Filmmaker, producer, journalist, writer, former Minister of Culture and member of the Academy of Fine Arts, Frédéric Mitterrand has died at the age of 76. He had been battling cancer for more than a year, an illness which he had spoken publicly about.

It's sometimes difficult to make a name for yourself when you have your parents' name. For Frédéric Mitterrand, sharing the surname of his uncle François Mitterrand is more about the incident with which he knew how to play - he had to play - throughout his career. “It’s a multiplier of advantages and a multiplier of problems,” he testified in 1992 before Thierry Ardisson. There are people who become more likable, people who become less likable. But if people become more likable or less likable because of that, they are wrong. There’s no point in that.” Before managing to definitively detach oneself - literally and figuratively - from this obsessive kinship, the journey was long. The same name, the same number, an obvious connection down to certain physical features with a blatant resemblance. But also a distance suffered, maintained then claimed over the years. If François Mitterrand was ever attentive to his very large family, he did not flaunt it in his public career.

Also read Frédéric Mitterrand, his loves, his troubles, his remorse...

Frédéric Mitterrand, from his adolescence to his already advanced life as a man, lived in a family and in a France forced and then forged by his uncle. He was born the year when François Mitterrand became a minister for the first time, he was eighteen years old when De Gaulle was put on hold by the impetuous de Jarnac, thirty-three years old when he witnessed the socialist's first victory at the presidential, forty-seven years when “my uncle” ceded power. For a long time, he was reluctant to talk about this shadow that weighed him down, without ever denying its weight. And he waited for François Mitterrand to leave the Élysée to write in a book, The Years of De Gaulle, his admiration for the general and his childhood tugs at Mitterrand.

In this manifesto-testimony, Frédéric Mitterrand expresses more his human flaws than his political conscience. The text supported his commitment to Jacques Chirac's campaign; which the left saw as a betrayal, which was perceived as a defection when he himself explained that he was tired of expecting affection. The book was published in the fall of 1995, a few weeks before his uncle's death. He would defend himself by looking into the eyes of anyone who dared to mention this idea to him; then he would have moved on with that jaw-dropping smile. But Frédéric Mitterrand had two lives, one before, the other after.

The last born of Edith Cahier and Robert Mitterrand, the big brother of the former President of the Republic, Frédéric Mitterrand was born on August 21, 1947 in Paris. A child from the 16th arrondissement, the last of three boys, he concluded his schooling without incident with a coup: in the tumult of 1968, he applied for the ENA, was eligible, but did not support never oral. Not a political move, no. A story of the heart, he will apologize. The desire also not to follow in the footsteps of their ancestors: engineer, minister, soldier, elected official, the Mitterrands already give a lot to France. He launches into cinema, his passion.

Frédéric Mitterrand keeps the burning memory of a filming in which he participated, at 12 years old: Fortunat, with Bourvil and Michèle Morgan, his mother on screen. Already a rebel, he had gone alone to the auditions, alone to the tests, with his broken arm in a sling, without warning his parents. To the nerve. He had hidden his name. “Out of shyness,” he will testify to those who want to believe him. In the credits, he is credited Frédéric Robert. And he will tell his whole life how he ended up in the bed of the star actress, for the duration of a scene.

Twelve years later, in 1971, Frédéric Mitterrand responded to a classified ad and bought a cinema in Paris. Then two, then three. In a few years, he created an arthouse network, a program of classics but also of cinema from the world's screens, the likes of which were rarely seen in France. It shows Lamarr, Kurosawa, Duras, Bergman, Loach… The company is great, but the accounts leave something to be desired. After fifteen years, he decided to close his business and closed his Olympic network. He still has debts to pay off, in millions of francs.

