When Izkia Siches had been in office for just four days, one of her first trips took her to the troubled province of La Araucanía. But the Chilean interior minister was greeted with roadblocks, shots in the air and other threats by representatives of the indigenous people, the Mapuche, to her horror.

There was no sign of enthusiasm for the new, left-wing movement, for which Interior Minister Siches stands. This bitter anecdote from the early days of Chile's new government in March was a portent of what was to come for the government around former student leader and current President Gabriel Boric (36).

Neither the Mapuche in La Araucanía nor the Chilean electorate as a whole apparently want to be "re-educated" by the government in Santiago. The nationwide vote on the draft constitution, which took months to develop and for which 155 delegates were elected to a convention, failed. With 62 percent, almost two-thirds rejected the draft, plunging the Boric government into a serious crisis. More than 13 million of the roughly 15 million Chileans eligible to vote took part in the referendum.

However, the draft was controversial from the start, also because of the planned rights for the indigenous people. The indigenous people make up about 13 percent of the population of the South American country. They should be given greater autonomy and their own jurisdiction.

The 178-page draft for a "social and democratic constitutional state" also provided for the right to abortion and for environmental protection to be anchored in the constitution. For the first time, social rights such as the right to education, health and clean water should be guaranteed. Public offices should be filled equally by women and men.

The old constitution, which dates from the time of the military dictatorship (1973-1990), remains in force for the time being. While the frustrated left-wing camp is blaming a right-wing fake news campaign, President Boric reacted more confidently. "The Chilean people were not satisfied with the draft presented by the Constitutional Convention and therefore decided to clearly reject it at the polls," he said in an address from the presidential palace.

There are many reasons for failure. The Argentine newspaper Clarin commented: "The Boric camp has forgotten that Chile actually has a moderate society." Chile's economy, actually always a little more successful and innovative than that of the rest of South America, is in troubled waters.

While the constitutional convention debated undoubtedly important aspects such as gender equality, inclusion and diverse nationalities, the highest inflation rate in 28 years, at more than 13 percent, is eroding the prosperity of the middle class and driving the poor into even greater misery.

For the young population, who are actually the drivers of social change in recent years, completely different issues are suddenly important, especially the question of how they should finance their lives. In this situation, giving the country an operating system with a partly socialist orientation was obviously too much for most.

In addition, the government has misjudged the situation in the regions where angry indigenous people are opposed to the government: the Mapuche, who fundamentally do not want any white government - not even a left-wing one - to dictate their living conditions, have a much more far-reaching agenda. They want to regain the land where their ancestors lived, bitter as that is for the multicultural constitutional dreams of the Chilean left.

The fact that a radical Mapuche leader was arrested a few days before the vote on the constitution, apparently on orders from Interior Minister Siches, was an expression of helpless despair in the face of the ongoing violence. While still in opposition, the left had always criticized conservative President Sebastián Piñera's crackdown on the Mapuche leaders, who last ruled from 2018 to 2022 - now they are apparently resorting to the same means.

The consequence: in the troubled province of La Araucanía, where many Mapuche people live and where churches, trucks and forestry operations regularly go up in flames after arson attacks, people want to know even less about the "woken" constitution than in the rest of the country: the rejection was even here at 74 percent. A debacle for President Boric, who is now likely to dismiss his interior minister.

The failure of the draft is likely to have consequences beyond Chile's borders. In Colombia, the new and first left-wing President Gustavo Petro is said to want to strive for constitutional reform at some point. After three weeks in office and a wave of violence that cost the lives of police officers and social activists, Petro also had to learn painfully: Knowing better for years does not mean being able to do everything better than your conservative predecessors right away.

Colombia's president will learn lessons from Chile's reality shock. The result is also likely to have an impact on neighboring Argentina. There, however, more as an incentive for the emerging, still young liberal market movement.

