The reason was actually irrelevant. On Monday, November 4, 1968, Horst Mahler, the radical left-wing West Berlin lawyer, was due to appear before his colleagues' court of honor, which was sitting in the regional court on Tegeler Weg. He was accused of having acted as the ringleader of several hundred violent criminals from the left-wing extremist milieu at the demonstration against the Axel Springer publishing house on the evening of April 11, 1968.

Since the civil process that was actually decisive was still outstanding, it was unlikely from the outset that the court of honor proceedings would have any significant results – in the worst case, a temporary suspension of Mahler was conceivable. Even so, the radicals in the divided city were agitated.

"It was about storming the district court and freeing comrade Mahler," recalled the then 24-year-old actor and student Jens Johler. On November 1, he and a friend went to a “teach-in” at the Technical University of Berlin, where the procedure was discussed. Johler published his memories of the first days of November 1968 a quarter of a century later, in 1994, in his novel The Wrong One. The passage is a highly interesting testimony because it documents the radicalization of violent demonstrators to open terrorism.

The perpetrators wanted the dissolution of boundaries: “Equipped with construction worker helmets (against rubber truncheon blows), lemon halves (against tear gas), rainproof clothing (against water cannons) and paint eggs (for throwing) we drove to Mierendorffplatz on the morning of November 4th, where the masses were gathering should,” reported Johler. However, no “crowds” came. In fact, at most a thousand young people turned up – a small minority even of the almost 30,000 students who were enrolled in West Berlin in the winter semester of 1968/69.

At first, nothing happened. "For an eternity we stood facing each other almost immobile like two sumo wrestlers," Johler recalled. The escalation then had a cause that was never clarified: suddenly a truck with stones on the loading area rolled up to the demonstrators from behind. Where it came from, whether it was directed here consciously or by accident – all of this remained unknown.

In any case, a bombardment of stones began to fall on the officials, who wore only their traditional cardboard tin helmets (the "shakos") and raincoats. The West Berlin police did not yet have protective equipment, although in the past year and a half supporters of the "Apo" (the self-proclaimed "extra-parliamentary opposition") and the radically left-leaning Socialist German Student Union (SDS) have repeatedly demonstrated at demonstrations with stones and had thrown at others.

"I reprimanded myself and threw a paint egg," Johler recalled. "It burst on a young police officer's shako and the thin gray oil paint dripped down his face. I felt like a hero, but regretted that I didn't fill the hollow egg with red or yellow paint.” A police water cannon went into action, at the same time tear gas cartridges were fired into the air over the rioters. "I put lemon juice in my eyes and fled in the direction of Mierendorffplatz. But the brave stopped and took up the fight again, so that gradually the less brave returned and sometimes participated more, sometimes less.”

There were now heaps of gray stones in the square; Demonstrators had torn them out of the pavement. Johler wrote: "They called the stones 'arguments'" because the opponents of the SDS and Apo, but also moderate leftists, kept repeating that stones were "not arguments." “. The extremists bluntly refuted this mantra.

"After I threw my second egg, I also picked up a stone, although I wasn't particularly good at throwing it," Johler continued: "As a target I chose a rider in uniform who was swinging his baton and a comrade pursued. Now, I thought, now. The throw wasn't that bad. The stone missed the policeman's head by a hair's breadth.”

This officer was lucky, but about 130 others were not. The West Berlin police counted at least that many injured among their own people after the "Battle on Tegeler Weg", ten of them seriously, some with skull fractures. The demonstrators injured 30, none of them seriously. "More endangered than the brutal rioters were the Berlin police officers in the vicinity of the district court on Tegeler Weg," reported WELT: "They were pelted with petrol cocktails, bags of paint, but above all with bricks. The number of rioters injured in this street battle is small, the number of police officers who fell down covered in blood is large.”

Incidentally, the reason for the explosion of violence had meanwhile passed, because just as the brutality on the streets around the district court on Tegeler Weg escalated to an unimagined degree, the court of honor of the bar association in the building rejected the public prosecutor's application to revoke Mahler's license. "The violent provocateurs would have to say, if they thought it was fair and political, that this is proof of the tolerance of the legal institutions," commented WELT and concluded in bewilderment: "But they don't ask about the law."

Although 49 violent demonstrators were arrested, the Berlin public prosecutor's office applied for an arrest warrant against only one of them. The 19-year-old was accused of serious breach of the peace; several witnesses had observed him throwing stones. The rest of those arrested were released.

The official statement of the SPD-led West Berlin Senate stood in strange contradiction to this. Because the state government of the divided city appealed “to those parts of the young generation who are concerned with reforms in society” to “clearly reject terror and terrorists”. Clear words that were not followed by deeds.

The demonstrators felt empowered. Jens Johler reported on a meeting shortly after the escalation of violence back in the Audimax of the TU Berlin: “Instead of self-contrition, the loudspeakers in the Audimax erupted in jubilation, enthusiasm and euphoria. 'As of today the movement has reached a new quality,' shouted a comrade: 'We have shown that we are no longer defenseless victims of fascist state violence. We showed we can fight.'"

It was the prelude to the extreme radicalization of a tiny but murderous minority in the 1970s, represented by names such as Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, Ulrike Meinhof and, of course, Horst Mahler. On the rampage of the RAF against the rule of law. Sometimes the truth is quite simple: left-wing terrorism in Germany began with the stones thrown by the demonstrators on Tegeler Weg.

You can also find "World History" on Facebook. We are happy about a like.