In the meantime, the whimsical cinema director with easy interpersonal skills expands his activities without breaking with the film. He slips from behind the spotlight to behind the camera to produce Love Letters to Somalia, where a documentary on the Horn of Africa and the intimate diary of a man abandoned by his lover intertwine. His writing and his voice play the leading role. He slides from behind to in front of the camera, on TF1 then on Antenne 2, the doors of which opened at the right time after the victory of François Mitterrand. His style, which will delight comedians and imitators, contrasts with that of the cinema gentlemen to whom viewers are accustomed. A bit like with “my uncle”, we like it or we don’t like it, but it doesn’t leave many people indifferent.

In Stars and Canvases, alongside Martine Jouando, we hear her defending pell-mell, the vigor of Turkish cinema, the verismo of German production, the eternal glory of Hollywood. We discover the words of Serge Daney, Pierre-André Boutang, Jean Douchet... The left in power wanted to change television and, opportunely, Frédéric Mitterrand will be one of the faces, one of the signatures. When cohabitation and the privatization of TF1 put an end to the experiment, it was on Antenne 2 that Frédéric Mitterrand found refuge.

Long before the genre became an obligatory fixture on TV schedules, with its share of clichés, sepia-toned staging and necessarily formal tones, Frédéric Mitterrand made stars the material for a whole series of brilliant emissions. Destins, on TF1, then Étoiles and Les Amants du siècle on Antenne 2 become the ritual meetings for admiring viewers to follow the careers and lives of Brigitte Bardot, Marlene Dietrich, Grace Kelly, Elizabeth Taylor and Charlie Chaplin. He tries his hand at cultural news. It will be Midnight Permission, On Fred's Side where he welcomes Audrey Hepburn as well as Arielle Dombasle, or Étoile Palace, broadcast live from the Wagram room.

TV is changing. It becomes the kingdom of hosts-producers, shows that are dripping with money and audience ratings that have the value of life or death on the programs. Frédéric Mitterrand plays the game, even gets caught up in it, lending his skillful words to the story of the tumultuous lives of crowned heads or personalities who were not yet called people. In the stars, in the greats, in the lives of all those who have succeeded and whose name has been recorded in History, he looks for the flaws and recounts with delight the weaknesses and doubts. The emphasis of the tone, the vanity of the style can be annoying but we can guess in his nasal voice that each of these dramas resonates with his own life. This manner of sincerity means that he is never more at ease than in tragedies; he gets drunk there and takes the audience with him. In a PAF that has become very competitive, it does not seem to have the same weapons as others. However, he has a sense of spectacle: the day he received a Golden Seven for On the Side of Fred's, when the show was decided to end, he placed his trophy on the ground, "where the public service”, and turns on his heel.

As the 1990s progressed, Frédéric Mitterrand became rarer on the small screen. A past fashion effect, weariness also of the character he has constructed for himself. He maintains his network to place a program here, fulfill a mission there. But it is behind the scenes that he is now active, serving a Tunisian season, a year of Morocco, with the CNC when he chairs the advance on receipts commission. When François Mitterrand leaves the scene, Frédéric Mitterrand jumps in, as if the political landscape was not big enough for two Mitterrands. But his first are less assured than those of his illustrious elder. His love of Jacques Chirac's candidacy in 1995 came to an end. He will tell of his disappointment at having been a “name”, a prize of war in the dying Mitterrandie and promises that he will not be taken there again.

In 2003, Frédéric Mitterrand took over as director of programs for TV5, a channel which hopes to gain visibility both in France and abroad. We quickly guess that he hasn't changed - why would he? - but his plans for sparkling television quickly came up against a lack of resources. So he resumes his freelance work in the press, his radio shows, writes a column on the gay television Pink. The Élysée came back for him in 2008 to work, in an ad hoc commission, on the future of public broadcasting. Nicolas Sarkozy wants to change everything and promises to eliminate advertising. An attractive prospect for Frédéric Mitterrand, but he would only be there for a few weeks before being appointed, again by the president, director of the Villa Medici. At 60 years old, we imagine him holding his marshal's baton there. No way. Frédéric Mitterrand will only spend a few months in Rome, before being recalled by Paris in June 2009. A new mission awaits him and time is so pressing that he announces it himself, on television, the day before the reshuffle: Frédéric Mitterrand will replace Christine Albanel at the Ministry of Culture and Communication.

