Meadows and fields, tractors and cows - despite the great importance of industrial agriculture, the profession of farmer is still considered to be close to nature. In fact, agriculture is lagging behind when it comes to climate protection. So far there have been hardly any strategies for more climate protection in agriculture, although the sector is responsible for at least ten percent of CO₂ emissions in the EU. In Germany, according to the Federal Environment Agency, it is around seven percent.

Politicians have big plans for agriculture in terms of climate policy: in future, farmers should play a central role in ensuring that the EU achieves its climate goals. In 2050, the continent should operate in a climate-neutral manner. This means that no additional greenhouse gases should then be released into the atmosphere from the EU.

Mind you, politicians are talking about climate neutrality and not about not releasing any greenhouse gases at all. Because despite all the technical progress, greenhouse gases will still be blown into the air in 2050. Cattle, for example, will still emit methane, although possibly less due to dietary changes. It may also be technically impossible to replace fossil fuels in some industrial processes.

Until then, there must therefore be ways of systematically removing CO₂ from the air and locking it up in the long term. Technical sequestration (CCS), in which CO₂ is captured and stored in underground storage facilities, is still expensive. Additional forests can also store carbon dioxide, but forest areas are currently decreasing.

That is why politicians rely on so-called carbon farming. In a narrower sense, farmers harvest climate-damaging carbon dioxide from the air and sink it into the ground. To do this, fields have to store more CO₂ than before, primarily by building up more humus in the soil.

For example, mustard, oil radish or similar plants can be grown between two harvests, which rot in the field and are then worked under. Certain plants, such as legumes, also direct CO₂ into the soil. And by using special machines and techniques, farmers can avoid the deep plowing of fields, which normally releases carbon.

Carbon farming is a central part of the European Green Deal by Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission. "Agriculture and forestry play a central role in achieving our climate protection goals," said Federal Minister of Agriculture Cem Özdemir (Greens) recently. The federal government and the EU are banking on paying farmers for the carbon harvest.

It is to be financed via a certificate trade. The farmers register the corresponding fields from which soil samples are taken in order to measure the carbon content, for example. It is then up to the farmers to decide which carbon sequestration methods they want to use. Later they have to measure again how much more carbon is in the soil.

Appropriate certificates are then issued for the stored CO₂, which the farmers can sell, for example to industrial companies, which use them to compensate for their own CO₂ emissions. The value of the stored carbon should be based on the CO₂ price in emissions trading. It is currently 85 euros per tonne of CO₂.

However, the market for CO₂ compensation, for example with airlines, is hardly regulated; there is a regularly criticized wild growth and there are many cases of fake climate protection, so-called greenwashing. The European Commission has therefore made suggestions as to what the certification should look like. Those affected have been able to comment on the proposal since last week. Then the European Parliament and the Member States still have to agree and can still change the law in the course of the procedure.

Although the authority wanted to create clarity with its proposal, it did not manage it, according to the judgment of the non-profit environmental think tank Ecologic. On behalf of the Federal Environment Agency, their experts looked at the Commission's proposal and found many unanswered questions.

Above all, the proposals were too vague for the experts. "The Commission's proposals do not define how the certificates are to be used in the first place," says Aaron Scheid, co-author of the analysis. "It remains unclear whether farmers can sell the certificates to industry so that they can offset their own CO emissions or whether they should only be used to offset emissions within agriculture." It is also possible that they could be traded in Europe with pollution certificates (ETS).

It is also questionable whether carbon farming is worthwhile for farmers at all. According to co-author Aaron Scheid, it can only be reliably determined after at least 25 years whether a farmer has successfully harvested CO₂. “Soils do not absorb detectable amounts of CO₂ overnight. It takes 25 to 30 years for CO₂ to accumulate significantly in soil,” says carbon farming expert Scheid. "These processes in the soil are very slow."

This would mean that farmers would not be compensated for their efforts for decades. Annual measurements are unrealistic anyway, says the expert. The analyzes are expensive and there are not enough experts and capacities to examine soil samples every year.

Even if bound CO₂ can be quantified after many years, it remains completely unclear how long the bound CO₂ will remain in the soil. It actually takes 300 to 1000 years. However, the carbon is not very firmly bound in the soil and can be quickly released again at any time.

For example, the farmer can return to intensive use. But extreme drought and dryness or persistent heavy rainfall could also quickly release carbon stored in the soil. In view of the climate development in recent years, these are possible scenarios.

