The ancient historians were surprisingly unanimous about the Empress Valeria Messalina (before 18–48). Tacitus attested to her drive for "unknown desires", Suetonius permanent adultery and Cassius Dio the organization of veritable sex orgies in the palace. According to these testimonies, Messalina was one of the greatest nymphomaniacs of antiquity.

One of the reasons for this characterization was Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, simply called Claudius, and he had been Emperor of Rome since the year 41. He made it easy for his contemporaries to deride him as a cuckold who, in his "passionate love for Messalina" (Suetonius), simply ignored her antics. And they did it with great enthusiasm, for Claudius was not very popular, since by the time he died in 54 he had evidently sentenced to death numerous senators and knights whom he suspected of conspiracy.

It had been pure coincidence that Claudius had come to the throne. As the son of Augustus' adoptive son Drusus, who died early, he belonged to the Julio-Claudian dynasty, but suffered from numerous disabilities from birth. He had a limp and had trouble speaking, so Augustus kept him from public view. When Claudius' nephew Caligula was killed by the Praetorians in 41, they discovered the trembling 50-year-old behind a curtain and immediately proclaimed him the new Emperor. Thus Claudius' third wife Messalina unexpectedly became the empress.

The ancient historian Werner Eck countered the assumption that Messalina was only 15 years old at the time in his detailed study of “The Women Next to Caligula, Claudius and Nero”. She was probably at least 20 years old, if not over 25, and not only was she an attractive beauty from the best of society, she was also distantly related to Augustus. It could well be the case, Eck concludes, that the marriage to the unloved prince was intended to seal an alliance between two powerful families.

Anyway. Research has long since worked out that the negative picture that the ancient sources paint of Claudius only corresponds to a limited extent to reality. The conquest of Britain began under his reign, he took care of the administration of justice and the improvement of the infrastructure, and is said to have written a considerable (albeit lost) literary work. But his tendency to rely on the advisers who had served him before he came to the throne alienated him from the Senate aristocracy. Because they were freedmen or other outsiders from better society, with whom a prince with no prospect of the throne had to make do.

Politically inexperienced as he was, the emperor allowed himself to be controlled by those around him, and Messalina was a crucial part of that. At the end of the 1st or beginning of the 2nd century, the poet Juvenal summed up what was said about her in a bitterly angry satire: At night she was said to have moved “to the muggy brothel” with a blond wig, where she was naked and with gilded breasts offered the customers "and lying on her back, she swallowed the thrusts of many".

Admiral Pliny the Elder, a contemporary witness, also described the mating forms of the animals in his “Natural History”. Messalina was presented as an extreme example, having achieved 25 concubitus in 24 hours in competition with the most famous whore in Rome. In the palace, on the other hand, she asked aristocrats to “give themselves to others in front of their husbands,” writes Cassius Dio.

None of this can be verified, and similar reports from other emperors and their courts show that sex fantasies were a common means of defamation in Rome. It is also quite possible that Messalina's successor in Claudius' marriage bed, Agrippina the Younger, Nero's mother, deliberately spread such stories in order to discredit Messalina's memory. But the readers were obviously attuned to such images, argues Werner Eck: "So a corresponding characterization must have been associated with Messalina at the time."

A well-known affair in the fall of '48, perhaps sometime in November, provided a lot of material. Messalina celebrated a festival with her current lover, the beautiful Silius, which was generally understood as a wedding ritual. This alarmed the high-ranking freedmen in the imperial household, who had assisted her in numerous intrigues by slandering rivals or competitors to Claudius, who then signed the death penalty.

That both Claudius and Messalina lived in an open relationship was still acceptable, although this contradicted Augustus' strict marriage laws. The fact that the wife dissolved the marriage through bigamy allowed only one consequence: In order to forestall the foreseeable deadly reaction of her husband, the newlyweds had to put themselves at the head of a conspiracy against the Emperor according to the political rules of the time. If successful, the freedmen would lose their boss and probably their heads as well. So they immediately switched sides.

Narcissus, one of the emperor's closest advisors, rushed to Ostia where his master was on business. There he is said to have presented him with a list of all his wife's lovers and informed him about the consequences of the wedding for him. Claudius then hurried back to Rome. When Messalina heard this, she once again relied on her charisma and the fact that she had given birth to the heir to the throne in Britannicus. But before he got the chance to soften, Narcissus had given the praetorians the order to kill. Beautiful Silius was smart enough to ask for an easy death.

Was Messalina really stupid enough not to overlook the consequences of her escapades? The construction of the intrigues that she is said to have spun speak against a lack of intelligence. Perhaps the experience of successfully getting out of affairs with her husband had blinded her judgment.

Maybe just carpe diem (enjoy the day) had become their maxim. If one includes all possible and probable falsifications, Eck writes, "there is enough to see in Valeria Messalina a woman driven by her passions, who also considered the prospects of her children, whom she had borne to Claudius, and thus her own, but who was not able to subordinate or at least classify their emotionality to them in the long term".

You can also find "World History" on Facebook. We are happy about a like.