A Mitterrand who had supported Chirac today in the service of Sarkozy? There’s something to get everyone in Paris talking. “Sarkozy was indeed Mitterrand’s minister,” he responds point-for-tat. In Valois, the one who said no to the ENA shows himself to be diligent and technical. They thought about appointing “a mountebank” (the expression is claimed), he refused the role. For months, he battled with a cabinet that was not in his control, imposed by Matignon and the Élysée. “The beginnings were complicated. For them, appointing me was a good operation, and should be just that,” Mitterrand explained to Nouvel Obs in 2011. He inherits the minefield of the Hadopi law on digital technology, stranded projects like the Philharmonie de Paris or the Mucem of Marseille, aborted projects like the House of French History desired by Nicolas Sarkozy.

He was especially appointed on the eve of the financial crisis which would devastate the world's economies and the finances of the French state. We will have to manage the shortage until 2012. On paper, the budget has progressed, but it is mainly because we add aid to the press or the contribution to public broadcasting. The reform of the intermittent worker regime, of which François Fillon made a textbook case? Deferred. “I leave it to my successors,” he explained later, not dissatisfied. As for the major reform of cultural administrations, it will remain to be done. After the defeat of Nicolas Sarkozy and his return to civilian life, he explained that he did not have a free hand to attack the “bureaucracy” and the “unions”.

At the ministry, Frédéric Mitterrand is caught up in a controversy which has been brewing since the release of La Mauvaise Vie, an autobiographical novel in which he recounts his homosexuality. In 2005, when it was published, he had to explain his experiences in a Thai club. He had done it out of honesty, explained the writer, assuming the “ugly” and “gloomy” side. Four years later, the same pages are brandished by the FN, part of the majority and the opposition. And it is on TF1's 8 p.m. broadcast that this time the minister responds to these accusations, explains the support he has just given to Roman Polanski and defends himself from any apology for sex tourism. The controversy will never end. In 2011, he affirmed his support for the regime of Tunisian President Ben Ali, in the middle of the Arab Spring; the man who has obtained dual Franco-Tunisian nationality since the 1990s will express regret for his complacency towards the regime a few months later.

When Frédéric Mitterrand left rue de Valois in 2012, after the defeat of Nicolas Sarkozy, he was not quite finished with politics. He will retain a “tenderness” for François Fillon, who had supported him in difficult times. In 2015, he recorded, for history, a major interview with Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, the final pirouette made in Mitterrandie. But as if regrets were already affecting him, he immediately began working on a documentary devoted to the former President of the Republic's childhood in Jarnac. In 2016, after having fought severely with his successors in Culture and in particular with Aurélie Filippetti, he came out in favor of a new mandate for François Hollande, whose “results are not as catastrophic as they say”. To Nicolas Sarkozy, who had appointed him minister, he explained that he had “changed sides to come home”. He will finally become the commentator, first intrigued then disappointed, on Emmanuel Macron's five-year term. Without ever abandoning his histrionics. Weathervane, Frédéric Mitterrand? “I'm like many French people, it's not the weather vane that turns, it's the wind, as Edgar Faure said,” he claimed on France 2 in 2016.

In 2019, two new adventures await the septuagenarian. With his brother Olivier, Frédéric Mitterrand takes the helm of Christian Bourgois editions, in which the family investment fund has invested. The literary world rumbles at the announcement of this bad manner given to the venerable independent house and to Dominique Bourgois, the widow of its founder, who is leaving office. A few months later, Frédéric Mitterrand gave up his position as editorial director. At the same time, he was elected to the Academy of Fine Arts at the headquarters of Jeanne Moreau, within the Artistic Creations in Cinema and Audiovisual section. Three years after failing to enter the French Academy. When he moved in, his brothers Jean-Gabriel and Olivier, his sons Mathieu Mitterrand, Jihed Gasmi-Mitterrand and Saïd Kasmi-Mitterrand, his cousin Mazarine Pingeot were there, in the middle of the green clothes and the noble families who, for nothing, would have in the world, missed his coronation.

