This text begins with a confession: In the presence of the author, the reviewer was often very drunk. Behzad Karim Khani is a medium-sized figure in Berlin's nightlife, owner of the Kreuzberg Lugosi Bar, not far from Görlitzer Park, where you can buy pretty much every illegal drug in the world.

You have to tell us briefly what it looks like in this bar: unplastered walls, mercifully dim light, a record player and fresh lilies, the scent of which some smell of decay mixes with cigarette smoke (in front of the non-smoker protection law, anyway).

The legal drug alcohol comes in the form of strong, sometimes very strong, drinks. I spent what feels like half of my studies in this bar and was always amazed when the owner personally grabbed a tumbler because he didn't want to fit in at all with this place. Khani seemed too delicate, fragile like the long-stemmed wine glasses behind him, and always surrounded by a faint sadness.

I tell you this because I found all of these aspects – the seductive murmur of darkness, the illusion of immortality of a Kreuzberg night and a man whose soul is at least half elsewhere – in Khani's debut novel.

"Hund Wolf Jackal" is the literary answer to the clan series "4 Blocks", even if the author coquettishly wipes this claim aside in a "Zeit" interview. This book had to be written by someone, after all, half of Germany is gossip-splitting about the Neukölln nepotism, the Abou Chakers, Al Zeins and whatever they are called, with their sharp boxers and even sharper bitches.

Berlin isn't just the city where school toilets stink and citizens' office appointments are made on the Darknet, but also the city where the enemy is marked with initials carved into the flesh. At least that's what Saam observes, growing up in revolutionary Iran as the son of rebellious parents. His mother was killed in a torture prison and his father had his leg shot off.

Together with the younger brother Nima, the three flee to Berlin, where the taxi-driving father keeps his pride by not accepting gifts and scouring the remains of dog poop off the street. It takes years for what the cliché envisions for every immigrant youth to happen: “They were ghetto plankton. Cells that the wind could drive before it. ... A flicker. An irritation. A conflict.”

After a bit of dealing and stripping, he commits armed robberies with a buddy, one of which goes wrong in that the pharmacist, who is also armed, puts a nine-millimeter projectile into Saam's upper arm, which indirectly leads to his arrest. The protagonist, who has barely outgrown his teenage years, serves his sentence for six years, sometimes in solitary confinement.

His brief feeling of having found a place of arrival in the extreme judicial structure is reminiscent of Christian Kracht's "1979", perhaps also because its action is also based in revolutionary Iran. But soon it turns into pure paranoia, the constant fear that one of his enemies might take revenge on him, which eventually becomes reality.

The newcomer to the literature business (Khani has previously written essays and journalistic texts, also for WELT) has already presented part of this prison passage at the Bachmann competition. He did not put into practice the plan to recite his text with a razor blade in his mouth. The Klagenfurt excerpt is a strong, but not the strongest passage in the book because it is completely limited to the inwardness of its main character - Khani's specialty is observing the smallest particles of the world and a poetry of the ugly.

Sleeping swans look like “disdained wedding dresses”, the time in the corner pub passes “tenderly with fine dust” and the immigration office smells of “old people’s kitchen cupboards and opened minced meat packages”. Whereby the bitter tale occasionally allows for a grotesque sense of humour: pink Snoopy sweaters fall off trucks, which become a trend as a result of a marketing coup ("You can also dye them. Women can wear them too. Children. S is also there"). , men stare at Mc Donald's economy menus "like at the last sunset of a holiday that is too short". A misspelling engraved on the gun is just prevented by a Mister Minit employee.

The view from the outside of a country that oscillates somewhere between peepholes, official German and the dictatorial philistinism of an allotment colony is great fun. “In the stairwell, rubber trees were planted in pots filled with granulate, from which moisture meters protruded like clinical thermometers. The shoemats' dense, bread-brown brush hair was so flawless you'd think their owners came home from a cleaner world.” In stark contrast is Saam's world of clicking butterfly knives and knocked-out teeth.