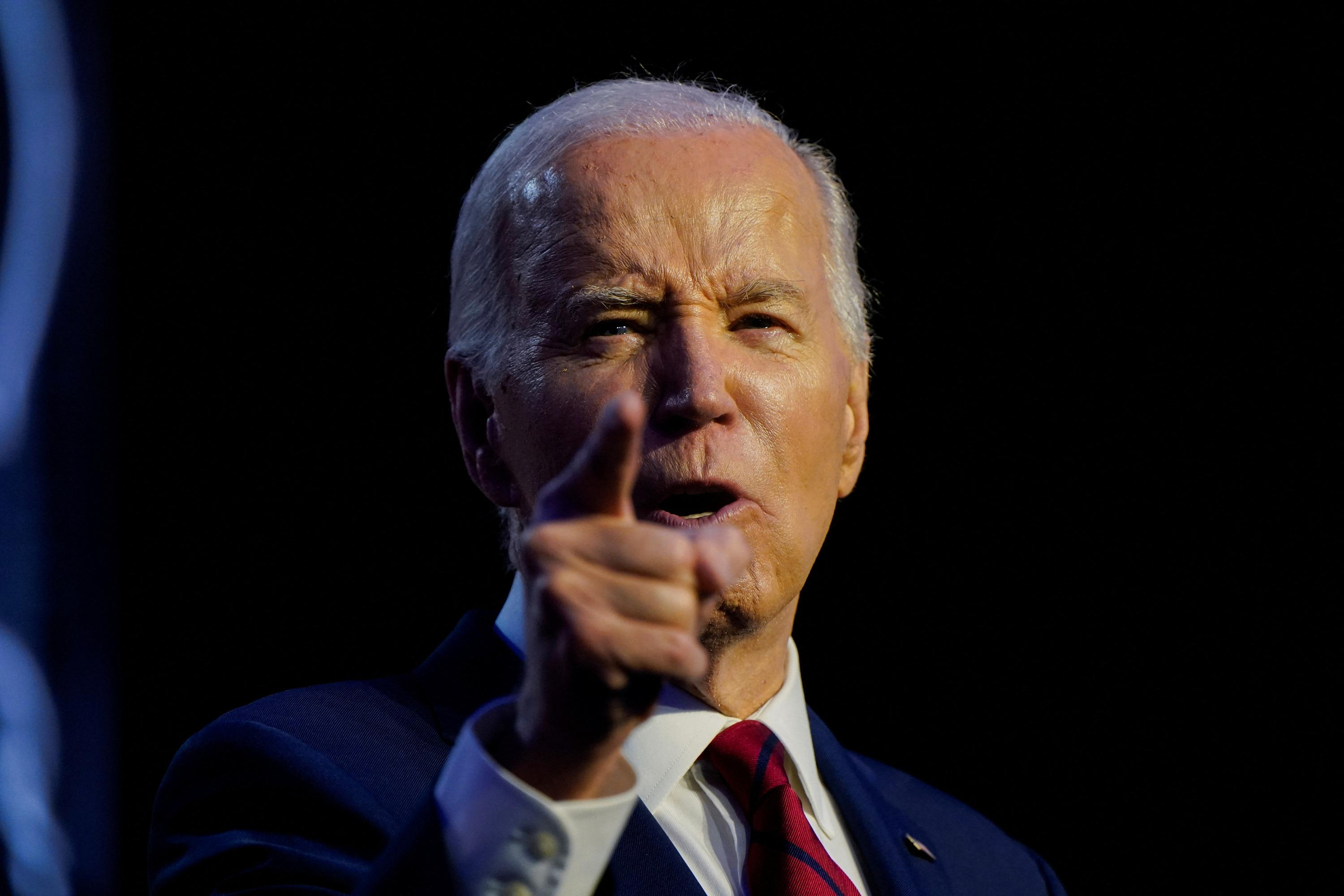

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza

Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza Israel prepares to attack Rafah

Israel prepares to attack Rafah Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Private clinics announce a strike with “total suspension” of their activities, including emergencies, from June 3 to 5

Private clinics announce a strike with “total suspension” of their activities, including emergencies, from June 3 to 5 The Lagardère group wants to accentuate “synergies” with Vivendi, its new owner

The Lagardère group wants to accentuate “synergies” with Vivendi, its new owner The iconic tennis video game “Top Spin” returns after 13 years of absence

The iconic tennis video game “Top Spin” returns after 13 years of absence Three Stellantis automobile factories shut down due to supplier strike

Three Stellantis automobile factories shut down due to supplier strike A pre-Roman necropolis discovered in Italy during archaeological excavations

A pre-Roman necropolis discovered in Italy during archaeological excavations Searches in Guadeloupe for an investigation into the memorial dedicated to the history of slavery

Searches in Guadeloupe for an investigation into the memorial dedicated to the history of slavery Aya Nakamura in Olympic form a few hours before the Flames ceremony

Aya Nakamura in Olympic form a few hours before the Flames ceremony Psychiatrist Raphaël Gaillard elected to the French Academy

Psychiatrist Raphaël Gaillard elected to the French Academy Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Archery: everything you need to know about the sport

Archery: everything you need to know about the sport Handball: “We collapsed”, regrets Nikola Karabatic after PSG-Barcelona

Handball: “We collapsed”, regrets Nikola Karabatic after PSG-Barcelona Tennis: smash, drop shot, slide... Nadal's best points for his return to Madrid (video)

Tennis: smash, drop shot, slide... Nadal's best points for his return to Madrid (video) Pro D2: Biarritz wins a significant success in Agen and takes another step towards maintaining

Pro D2: Biarritz wins a significant success in Agen and takes another step towards maintaining