Just eat a roll from the bakery or a doner kebab on the go - this is not possible for people with a gluten intolerance. You have to find substitutes for many foods. That requires discipline and patience. According to the German Celiac Society (DZG), about one percent of the population is affected by so-called celiac disease, which would be more than 800,000 people in Germany alone.

Celiac disease is a small intestinal intolerance to gluten found in some grains. The contact of the intestinal mucosa with gluten, also known as gluten, causes the intestinal villi – countless protuberances on the surface of the small intestine – to flatten out over time and be able to absorb smaller amounts of nutrients. This can cause digestive problems, but also many other health problems. A study is now showing progress that could lead to a tolerable handling of it.

Gluten is found in cereals such as wheat, spelt, rye and barley, which is why normal baked goods are taboo for those affected. According to the DZG, the gluten protein can also be found in other foods in which one would not necessarily suspect it. It can be contained in ice cream, spice mixtures, fruit juices or spreads.

"Strictly speaking, it is neither an allergy nor an intolerance," says Stephanie Baas, medical consultant at the DZG, but an autoimmune disease. So far, the only chance of getting the disease under control is to avoid foods containing gluten for life.

Because if the mucous membrane of the small intestine comes into contact with gluten, celiac disease is activated again and again. This makes it harder for the body to absorb nutrients. This can affect the stability of the bones and lead to osteoporosis. The fulfillment of a desire to have children can sometimes fail due to celiac disease.

According to Baas, a gluten-free diet is generally free of side effects, but many substitute products contain more fat and sugar in order to produce a normal taste. "We know that some celiac patients also have a problem with it, such as gaining excessive weight," says Baas.

According to Christian Sina, Director of the Institute for Nutritional Medicine in Lübeck, gluten-free diets (GFD) - i.e. the strict avoidance of gluten - do not work equally well for all those affected. In some patients, such a diet hardly works. Therefore, it is necessary to find new therapeutic approaches.

According to Baas, research is trying to find drugs that make life easier for those affected. A remedy that enables patients to eat “normally” is not in sight for the time being.

There might be some relief in a few years. Hopes are currently pinned on a so-called transglutaminase inhibitor. A working group led by Detlef Schuppan, head of the clinic for celiac disease, small intestine diseases and autoimmunity at the University Medical Center Mainz, developed the transglutaminase 2 inhibitor ZED1227 together with two companies and tested it for safety and effectiveness in a Europe-wide study.

A total of 160 patients in Germany, Switzerland and five other European countries took part in the study. They generally ate a gluten-free diet—but during the six-week study, they all ate a biscuit containing three grams of gluten in the morning. About 120 participants took the active substance ZED1227 in different dosages, the remaining subjects received a placebo and served as a control group.

In fact, the drug largely prevented inflammation and damage to the intestinal villi, the team reported in the New England Journal of Medicine (“NEJM”) in the summer of 2021. Side effects such as nausea, diarrhea, vomiting and headaches occurred in the treated participants as often as in the control group.

Michael Schumann from the Berlin Charité, coordinator of the German celiac disease guideline, explains the possible mechanism of action of the preparation as follows: The enzyme transglutaminase expressed in the intestinal mucosa changes the proteins present in gluten in such a way that they can trigger an immune reaction in celiac disease patients. The hope behind the enzyme inhibitor is: "If I switch off the activity of transglutaminase with an inhibitor, then I can get the activity of the patient's celiac disease under control."

Since there are many different enzymes and also several transglutaminases in the body, it is important to only inhibit the transglutaminase that triggers the immune reaction in the intestine. That was successful in the study, says Schumann, who was involved in the work himself. This is the first time that success has been shown in humans on the structure of the small intestinal mucosa. The preparation has reduced the gluten-related inflammation and the loss of villi in the small intestine.

The drug is currently being tested again in a larger study in more than 20 countries, including at a good 20 German centers. Schuppan expects results in 1.5 to 2 years. In the new study, the treatment lasts longer – 17 weeks instead of the previous 6 weeks. 400 to 450 celiac disease patients who, despite a gluten-free diet, have residual symptoms such as abdominal pain or diarrhea should take part.

According to Schumann, if the drug were approved, it would be aimed at this target group in order to prevent or alleviate such symptoms. "From the point of view of those affected, that would be a great thing," says Schumann.

If these and other studies are successful, the drug could possibly be approved in about four to five years, says Schuppan. He emphasizes that the drug is also aimed at “the majority of working patients, for example, who want to take part in a social meal without having to worry about traces of gluten”. However, he thinks it is unlikely that people with celiac disease will be able to eat completely gluten-free food with the transglutaminase inhibitor in the future.

Nutritionist Christian Sina sees one reason for the tough search for a drug in the fact that celiac disease can be controlled in most cases with diet - in contrast to chronic inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn's disease. In drug studies, drugs would have to show an additional benefit compared to a gluten-free diet.

Schuppan points out that about 30 percent of gluten-free patients continue to have symptoms and usually also signs of inflammation of the small intestine. "That's a very large number of patients in Germany alone," he says.

While celiac disease medications continue to be tested, over-the-counter medications are already available. DZG consultant Baas advises against this. So-called enzyme splitters are said to be able to split gluten. Since these preparations are considered dietary supplements, they do not have to be rigorously tested in studies to prove their effectiveness - in contrast to medicines.

The Charité physician Schumann would like celiac disease to be more widely recognized in society. A gluten-free diet for celiac patients should be supported by the state as therapy. "If you switch your household to a gluten-free diet, you have a very significant additional financial burden." Schumann therefore suggests that gluten-free bread be given on prescription or that those affected be given more support in other ways.

