shortly after the Nobel Prize was announced. While the banks are now quite well prepared for such crises, so-called shadow banks such as investment managers or insurance companies still pose risks.

The Bank of England, for example, was only forced to intervene in the bond market at the end of September, as British pension funds were unable to provide sufficient short-term collateral, which had become necessary after the rise in interest rates on British gilts.

However, providers of index funds, so-called ETFs, are also conceivable, which in the event of a wave of sales could only get rid of the underlying assets at bargain prices and thus no longer be able to keep their promise to map a specific index.

Experts see risks in ETFs that invest in high-yield bonds. Such debt securities are not so easy to sell. The more forms of investment that can be traded via liquid vehicles, the more susceptible the financial system is to stress. "Limitless liquidity is incompatible with universal stability," Diamond said.

The scientist from the University of Chicago was the only one of the three laureates whom the Swedish Royal Academy was able to reach by telephone shortly after the decision was made: neither Bernanke nor Dybvig knew anything about their award at the time of the press conference.

On the one hand, the fact that this year's Nobel Prize honors economists who have made outstanding contributions to research into financial crises is appropriate at the time: During the pandemic, as in 2008, there was a risk that the global economy would slide into a depression, said Ellersen.

The research area is therefore still highly relevant, especially since the currently rising interest rates are once again documenting how vulnerable the financial system is. On the other hand, the Nobel Prize Committee attaches great importance to the prize having a timeless character.

"When awarding the prize, we don't take into account whether or not now is the right time for the topic," emphasized Ellersen. It is all about the scientific contribution and the relevance within the economy.

However, with Bernanke, a currency guardian is now being honored for the first time, who is largely responsible for the imbalances that have built up in the global financial system since 2008. Because the years of flood of liquidity from the central banks has its price, as shown by the speculative bubbles in shares and real estate and the currently rapidly rising inflation.

The three laureates also feel the consequences of this. The Nobel Prizes are endowed with 10 million Swedish crowns, there is no inflation adjustment. The crown has lost a good fifth of its value in the past twelve months, so that the ten million crowns are currently only worth $886,000.

It is striking that the Swedish Royal Academy has once again closed itself to the zeitgeist in the selection of its Nobel Prize winners in economics: Instead of choosing at least one woman among this year's laureates, as predicted, only male economists were once again honored.

Since the first Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded in 1969, only two women have been awarded the prize, so the male quota for the Nobel Prize in Economics is 98 percent: The two previous winners are Elinor Ostrom in 2009 and Esther Duflo 2019, who was 46 at the time is also the youngest ever recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economics.

The committee has also remained true to itself when it comes to age. According to an analysis by Barkow Consulting, the average Nobel laureate is 68 years old, 83 percent live in the United States and most, namely 15 percent, teach in Chicago. That is true once again for this year's cohort.

In contrast to the other Nobel awards, the Nobel prize for economics was not established by Alfred Nobel in his will from 1895. Instead, the Swedish central bank awarded this category for the first time in 1969 in memory of Nobel. Last year, the Nobel Prize in Economics went to the economists David Card, Joshua Angrist and Guido Imbens for their suggestions for empirical research, for example in the labor market or in the education system.

"Everything on shares" is the daily stock exchange shot from the WELT business editorial team. Every morning from 7 a.m. with our financial journalists. For stock market experts and beginners. Subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Amazon Music and Deezer. Or directly via RSS feed.

Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza

Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza Israel prepares to attack Rafah

Israel prepares to attack Rafah Indifference in European capitals, after Emmanuel Macron's speech at the Sorbonne

Indifference in European capitals, after Emmanuel Macron's speech at the Sorbonne Spain: what is Manos Limpias, the pseudo-union which denounced the wife of Pedro Sánchez?

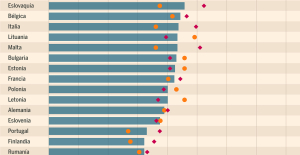

Spain: what is Manos Limpias, the pseudo-union which denounced the wife of Pedro Sánchez? Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Private clinics announce a strike with “total suspension” of their activities, including emergencies, from June 3 to 5

Private clinics announce a strike with “total suspension” of their activities, including emergencies, from June 3 to 5 The Lagardère group wants to accentuate “synergies” with Vivendi, its new owner

The Lagardère group wants to accentuate “synergies” with Vivendi, its new owner The iconic tennis video game “Top Spin” returns after 13 years of absence

The iconic tennis video game “Top Spin” returns after 13 years of absence Three Stellantis automobile factories shut down due to supplier strike

Three Stellantis automobile factories shut down due to supplier strike A pre-Roman necropolis discovered in Italy during archaeological excavations

A pre-Roman necropolis discovered in Italy during archaeological excavations Searches in Guadeloupe for an investigation into the memorial dedicated to the history of slavery

Searches in Guadeloupe for an investigation into the memorial dedicated to the history of slavery Aya Nakamura in Olympic form a few hours before the Flames ceremony

Aya Nakamura in Olympic form a few hours before the Flames ceremony Psychiatrist Raphaël Gaillard elected to the French Academy

Psychiatrist Raphaël Gaillard elected to the French Academy Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Judo: Blandine Pont European vice-champion

Judo: Blandine Pont European vice-champion Swimming: World Anti-Doping Agency appoints independent prosecutor in Chinese doping case

Swimming: World Anti-Doping Agency appoints independent prosecutor in Chinese doping case Water polo: everything you need to know about this sport

Water polo: everything you need to know about this sport Judo: Cédric Revol on the 3rd step of the European podium

Judo: Cédric Revol on the 3rd step of the European podium