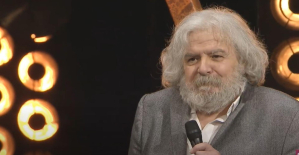

In 1960, he has occasionally said in interviews, he sat across from Mao Zedong at midnight. He had come to Beijing with a delegation of writers opposed to the US-Japan security pact, the youngest at 25.

Mao just sat there, chain smoking and talking to himself non-stop. "Suddenly, after maybe an hour, Mao stopped talking, looked at me steadily and before leaving the room said to me: 'You are young, you are poor, you are completely unknown. You will be a good revolutionary!’.”

Kenzaburō Ōe did become a poet after all, a world-renowned poet. In 1994 he was the second Japanese to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature. And, in its own way, a very revolutionary one, also from a political point of view. The militarists, nationalists and imperialists in Japan hated him because he wanted something other than subjection. For years he wrote against the rearmament of Japan, the close ties to the United States.

And again and again about the guilt Japan had shouldered in World War II, a stubborn liberal who never stopped trying to undermine the need for silence in a society that would rather forget and start over than engage in moral archeology and soul-searching.

He described his political position as that of an "anarchist who loves democracy," and his beliefs kept him from going to bars, where he frequently got into violent arguments with people who worshiped the Emperor. Of course he became something of a moral authority.

However, Ōe was never a big talker who swung speeches, climbed podiums or led signature cartels. He preferred to speak through his highly literary and form-conscious work. His novels are labyrinths of the imagination in which one can easily get lost – and therefore have to start from the beginning again and again: literary allusions, influences from existentialism (he wrote his thesis at university on Sartre), depictions of nature with great poetic power , a lot of “magical”, “surreal” and “grotesque”, as texts like to be called that do not content themselves with naturalism.

And a never-ending individualism that cares less about mediation than about making a work coherent. Now and again he almost regretted it because it cost him readers: Over the years, he once attested to himself in an interview, that his style had become “very difficult, intricate, complicated. This was necessary for me to improve my work and create a new perspective, but at some point doubts began to arise as to whether so much effort was the right method for an author".

His novels often deal with the developments in Japanese post-war society - the suffering of being an outsider, the complicated relationships between tradition and modernity, the trauma caused by history, the narrowness of bourgeois conventions, the alienation of the younger generation.

Ōe's novel A Personal Experience became best known in Germany. It tells the story of a young man whose son is born with massive brain damage. It's a book that you can hardly stand because it's so intense: episodes in which the protagonist's desperate consciousness thrashes wildly, conjures up atrocities against his newborn child, and cannot withstand the overwhelming demands of an existential misfortune.

What Ōe describes is a literary treatment of his own fate: his own son Hikari was born with a severe disability, was diagnosed by doctors as a hopeless case and did not speak a word until he was five years old - today he still needs care , but a virtuoso pianist with amazing insular musical gifts.

Unlike the father in A Personal Experience, Ōe has always loved his son unconditionally and devoted a good deal of his time to him - his life, he once said, is one third reading, one third writing and one third being with Hikari, and although he is not a believer, it is almost a religious ritual for him to tuck his son in every night.

He was once asked whether he had a happy life. Kenzaburō Ōes, affirmative, Answer: It is boring. "I've spent my life staying at home, eating the food my wife cooks, listening to music and being with Hikari. I feel like I've had a good career - an interesting one. I woke up every morning knowing I would never run out of books to read.”

Kenzaburō Ōe died on March 3rd at the age of 88, as his publisher has just announced. He was a great writer and a good person.

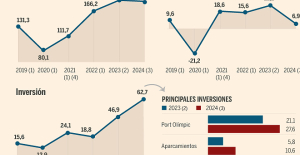

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives

War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” Irritable bowel syndrome: the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets is confirmed

Irritable bowel syndrome: the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets is confirmed Beware of the three main sources of poisoning in children

Beware of the three main sources of poisoning in children First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte

First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025

Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025 Thanks to intelligent cameras, RATP will indicate the least crowded trains on line 14

Thanks to intelligent cameras, RATP will indicate the least crowded trains on line 14 Dubai begins the transformation of Al-Maktoum to make it the future “largest airport in the world”

Dubai begins the transformation of Al-Maktoum to make it the future “largest airport in the world” When traveling abroad, money is a source of stress for seven out of ten French people

When traveling abroad, money is a source of stress for seven out of ten French people Elon Musk arrives in China to negotiate data transfer and deployment of Tesla autopilot

Elon Musk arrives in China to negotiate data transfer and deployment of Tesla autopilot Two people arrested for attempted damage to classified property at the Musée d’Orsay

Two people arrested for attempted damage to classified property at the Musée d’Orsay Death of composer Jean Musy, at 76, author of the music of Papy fait de la resistance, Les Champs-Élysées

Death of composer Jean Musy, at 76, author of the music of Papy fait de la resistance, Les Champs-Élysées Fanny Ardant prodigious in The Wound and the Thirst

Fanny Ardant prodigious in The Wound and the Thirst Hospitalized for pneumonia, Véronique Sanson cancels her concert in Nantes

Hospitalized for pneumonia, Véronique Sanson cancels her concert in Nantes Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Europeans: a senior official on the National Rally list

Europeans: a senior official on the National Rally list Blockade of Sciences Po: the right denounces a “drift”, the government charges the rebels

Blockade of Sciences Po: the right denounces a “drift”, the government charges the rebels Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Mercato: Fonseca coach of AC Milan? The Lille coach speaks

Mercato: Fonseca coach of AC Milan? The Lille coach speaks Ligue 1: OM with a three-way defense, Lens changes almost nothing

Ligue 1: OM with a three-way defense, Lens changes almost nothing Ligue 1: PSG officially crowned champion of France for the 12th time

Ligue 1: PSG officially crowned champion of France for the 12th time Ligue 1: Lyon offers Monaco and gets closer to a European place

Ligue 1: Lyon offers Monaco and gets closer to a European place