It was February 2020, a few days before the pandemic hit. In November, Frédéric Mitterrand took up his pen again to write A Funny War (Robert Laffont), the story of the fight led by his brother Jean-Gabriel against illness and his family's apprehensions. The gallery owner was infected at the Maastricht fair, organized at the beginning of March while the whole of Europe was closing down and France was locked in lockdown. In the diary he keeps, Frédéric Mitterrand notes his anxieties, his fears, his emotions, and the moments, too, when the absurd takes over to the point of laughter. In Normandy where he is confined, his mind wanders in front of Professor Salomon's daily updates on the epidemic situation. Didn't he see this sign language translator who accompanies him in an Almodovar, describing, with many gestures, a horrible murder? And what about these “cities without cafes, without cinemas, without theaters, without public gardens, without transport, with mostly closed shops and deserted streets”? Is this “a Houellebecq nightmare”? His brother, after critical weeks, will recover. He too will find himself changed. Amid reflections that flirt with surrealism, Frédéric Mitterrand writes: “The virus is like everyone else. He will recover his health next summer, enjoying the beaches, festive aperitifs and weddings. He will come back all refreshed from his good vacation to launch the second wave.” Like a pythia, drunk on tragedy.

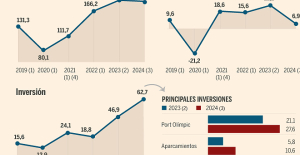

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives

War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” Irritable bowel syndrome: the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets is confirmed

Irritable bowel syndrome: the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets is confirmed Beware of the three main sources of poisoning in children

Beware of the three main sources of poisoning in children First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte

First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025

Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025 When traveling abroad, money is a source of stress for seven out of ten French people

When traveling abroad, money is a source of stress for seven out of ten French people Elon Musk arrives in China to negotiate data transfer and deployment of Tesla autopilot

Elon Musk arrives in China to negotiate data transfer and deployment of Tesla autopilot Patrick Pouyanné, CEO of TotalEnergies, is very reserved about the rapid growth of green hydrogen

Patrick Pouyanné, CEO of TotalEnergies, is very reserved about the rapid growth of green hydrogen In the United States, a Boeing 767 loses its emergency slide shortly after takeoff

In the United States, a Boeing 767 loses its emergency slide shortly after takeoff A charred papyrus from Herculaneum reveals its secrets about Plato

A charred papyrus from Herculaneum reveals its secrets about Plato The watch of the richest passenger on the Titanic sold for 1.175 million pounds at auction

The watch of the richest passenger on the Titanic sold for 1.175 million pounds at auction Youn Sun Nah: jazz with nuance and delicacy

Youn Sun Nah: jazz with nuance and delicacy Paris Globe, a new international theater festival

Paris Globe, a new international theater festival Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar MLS: new double for Messi who offers victory to Miami

MLS: new double for Messi who offers victory to Miami PSG-Le Havre: Ramos on his way, Kolo Muani at the bottom of the hole… Favorites and scratches

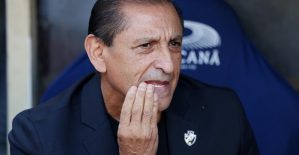

PSG-Le Havre: Ramos on his way, Kolo Muani at the bottom of the hole… Favorites and scratches Football: Vasco da Gama separates from its Argentinian coach Ramon Diaz

Football: Vasco da Gama separates from its Argentinian coach Ramon Diaz F1: for the French, Ayrton Senna is the 2nd best driver in history ahead of Prost

F1: for the French, Ayrton Senna is the 2nd best driver in history ahead of Prost