Dictatorships are not the only way to lose a democracy. The old-fashioned coup d'état, for example, was not uncommon in Latin America in the last century. The rebellious military overthrows a civilian president, paralyzes Congress and censors the press. But the coup today is sometimes replaced by a contemporary hybrid regime in which an authoritarian leader comes to power through a democratic election and then subverts the system that elected him.

Brazil's current President Jair Bolsonaro is a representative of this new school. The former paratrooper, a self-confessed supporter of the 1964 military coup, secured the presidency in October 2018 in an atypical electoral process that saw both then-President Michel Temer and the leader of the main political opposition, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, elected by the candidacy were excluded. At the time, Bolsonaro received the approval of around 55 percent of the electorate. After four years in office, he is now seeking re-election.

But Bolsonaro is currently 15 percentage points behind the Labor Party's Lula da Silva, who ruled Brazil for two consecutive terms from 2003 to 2011 and who, despite a 12-year prison sentence in 2018 for corruption, is now unexpectedly allowed to stand in the elections. In 2021, Brazil's Supreme Court ruled that the trials of the former president were not conducted impartially and due process was not followed. The UN Human Rights Committee also found that Lula da Silva's political rights had been violated.

So on October 2nd, Bolsonaro and Lula da Silva will compete against each other in the election. Voting is compulsory in Brazil. The presidential election is held over two ballots; however, the winner of the first ballot is declared the winner if he already gets more than half of all valid votes - not counting blank and invalid ballot papers. Lula currently has 47 percent of the total votes, Bolsonaro is 32 percent. If the six percent of empty and invalid votes are not taken into account, the left leader comes to 51 percent, which would make a second round of voting unnecessary.

But none of that matters to Bolsonaro. The Brazilian President discredits opinion polls and the press. He also initiated an aggressive campaign against the electoral authority, which he accuses of deliberately obstructing his election campaign. In inflammatory street speeches he attacks the members of the federal court and claims that the electronic voting system in Brazil has been manipulated. Like his ally Donald Trump, he denies the facts and reacts defiantly when he doesn't like the reality.

Bolsonaro does not explicitly propagate the return of the dictatorship. Rather, he has specialized in attacking the press and journalists in the name of defending freedom of expression, promoting the annihilation of the Amazon and indigenous peoples in the name of national interest, and perverting the language of political discourse to destroy democratic institutions in the name of defending the to undermine democracy.

The scheme followed by the Brazilian President is neither original nor developed in Brazil. There are parallels, each with its own nuance, in countries as diverse and distant as Hungary, Turkey, India, the Philippines and the United States, where those in power are attempting or have attempted a cult of personality to present themselves—each in their own way—as to position the only legitimate representatives of a disgruntled popular class against the elite.

According to this version of reality, the free press, academic institutions, artists, opposition parties, non-governmental organizations, international organizations and finally the national judiciary itself are stylized as enemies of the people, and the counterbalances exercised by these institutions do not constitute legitimate manifestations of the democratic process, but merely an obstacle to the "real people" exercising their power through their designated charismatic leader.

