Sometimes bureaucrats themselves betray their misanthropic thinking. For example, a Stasi officer who wrote about a young person in Weimar that he was working “for a more humane society in the GDR”. So it has to be "edited". "Processing" meant in MfS jargon: monitor, intimidate, "decompose".

Matthias Domaschk also strove for a more humane society in the GDR. The young man from Jena, born in 1957, was looking for his own way in "actually existing socialism". He caused offense because he wanted to live independently with his friends. At least as self-determined as it was possible in the SED dictatorship. Therefore, the Stasi considered him a "relevant person"

On April 10, 1981, Matthias "Matz" Domaschk and his friend Peter Rösch, known as "Blase", boarded the express train to East Berlin in Jena. Her goal: a birthday party. Departure 6:19 p.m., arrival 10:14 p.m. But they did not reach their goal. Around 8.40 p.m. on this Friday evening, the train stopped in Jüterborg south of Berlin. A little later, several uniformed men entered the compartment in which Domaschk and Rösch were sitting, asked them for their IDs (the tickets were of no interest) and asked them to get out.

The reason? "By order of a higher authority." The two friends did as ordered, they didn't want any trouble. This is how the last 41 hours of Matthias Domaschk's life began. Now, more than four decades later, the journalist Peter Wensierski has reconstructed this time – in his book “Jena-Paradies” (Ch. Links Verlag. 367 p., 25 euros)

The story is mostly told from two parallel perspectives – that of Matthias, his friends and family on the one hand, and that of the Stasi and other “armed organs” of the SED state on the other. Wensierski's trick is sometimes a bit confusing, because the "Contrasts" and later "Spiegel" editor sometimes has to jump back and forth in the time sequence. But once the reader gets used to it, the structure of the book develops a pull that draws you in.

Wensierski spoke to all of Domaschk's acquaintances who could still be reached, even interviewed several of the Stasi people involved at the time, of course pored over files and visited the scenes of the events (often disappeared or at least completely changed).

In some places, however, he also had the proverbial luck of a reporter – verifiable with photos and therefore without any suspicion of Relotius, which one should always check with “Spiegel”. For example at Jüterborg station. Little has changed at the station building since 1981 – apart from the fact that, after being vacant for a long time, the inside is even more run-down than it was in GDR times. Wensierski's descriptions often give his book an oppressive authenticity.

So why was the Stasi interested in Matthias Domaschk of all people? Like his circle of friends, he was considered nonconformist and oppositional, a potential troublemaker. This was suspicious in the SED dictatorship and regularly triggered "processing" by the MfS. But not necessarily an arrest or worse.

But from the point of view of the Stasi, Domaschk and Rösch's trip to East Berlin on April 10, 1981 fell on a special day. There, in the “capital of the GDR”, the party congress of the SED was to begin the following morning, a celebration of the state party only staged every five years. The Stasi apparently feared that the two friends would protest publicly, as other members of the Young Community in Jena had done again and again.

In any case, Major Herbert Würbach from the MfS district office in Jena received clear instructions from his superior, Colonel Werner Weigelt from the MfS district administration in Gera this Friday at around 7:15 p.m.: “These people are not allowed to enter the capital!”

That set the tone: danger was imminent, Domaschk and Rösch had to be stopped! The members of the "organs" behaved accordingly in the hours that followed. They could have acted less harshly, less threateningly - but they didn't.

Wensierski reconstructs in detail what happened to the two friends from Jena in the hours that followed: They were intimidated, separated from one another and interrogated harshly for hours. Peter Rösch remembered the scarcely disguised threats until, at midday on Sunday, April 12, 1981, he was suddenly informed that he was being released and taken back to Jena.

In the early afternoon, at almost exactly 2:15 p.m., Rösch entered the prison courtyard where a Stasi prisoner transporter was waiting for him, when he suddenly heard a doctor being called from inside the building. Rösch worried that his friend Matz might have suffered a circulatory collapse from the nightly interrogations without sleep.

The reality was much worse. Just like Rösch, Domaschk had been put under massive pressure. He faces jail. it was said. Finally "Matz" signed a "declaration of commitment". He wanted to support "the MfS in the fight against the enemies of the GDR actively and without any reservations". The words were dictated to him by a Stasi officer, Captain Horst Hanno Koehler. The handwritten declaration on lined paper ended with the words "For the conspiratorial cooperation with the MfS I choose the alias 'Peter Paul'." Then the place, Gera, the date, April 12, 1981, and finally the signature: Matthias Domaschk.

With this forced "obligation" the Stasi officer Koehler had achieved his goal. At 1:45 p.m., another MfS man brought the completely exhausted "Matz" to a visitor's room in the Stasi prison in Gera, handing him his parka, which he had left in the interrogation room.

Wensierski spoke to the Stasi lieutenant who was the last person to see Matthias Domaschk alive. Barely half an hour later, the same secret police officer returned to the visitor's room - and found "Matz" hanging lifeless from a heating pipe. It was hanging from a sleeve of his own shirt.

According to the latest research, everything indicates that Domaschk committed suicide out of desperation after being forced to spy for the MfS. There is therefore no solid evidence to support the suspicion that Stasi people hung him up to cover up a fatal collapse during interrogation.

This does not change anything about the responsibility of the MfS for his death. Wensierski rightly quotes a friend of "Matz" from the Jena peace community: "For me it's crucial where he died. I don't care if he fell down the stairs, if he choked and suffocated, if he was beaten to death, or if he committed suicide. None of that matters. The only thing that always mattered was the place and that he didn't go to that place voluntarily.”

If you have the feeling that you need help, please contact the telephone counseling immediately. You can call the toll-free number 0800-1110111 or 0800-1110222 to get help from advisors who can show you ways out of difficult situations. The German Society for Suicide Prevention offers further help.