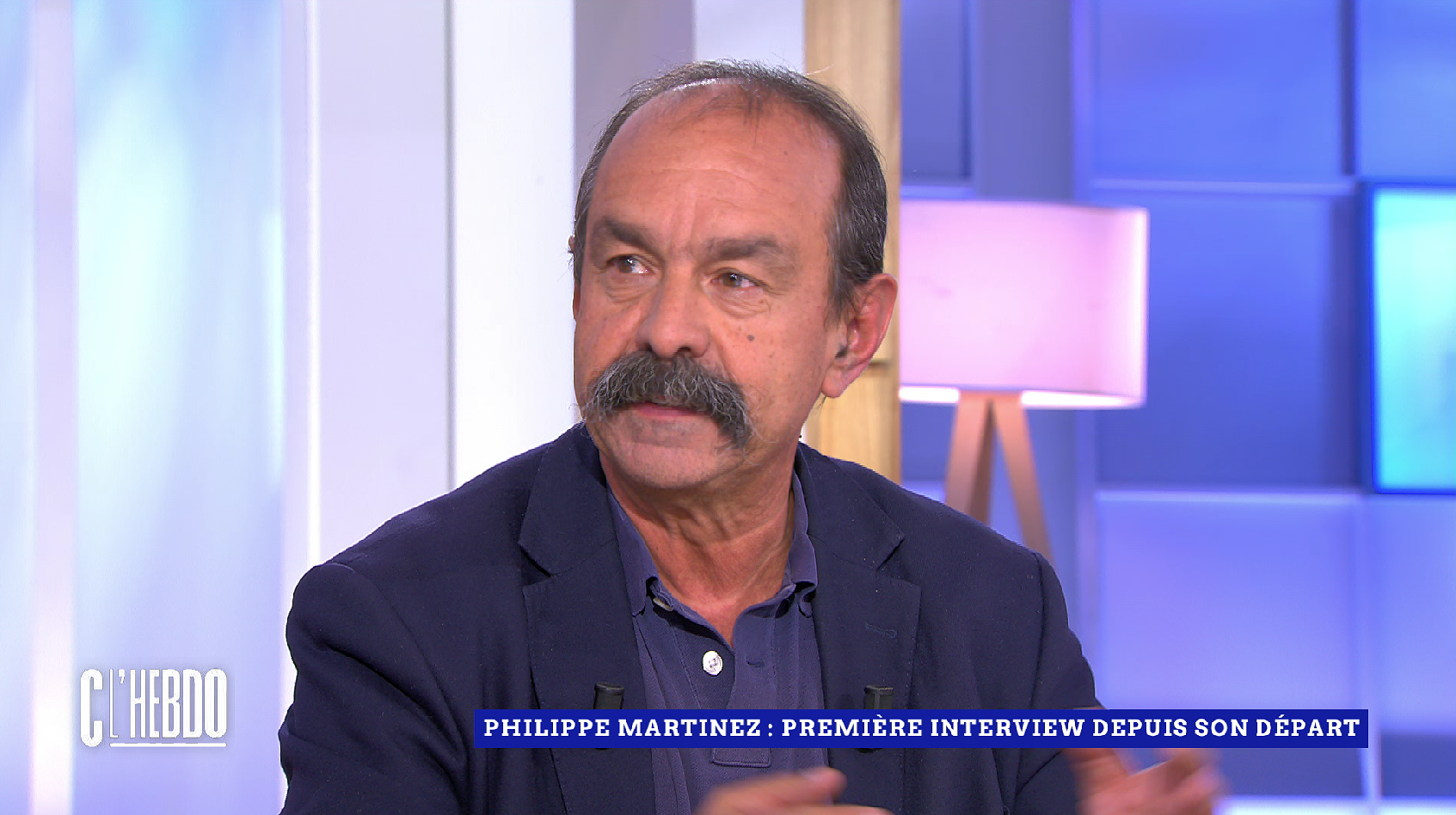

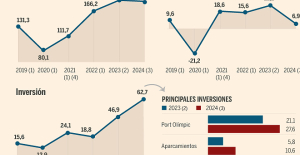

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives

War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” Irritable bowel syndrome: the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets is confirmed

Irritable bowel syndrome: the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets is confirmed Beware of the three main sources of poisoning in children

Beware of the three main sources of poisoning in children First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte

First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025

Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025 In the United States, a Boeing 767 loses its emergency slide shortly after takeoff

In the United States, a Boeing 767 loses its emergency slide shortly after takeoff The A13 motorway will not reopen on May 1

The A13 motorway will not reopen on May 1 More than 1,500 items for less than 1 euro: the Dutch discounter Action opens a third store in Paris

More than 1,500 items for less than 1 euro: the Dutch discounter Action opens a third store in Paris 100 million euros in loans, water storage, Ecophyto plan… New measures from the executive towards farmers

100 million euros in loans, water storage, Ecophyto plan… New measures from the executive towards farmers Books poisoned with arsenic present in French libraries

Books poisoned with arsenic present in French libraries New York justice returns 30 works of art looted from Cambodia and Indonesia

New York justice returns 30 works of art looted from Cambodia and Indonesia Les Galons de la BD dedicates War Photographers, a virtuoso album on the Spanish War

Les Galons de la BD dedicates War Photographers, a virtuoso album on the Spanish War Theater: Kevin, or the example of an academic failure

Theater: Kevin, or the example of an academic failure Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar PSG: “Immense pride in continuing the adventure in Paris”, relishes Zaire-Emery

PSG: “Immense pride in continuing the adventure in Paris”, relishes Zaire-Emery Breaking: everything you need to know about this sport

Breaking: everything you need to know about this sport NBA: Lakers gain respite, Boston responds to Miami

NBA: Lakers gain respite, Boston responds to Miami Top 14: “a very severe red card”, estimates Labit (French Stadium)

Top 14: “a very severe red card”, estimates Labit (French Stadium)