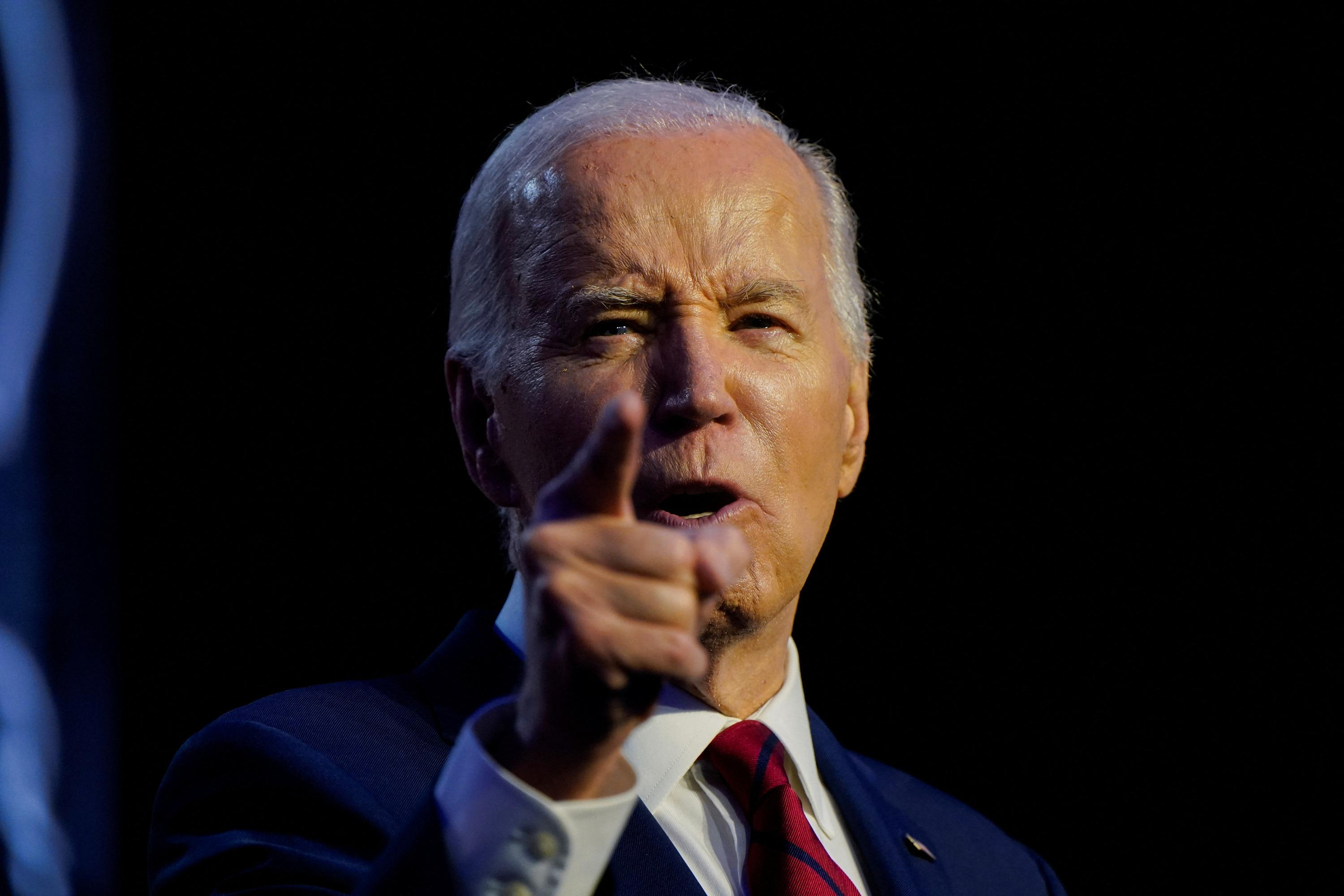

Brazil's president was among the last to formally recognize US President Joe Biden's 2020 election victory. Four weeks after the Americans voted, Bolsonaro was still saying, echoing Donald Trump's statements, that there had been "numerous cases of voter fraud." He did not provide any evidence for his statements.

During the 2018 presidential campaign and throughout his four-year tenure, Bolsonaro and some of his sons, representatives of the belligerent far-right in local politics, strove for public acknowledgment of their closeness to Trump, and in particular to his former chief strategist Steve Bannon. One of them, Eduardo Bolsonaro, MP in Brasilia, was visiting Washington on the eve of the Capitol storming. Little is known about the background of this meeting.

Autocrats and generally authoritarian figures fascinate the Brazilian president. In Europe he visits Hungary's Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and poses for photos with him. And just four days before Russia invaded Ukraine, Bolsonaro visited Vladimir Putin in Moscow and declared that Brazil "stands in solidarity with Russia".

The glorification of the Brazilian military dictatorship and its actors, the propagation of violent speech and the use of firearms, the proximity to authoritarian leaders and the attacks on the judiciary and the free press are increasing fears that Bolsonaro could certainly keep his promise to avoid an election defeat.

International pressure on Bolsonaro to respect the electoral system and voting results is vital to the survival of democracy in Brazil. It is necessary that all internationally relevant actors recognize the outcome of the election as legitimate and trustworthy and promptly acknowledge the winner, regardless of who will win the election.

It is already obvious that Bolsonaro, like Trump, is trying to obstruct the election process by spreading false news and allegations of fraud. This strategy may aim to thwart a victor other than himself. Or, as is now the case with Trump, it can only serve to perpetuate the false claim that there was no clean election defeat, but rather an outcome manipulated by the elites to prevent the populist leader from winning; and he could then dare a new attack on democracy in the near future.

James N. Green (left) is Professor of Brazilian History and Culture at Brown University and was President of the Brazilian Studies Association from 2002 to 2004. Paulo Abrão is a visiting scholar at Brown University and an advisor to the human rights organization “Article 19” for South America.

Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza

Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza Israel prepares to attack Rafah

Israel prepares to attack Rafah Indifference in European capitals, after Emmanuel Macron's speech at the Sorbonne

Indifference in European capitals, after Emmanuel Macron's speech at the Sorbonne Spain: what is Manos Limpias, the pseudo-union which denounced the wife of Pedro Sánchez?

Spain: what is Manos Limpias, the pseudo-union which denounced the wife of Pedro Sánchez? Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Private clinics announce a strike with “total suspension” of their activities, including emergencies, from June 3 to 5

Private clinics announce a strike with “total suspension” of their activities, including emergencies, from June 3 to 5 The Lagardère group wants to accentuate “synergies” with Vivendi, its new owner

The Lagardère group wants to accentuate “synergies” with Vivendi, its new owner The iconic tennis video game “Top Spin” returns after 13 years of absence

The iconic tennis video game “Top Spin” returns after 13 years of absence Three Stellantis automobile factories shut down due to supplier strike

Three Stellantis automobile factories shut down due to supplier strike A pre-Roman necropolis discovered in Italy during archaeological excavations

A pre-Roman necropolis discovered in Italy during archaeological excavations Searches in Guadeloupe for an investigation into the memorial dedicated to the history of slavery

Searches in Guadeloupe for an investigation into the memorial dedicated to the history of slavery Aya Nakamura in Olympic form a few hours before the Flames ceremony

Aya Nakamura in Olympic form a few hours before the Flames ceremony Psychiatrist Raphaël Gaillard elected to the French Academy

Psychiatrist Raphaël Gaillard elected to the French Academy Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Judo: Blandine Pont European vice-champion

Judo: Blandine Pont European vice-champion Swimming: World Anti-Doping Agency appoints independent prosecutor in Chinese doping case

Swimming: World Anti-Doping Agency appoints independent prosecutor in Chinese doping case Water polo: everything you need to know about this sport

Water polo: everything you need to know about this sport Judo: Cédric Revol on the 3rd step of the European podium

Judo: Cédric Revol on the 3rd step of the European podium