You can also find "World History" on Facebook. We are happy about a like.

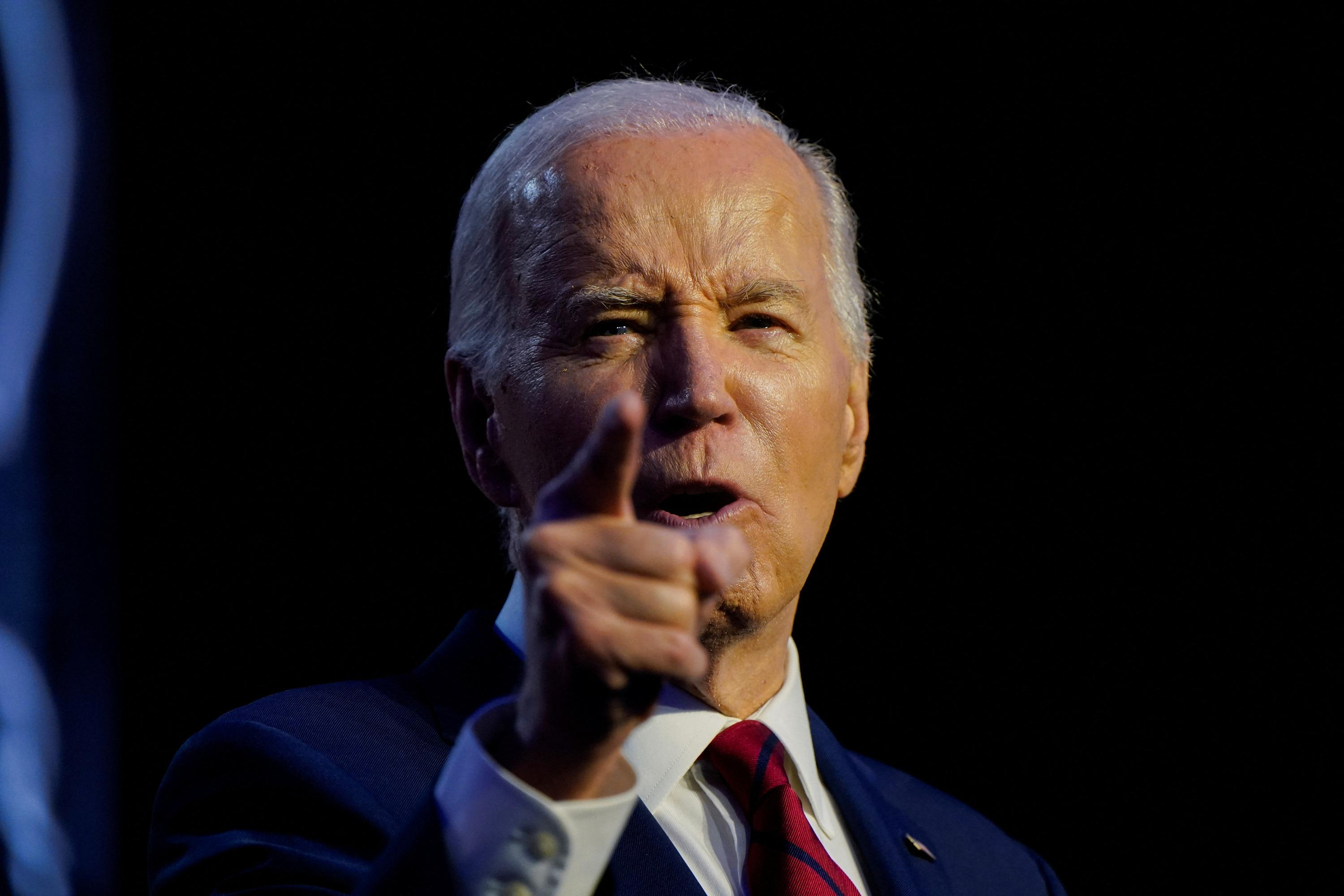

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza

Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza Israel prepares to attack Rafah

Israel prepares to attack Rafah Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Private clinics announce a strike with “total suspension” of their activities, including emergencies, from June 3 to 5

Private clinics announce a strike with “total suspension” of their activities, including emergencies, from June 3 to 5 The Lagardère group wants to accentuate “synergies” with Vivendi, its new owner

The Lagardère group wants to accentuate “synergies” with Vivendi, its new owner The iconic tennis video game “Top Spin” returns after 13 years of absence

The iconic tennis video game “Top Spin” returns after 13 years of absence Three Stellantis automobile factories shut down due to supplier strike

Three Stellantis automobile factories shut down due to supplier strike A pre-Roman necropolis discovered in Italy during archaeological excavations

A pre-Roman necropolis discovered in Italy during archaeological excavations Searches in Guadeloupe for an investigation into the memorial dedicated to the history of slavery

Searches in Guadeloupe for an investigation into the memorial dedicated to the history of slavery Aya Nakamura in Olympic form a few hours before the Flames ceremony

Aya Nakamura in Olympic form a few hours before the Flames ceremony Psychiatrist Raphaël Gaillard elected to the French Academy

Psychiatrist Raphaël Gaillard elected to the French Academy Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Archery: everything you need to know about the sport

Archery: everything you need to know about the sport Handball: “We collapsed”, regrets Nikola Karabatic after PSG-Barcelona

Handball: “We collapsed”, regrets Nikola Karabatic after PSG-Barcelona Tennis: smash, drop shot, slide... Nadal's best points for his return to Madrid (video)

Tennis: smash, drop shot, slide... Nadal's best points for his return to Madrid (video) Pro D2: Biarritz wins a significant success in Agen and takes another step towards maintaining

Pro D2: Biarritz wins a significant success in Agen and takes another step towards maintaining