Fog hangs over the valleys of the Teutoburg Forest, single swaths blow around the Lotteberg. It's a Sunday morning in autumn. Church bells can be heard in the distance. The path at the edge of the forest is deserted. Whenever a gust of wind hits the trees, the leaves fall like confetti. Ivy entwines a mighty oak. And then a cross can be seen between the trees. It's a grave cross.

If you get closer, you will discover more crosses, grave slabs, columns and bases with inscriptions. Hidden under bush and tree. Everything seems forgotten, lost in space and time. So this is the so-called forest burial ground of Halle in Westphalia, whose history began more than 200 years ago. At that time, well-to-do families had their dead buried here on the Lotteberg. The area is a bit overgrown, but accessible on narrow paths.

Old open-air cemeteries are rare. They are not to be confused with the peaceful forests or resting forests, which today offer sparsely designed burial sites under trees. Behind it are usually associations or commercial providers - in contrast to the private forest burial sites of the past. "The forest burials here in Halle are considered unique in Westphalia due to their furnishings and variety," says Katja Kosubek. The historian runs the online history museum "Haller Zeiträume". Her volunteer team has researched the stories behind most of these tombs. “Three of the forest burials are still privately owned today – the last burial on Lotteberg took place in 2021,” says Kosubek.

From the edge of the forest you can look down to Halle and see the tower of St. John's Church. Wind tears open the cloud cover here and there, always other gravestones are staged by the sun's rays. The seven small private cemeteries were laid out starting in 1811. "The cemetery on the church square in Halle was overcrowded," explains Kosubek. “On the one hand, the population was steadily increasing, on the other hand, epidemics such as tuberculosis were killing people. Half of the dead at that time were children under the age of 14.”

At that time, you had to use an iron bar, the so-called "stabber", to search for free spaces in the city's cemetery, says Kosubek. But the graves became increasingly rare. “In order to be able to bury corpses anyway, earth was carted in and piled up. Especially when it rained, the hygienic conditions were catastrophic.” Even during Prussian rule in the 18th century, burials were actually forbidden in the village and cemeteries were ordered to be built outside. A decree later reaffirmed by the Napoleonic troops. But most residents of Halle continued to use the local cemetery. "Only a few wealthy citizens such as merchants, doctors or civil servants exercised their rights as landowners, bought land outside of town and set up their family burials there," says Kosubek.

The representative facilities on the Lotteberg also show an awakening bourgeois self-confidence. "The shapes and inscriptions on the tombs reflect the thinking and feelings of this educated population group," says Kosubek. "It stands between the sober straightness of the Enlightenment and the tender feeling of Romanticism." What was new at the time was the idea that closeness to God did not have to be tied to the church, but could also be found in nature. "A burial on a sunny mountainside offered undisturbed peace, a dignified environment and the opportunity for personal expression," says Kosubek. "In contrast to the row grave in the public cemetery, there was freedom of design here - individuality, that was a completely new discovery!" It leads to a gravestone in the form of a small pyramid. On another stone is the insignia of a Masonic lodge. There is also an obelisk in the forest, on which a life-size angel once enthroned, which has long since disappeared. Instead of biblical verses, there are inscriptions like this sentence by the writer Jean Paul: "Earth life is the shell in which the core of the second life matures."

Up until the 20th century, tuberculosis was one of the most common causes of death in Germany. Friederica Heitmann, who is buried here, died of it at the age of 33, she had already lost her youngest child to this disease, her husband contracted it - and was also buried on Lotteberg. The boy August Buddeberg died of "head and heart dropsy". “The Buddebergs were enlightened, educated citizens,” Kosubek knows. "The family buried their relatives here until the 1970s."

Massive walls emerge from the undergrowth, and a wide flight of steps leads to the Vogelsang family's burial site. The gate is rusted, it squeaks when pushed open. The dark walls are overgrown with moss, lichen and ivy. Undergrowth grows in the plant. But this tomb, created in 1868, still looks representative despite its decay. Carl Dietrich Vogelsang headed the district court, "and his family's grave already shows the monumental forms of the coming empire," says Kosubek.

Katja Kosubek's team was only able to find out much of the background to the graves after painstaking archive work. For example, it came to light that the tomb with the obelisk was looted in 1921. "In the years of scarcity after the First World War, piety apparently no longer played a major role," explains Kosubek. “Zinc coffins could also be turned into money.” A grave slab has collapsed, the other slabs sound hollow. After the death of a family member in 1900, all traces of the Vogelsangs were lost.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the merchant Friedrich Wilhelm Potthoff had an octagonal pavilion built in memory of his deceased wife, perhaps it was also a mausoleum. "The Code Civil, which was based on the liberal ideas of the French Revolution, was already in force," reports Kosubek. "In the free spirit of this time, a new bourgeois ideal emerged: a family intimacy." The room is almost empty, an angel figure stands in a niche, its white glows pale, a candle burns. Katja Kosubek and her colleagues like Martin Wiegand and her father Wolfgang Kosubek suspect that there are still many secrets on the Lotteberg. A few months ago, when the storm felled some trees, the ground tore open. Fragments of another tombstone came to light - about 500 meters away from the already known graves. The work of Katja Kosubek and her team now consists of finding out the names of the dead - and telling their story.

Information and circular routes are available online at www.haller-zeitraeume.de

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza

Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza Israel prepares to attack Rafah

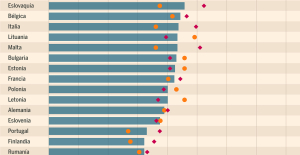

Israel prepares to attack Rafah Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Private clinics announce a strike with “total suspension” of their activities, including emergencies, from June 3 to 5

Private clinics announce a strike with “total suspension” of their activities, including emergencies, from June 3 to 5 The Lagardère group wants to accentuate “synergies” with Vivendi, its new owner

The Lagardère group wants to accentuate “synergies” with Vivendi, its new owner The iconic tennis video game “Top Spin” returns after 13 years of absence

The iconic tennis video game “Top Spin” returns after 13 years of absence Three Stellantis automobile factories shut down due to supplier strike

Three Stellantis automobile factories shut down due to supplier strike A pre-Roman necropolis discovered in Italy during archaeological excavations

A pre-Roman necropolis discovered in Italy during archaeological excavations Searches in Guadeloupe for an investigation into the memorial dedicated to the history of slavery

Searches in Guadeloupe for an investigation into the memorial dedicated to the history of slavery Aya Nakamura in Olympic form a few hours before the Flames ceremony

Aya Nakamura in Olympic form a few hours before the Flames ceremony Psychiatrist Raphaël Gaillard elected to the French Academy

Psychiatrist Raphaël Gaillard elected to the French Academy Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Archery: everything you need to know about the sport

Archery: everything you need to know about the sport Handball: “We collapsed”, regrets Nikola Karabatic after PSG-Barcelona

Handball: “We collapsed”, regrets Nikola Karabatic after PSG-Barcelona Tennis: smash, drop shot, slide... Nadal's best points for his return to Madrid (video)

Tennis: smash, drop shot, slide... Nadal's best points for his return to Madrid (video) Pro D2: Biarritz wins a significant success in Agen and takes another step towards maintaining

Pro D2: Biarritz wins a significant success in Agen and takes another step towards maintaining