"Warmer temperatures are expected to accelerate the natural degradation rates of humus in our soils and thereby reduce humus levels," summarizes Carsten Paul, carbon farming expert at the Leibniz Center for Agricultural Landscape Research (ZALF). "Presumably, farmers will need to use all their skills and experience to prevent their soils from losing stored carbon and becoming sources of greenhouse gases."

Scheid warns that the difficulties in reliably measuring CO₂ binding and the lack of clarity about how long it will remain in the soil make carbon farming with certificates a real climate risk. "If we cannot ensure over long periods of time that CO₂ is really being bound in the soil and also cannot determine how long it is stored, it would be risky to sell CO₂ certificates to compensate for greenhouse gas emissions elsewhere," says sheath

"If the buyer of the certificates believes that they are compensating and continue to produce the corresponding amount of CO₂, but at the same time no CO₂ has been bound or it escapes again, ultimately even more CO₂ will be released than if there had been no certificate at all."

Farmers could be paid for storage, but under no circumstances should the allowances be used to offset emissions elsewhere. A major study published in January by five leading agricultural research institutes also fundamentally rejects the certificates.

Storing more CO₂ in the soil is desirable, but the so-called humus certificates are unsuitable as an instrument for climate protection. Above all, there is no guarantee that carbon will be stored permanently and that permanent storage will be adequately monitored, the study says.

Researchers from the Leibniz Center for Agricultural Landscape Research (ZALF), the Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research (UFZ), the Research Institute for Organic Farming (FIBL), the Thünen Institute and the Technical University of Munich were involved in the study. "Money to combat climate change should therefore be used more effectively elsewhere," they write. "Ideally to avoid emissions."

"Everything on shares" is the daily stock exchange shot from the WELT business editorial team. Every morning from 7 a.m. with our financial journalists. For stock market experts and beginners. Subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Amazon Music and Deezer. Or directly via RSS feed.

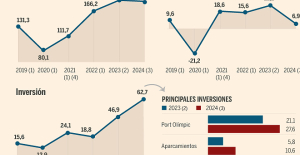

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives

War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” Irritable bowel syndrome: the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets is confirmed

Irritable bowel syndrome: the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets is confirmed Beware of the three main sources of poisoning in children

Beware of the three main sources of poisoning in children First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte

First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025

Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025 When traveling abroad, money is a source of stress for seven out of ten French people

When traveling abroad, money is a source of stress for seven out of ten French people Elon Musk arrives in China to negotiate data transfer and deployment of Tesla autopilot

Elon Musk arrives in China to negotiate data transfer and deployment of Tesla autopilot Patrick Pouyanné, CEO of TotalEnergies, is very reserved about the rapid growth of green hydrogen

Patrick Pouyanné, CEO of TotalEnergies, is very reserved about the rapid growth of green hydrogen In the United States, a Boeing 767 loses its emergency slide shortly after takeoff

In the United States, a Boeing 767 loses its emergency slide shortly after takeoff A charred papyrus from Herculaneum reveals its secrets about Plato

A charred papyrus from Herculaneum reveals its secrets about Plato The watch of the richest passenger on the Titanic sold for 1.175 million pounds at auction

The watch of the richest passenger on the Titanic sold for 1.175 million pounds at auction Youn Sun Nah: jazz with nuance and delicacy

Youn Sun Nah: jazz with nuance and delicacy Paris Globe, a new international theater festival

Paris Globe, a new international theater festival Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar MLS: new double for Messi who offers victory to Miami

MLS: new double for Messi who offers victory to Miami PSG-Le Havre: Ramos on his way, Kolo Muani at the bottom of the hole… Favorites and scratches

PSG-Le Havre: Ramos on his way, Kolo Muani at the bottom of the hole… Favorites and scratches Football: Vasco da Gama separates from its Argentinian coach Ramon Diaz

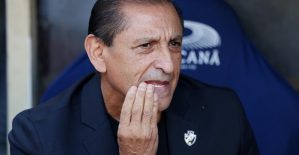

Football: Vasco da Gama separates from its Argentinian coach Ramon Diaz F1: for the French, Ayrton Senna is the 2nd best driver in history ahead of Prost

F1: for the French, Ayrton Senna is the 2nd best driver in history ahead of Prost