Of course, the "Kanakendeutsch" also has its place here, the missing articles and wrong prepositions, the "yallah, brother" and "was Clans, Alter? What gangster?” A successful contrast to this is the straightforward language of the authorial narrator, with short sentences that get straight to the point, like a would-be gangster robbing a gas station.

The subdivision of the plot into short chapters with allusive headings has a supporting effect: luck, meat, dust, zero. The hard realism, in turn, is broken up by surreal elements, which can be traced back to Saam's mental instability. A fully tattooed man with scars appears to him repeatedly, who sometimes pays his bills, sometimes ensures that he only loses half, not all, of his mind in solitary confinement.

Khani's talent for storytelling probably runs in the family. His father is also an author, Foucault was on the bookshelf, so the son, who wrote poetry as a child, is a “child of well-read parents”, just like his antihero. At this point at the latest, the tiresome question of biographical parallels arises. Khani was born in Tehran in 1977 and fled from there with his family to the Ruhr area in 1986. He has a criminal record, but also a high school diploma. In 2001, the self-described "Edel-Kanake" came to Berlin after dropping out of his studies in art history and media studies. In the book, Saam's younger brother Nima downs some vodka shots there.

Which parts of the rest of the plot are fictitious remains the author's secret. Miniature pinschers killing Doberman puppies, teen girls rinsing the blowjob disgust out of their mouths with Fisherman's Friends (women, just for the sake of completeness, come up in this testosterone territory only as saints and whores, the former in the form of mother, sister, wife, their honor is to be protected, the latter in the form of prostitutes) – dit is Berlin? At least the description of Neukölln's Sonnenallee as "the street that was most Tehran. Because nothing worked and yet everything survived” withstands the reality check.

The fact that reading is not only accompanied by a pleasant parallel world horror, but also linguistic beauty and even tender moments speaks for Khani's literary talent. Apparently he used his years behind the bar to observe the light and shadows on the faces of his guests very closely. In an interview, the Berliner-by-choice made it clear: “I have now worked at night for 25 years. I've heard everything that people can say to each other.” That he wrote it down is very fortunate.

Behzad Karim Khani: "Dog Wolf Jackal". Hanser Berlin, 288 pages, €24.

War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives

War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza

Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte

First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025

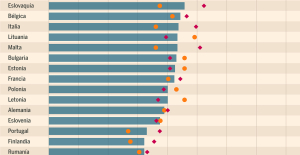

Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025 Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Inflation rebounds in March in the United States, a few days before the Fed meeting

Inflation rebounds in March in the United States, a few days before the Fed meeting Video games: Blizzard cancels Blizzcon 2024, its annual high mass

Video games: Blizzard cancels Blizzcon 2024, its annual high mass Falling wings of the Moulin Rouge: who will pay for the repairs?

Falling wings of the Moulin Rouge: who will pay for the repairs? “You don’t sell a company like that”: Roland Lescure “annoyed” by the prospect of a sale of Biogaran

“You don’t sell a company like that”: Roland Lescure “annoyed” by the prospect of a sale of Biogaran Exhibition: in Deauville, Zao Wou-Ki, beauty in all things

Exhibition: in Deauville, Zao Wou-Ki, beauty in all things Dak’art, the most important biennial of African art, postponed due to lack of funding

Dak’art, the most important biennial of African art, postponed due to lack of funding In Deadpool and Wolverine, Ryan and Hugh Jackman explore the depths of the Marvel multiverse

In Deadpool and Wolverine, Ryan and Hugh Jackman explore the depths of the Marvel multiverse Tom Cruise returns to Paris for the filming of Mission Impossible 8

Tom Cruise returns to Paris for the filming of Mission Impossible 8 Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Basketball: Strasbourg appeals the victory recovered by Monaco

Basketball: Strasbourg appeals the victory recovered by Monaco Top 14: UBB with Tatafu and Moefana against Bayonne

Top 14: UBB with Tatafu and Moefana against Bayonne MotoGP: Bagnaia dominates qualifying practice in Spain and sets track record

MotoGP: Bagnaia dominates qualifying practice in Spain and sets track record Olympic Games: in Athens, Greece transmits the Olympic flame to France

Olympic Games: in Athens, Greece transmits the Olympic flame to France