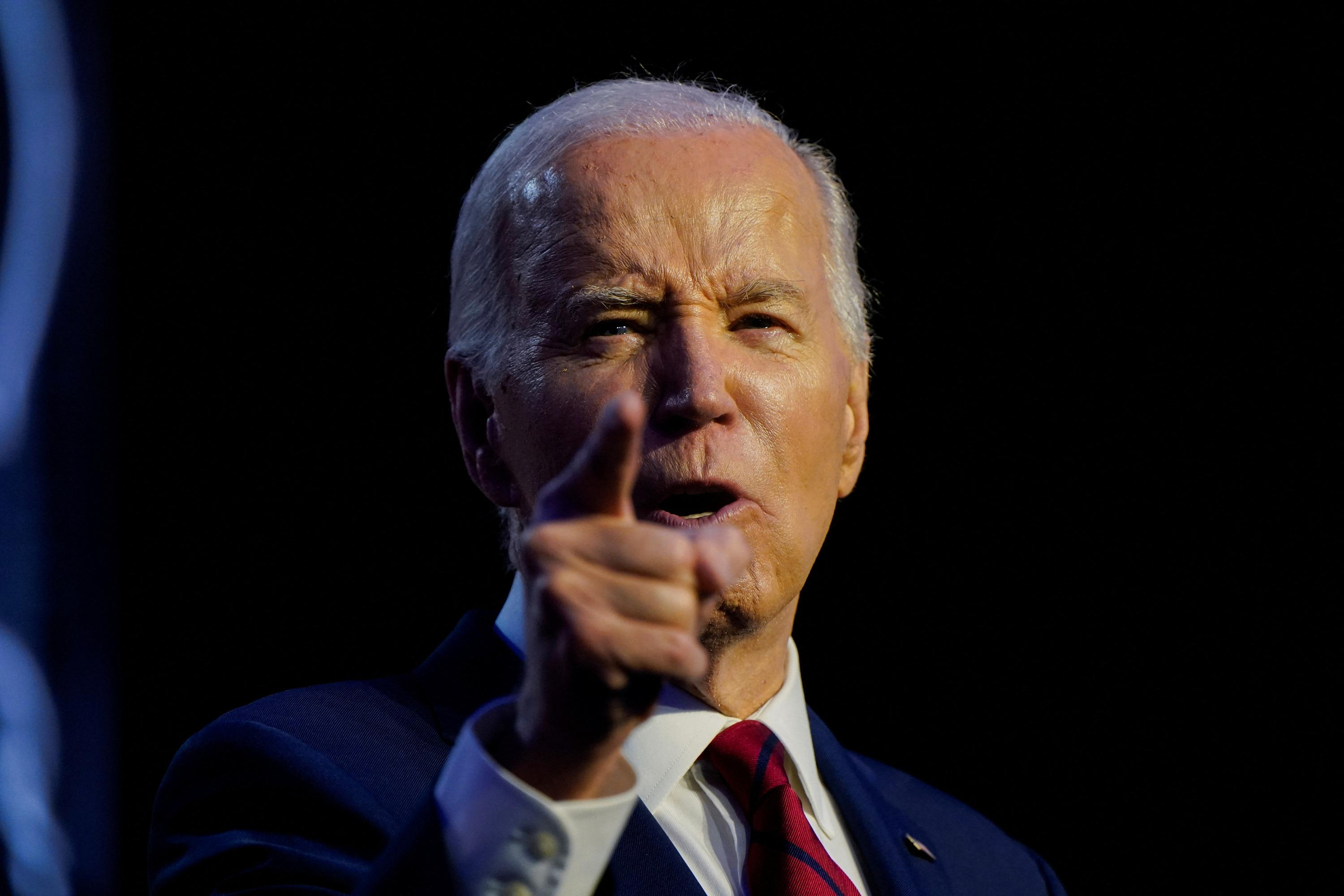

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza

Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza Israel prepares to attack Rafah

Israel prepares to attack Rafah Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Private clinics announce a strike with “total suspension” of their activities, including emergencies, from June 3 to 5

Private clinics announce a strike with “total suspension” of their activities, including emergencies, from June 3 to 5 The Lagardère group wants to accentuate “synergies” with Vivendi, its new owner

The Lagardère group wants to accentuate “synergies” with Vivendi, its new owner The iconic tennis video game “Top Spin” returns after 13 years of absence

The iconic tennis video game “Top Spin” returns after 13 years of absence Three Stellantis automobile factories shut down due to supplier strike

Three Stellantis automobile factories shut down due to supplier strike A pre-Roman necropolis discovered in Italy during archaeological excavations

A pre-Roman necropolis discovered in Italy during archaeological excavations Searches in Guadeloupe for an investigation into the memorial dedicated to the history of slavery

Searches in Guadeloupe for an investigation into the memorial dedicated to the history of slavery Aya Nakamura in Olympic form a few hours before the Flames ceremony

Aya Nakamura in Olympic form a few hours before the Flames ceremony Psychiatrist Raphaël Gaillard elected to the French Academy

Psychiatrist Raphaël Gaillard elected to the French Academy Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Archery: everything you need to know about the sport

Archery: everything you need to know about the sport Handball: “We collapsed”, regrets Nikola Karabatic after PSG-Barcelona

Handball: “We collapsed”, regrets Nikola Karabatic after PSG-Barcelona Tennis: smash, drop shot, slide... Nadal's best points for his return to Madrid (video)

Tennis: smash, drop shot, slide... Nadal's best points for his return to Madrid (video) Pro D2: Biarritz wins a significant success in Agen and takes another step towards maintaining

Pro D2: Biarritz wins a significant success in Agen and takes another step towards maintaining