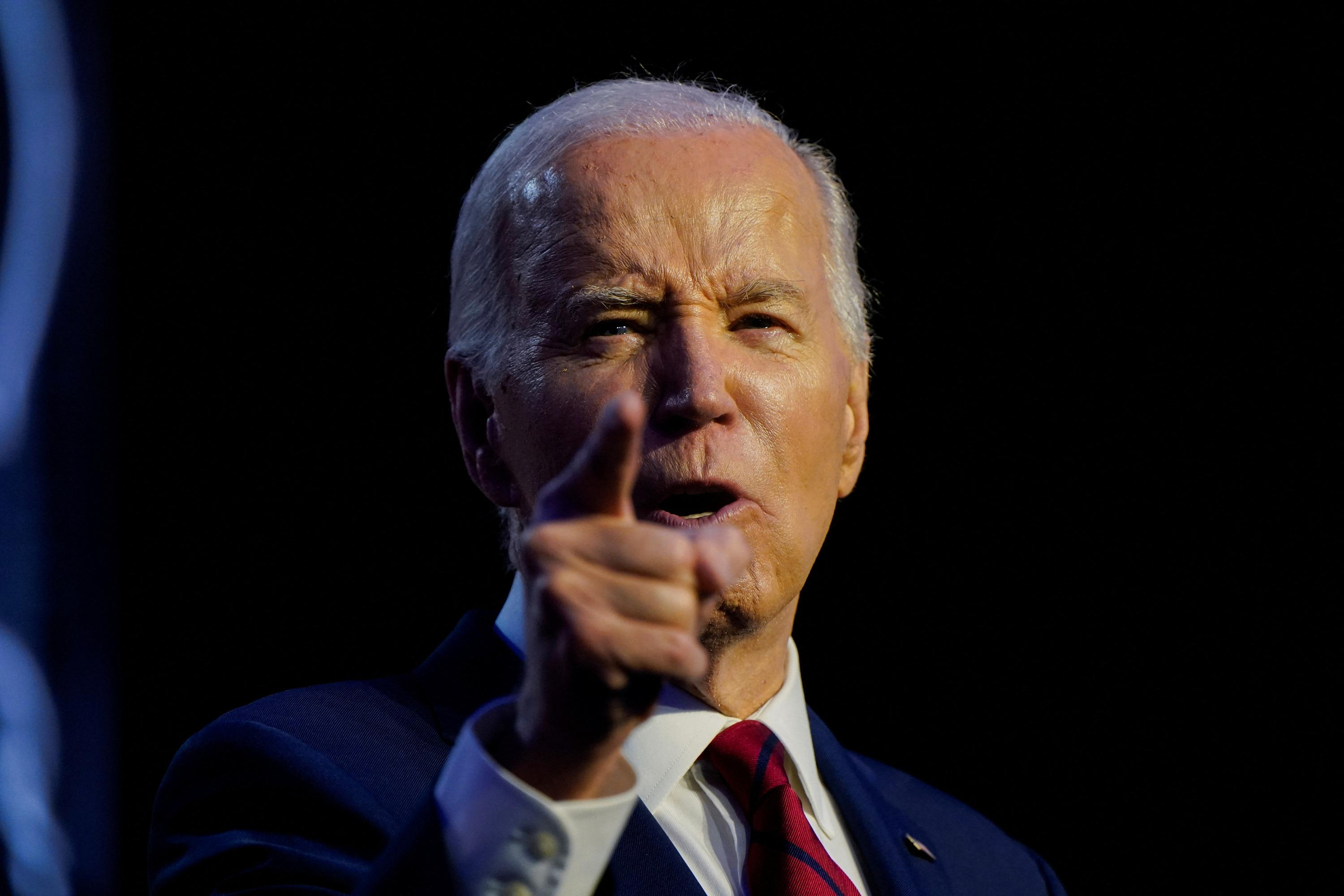

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza

Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza Israel prepares to attack Rafah

Israel prepares to attack Rafah Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Private clinics announce a strike with “total suspension” of their activities, including emergencies, from June 3 to 5

Private clinics announce a strike with “total suspension” of their activities, including emergencies, from June 3 to 5 The Lagardère group wants to accentuate “synergies” with Vivendi, its new owner

The Lagardère group wants to accentuate “synergies” with Vivendi, its new owner The iconic tennis video game “Top Spin” returns after 13 years of absence

The iconic tennis video game “Top Spin” returns after 13 years of absence Three Stellantis automobile factories shut down due to supplier strike

Three Stellantis automobile factories shut down due to supplier strike A pre-Roman necropolis discovered in Italy during archaeological excavations

A pre-Roman necropolis discovered in Italy during archaeological excavations Searches in Guadeloupe for an investigation into the memorial dedicated to the history of slavery

Searches in Guadeloupe for an investigation into the memorial dedicated to the history of slavery Aya Nakamura in Olympic form a few hours before the Flames ceremony

Aya Nakamura in Olympic form a few hours before the Flames ceremony Psychiatrist Raphaël Gaillard elected to the French Academy

Psychiatrist Raphaël Gaillard elected to the French Academy Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Archery: everything you need to know about the sport

Archery: everything you need to know about the sport Handball: “We collapsed”, regrets Nikola Karabatic after PSG-Barcelona

Handball: “We collapsed”, regrets Nikola Karabatic after PSG-Barcelona Tennis: smash, drop shot, slide... Nadal's best points for his return to Madrid (video)

Tennis: smash, drop shot, slide... Nadal's best points for his return to Madrid (video) Pro D2: Biarritz wins a significant success in Agen and takes another step towards maintaining

Pro D2: Biarritz wins a significant success in Agen and takes another step towards maintaining