He has fans all over the world - and some still don't know that Georges Simenon (1903 to 1989), who created one of the most famous detective characters with Inspector Maigret, was not French at all, but a French-speaking Belgian - from Liège or Liege. It is true that Simenon moved to Paris in 1922, at the age of 19, soon traveled all over the world and also lived in America. And admittedly, Inspector Maigret solves most of his 75 cases on the Seine.

But the few crime novels that Simenon set in his hometown on the Maas (French: Meuse) are among the most interesting of his work. 'Maigret im Gai-Moulin' (formerly published as 'The Dancer' and 'Maigret and the Spy') is a wonderful example. It is halfway through the book before Maigret even makes an appearance. Before that, a whole world has opened up around the once eponymous hostess of a nightclub and two youngsters who live beyond their means.

Simenon grew up in the Outremeuse (“beyond the Meuse”) district of Liège. Here he trained his eye for social classes and their subtle gradations. At the age of 16 he was already writing for the newspaper. At the "Gazette de Liège" he was responsible, among other things, for accidents and crimes. "I had to call the six police stations in Liège twice a day to make sure there were no incidents worth mentioning." Every day at eleven, Simenon went to the basement of the town hall, where the main police station was located. A plaque provides information that a real Monsieur Maigret was on duty there. (Later, a neighbor of Simenon in Paris also had the same name. Like any literary figure, Maigret draws on a variety of sources.)

Simenon's feeling for people was clearly shaped by his journalistic work on the so-called mixed reports (“Faits Divers”). He can vividly characterize people from wealthy and less wealthy backgrounds in two or three sentences. Sometimes Simenon's settings read as if Balzac, the poet of the "Comédie humaine", and Bourdieu, the great sociologist who taught the subtle differences, had arranged to meet for the "True Crime" podcast.

Liège, which can be reached from Cologne in a good hour by Thalys or ICE, offers a suitable backdrop of appearance and reality, chic and dingy, elegant and broken people for every form of private Simenon fan fiction. The city combines horrific 20th-century building blunders and 21st-century gleaming futuristic architecture (the new train station by star architect Salgado Calatrava), with monstrous construction frenzy reinstalling a tram network that was only shut down a few decades ago. This is also – in terms of urban development – a comédie humaine.

In Liège you will find taverns where Romanians and Moroccans play cards in a happily analogous way, waiters are ironically called Kevin – and unexpectedly elegant, low-cut ladies of advanced age applaud it with shining eyes when a Kir Royal is ordered at the next table. In short: the plot of an as yet unwritten "Maigret" could begin here. The Simenon Spring (“Printemps Simenon”) has just taken place, a festival with readings, films, lectures and exhibitions. The fact that the city of Liège has recently been focusing more intensively on its most famous son, without any reason for a milestone anniversary, can be read as a literary tourism offensive.

Simenon's sociological view of people and milieus is shown in a photo exhibition worth seeing. Under the title "Simenon. Images d'un monde en crise. Photographies 1931-1935” the Museum Grand Curtius (until August 27) is presenting the novelist as a photo reporter. Simenon, who was successful early on with his trivial and crime novels, traveled to France, Belgium and the Netherlands on behalf of magazines (and with his wife and maid or lover). He also visited Germany, Poland, Lithuania, Bulgaria, Romania and today's Ukraine, as well as Georgia and Turkey. Simenon stayed in Congo for two months in 1932 (captured by the colonial perspective of his time), and in 1935 he undertook a trip around the world - with stops in New York, Panama, Ecuador and Tahiti. Around 3000 photos of his Rolleiflex and Leica have survived, around 150 are shown in the exhibition, which does not show a photographic artist, but a documentarist.

People can be seen in almost all of the pictures. Bathing in Odessa, begging in Warsaw, unloading cargo in a port – in general, people who work on canals and in boats often live and reside. Simenon himself had a houseboat with the cute name of L'Ostrogoth - the Ostrogoth. Again and again one sees poor figures, common in Europe in the 1930s. Motifs such as an eerie gas mask election poster for the Belgian Rexists or the eyes of children in the Vilnius shtetl remind us today's viewers of how fascism and the Holocaust soon destroyed an entire world, "un monde en crise".

Simenon was a frequent and fast writer. Besides 75 "Maigrets" he left more than 100 other novels, known in the scene as "Non-Maigrets". Rarely longer than 150 or 200 pages, his books provide precisely the kind of diversion befitting the miscellany of miscellany that filled newspapers during Simenon's lifetime - and social media channels today. The new “Parcours Simenon” in Liège is recommended as an entertaining excursion into Simenon’s real urban planning timeline – a smartphone app that Georges Simenon’s son was personally present in Liège to launch.

Born in 1947, John Simenon, who brokered rights and licenses for major Hollywood film studios for many years, has been taking care of his father's work since 1995. During small talk in Liège's old butcher's shop, which now serves as a tourist office, he lets it be known: According to absolute sales figures, Georges Simenon still has the most fans in Italy to this day. The total circulation in its original language, French, only came second. Depending on the current new edition, English and German shared third place. Six years ago, the news caused a stir that Diogenes Verlag had lost the lucrative Simenon rights. WELT revealed at the time that John Simenon had come to an agreement with publisher Daniel Kampa. Since 2018, Simenon's complete works have been published in revised German translations by Kampa and Hoffmann und Campe.

To this day, reading a Simenon novel, and possibly even one set in Liège, has something of the feel of a visit to a Belgian brasserie: immerse yourself for an hour or two. The ambience: rather slightly shabby than too chic. The food: down to earth, the alcohol: flowing. The women: interesting. In Simenon, people in general are rarely brilliant, rather trivial, but never boring or banal. Simenon, this “Balzac without lengths”, as a fellow French writer once dubbed him, is becoming more vivid as a photographer and reporter of social issues in Liège than he has been for a long time.

“Simon. Images of a world in crisis. Photographs 1931-1935“. Lüttich, Museum Grand Curtius, bis 27. August.

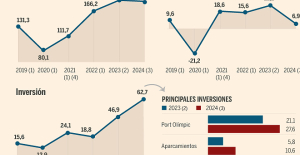

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives

War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte

First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025

Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025 Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 The A13 motorway will not reopen on May 1

The A13 motorway will not reopen on May 1 More than 1,500 items for less than 1 euro: the Dutch discounter Action opens a third store in Paris

More than 1,500 items for less than 1 euro: the Dutch discounter Action opens a third store in Paris 100 million euros in loans, water storage, Ecophyto plan… New measures from the executive towards farmers

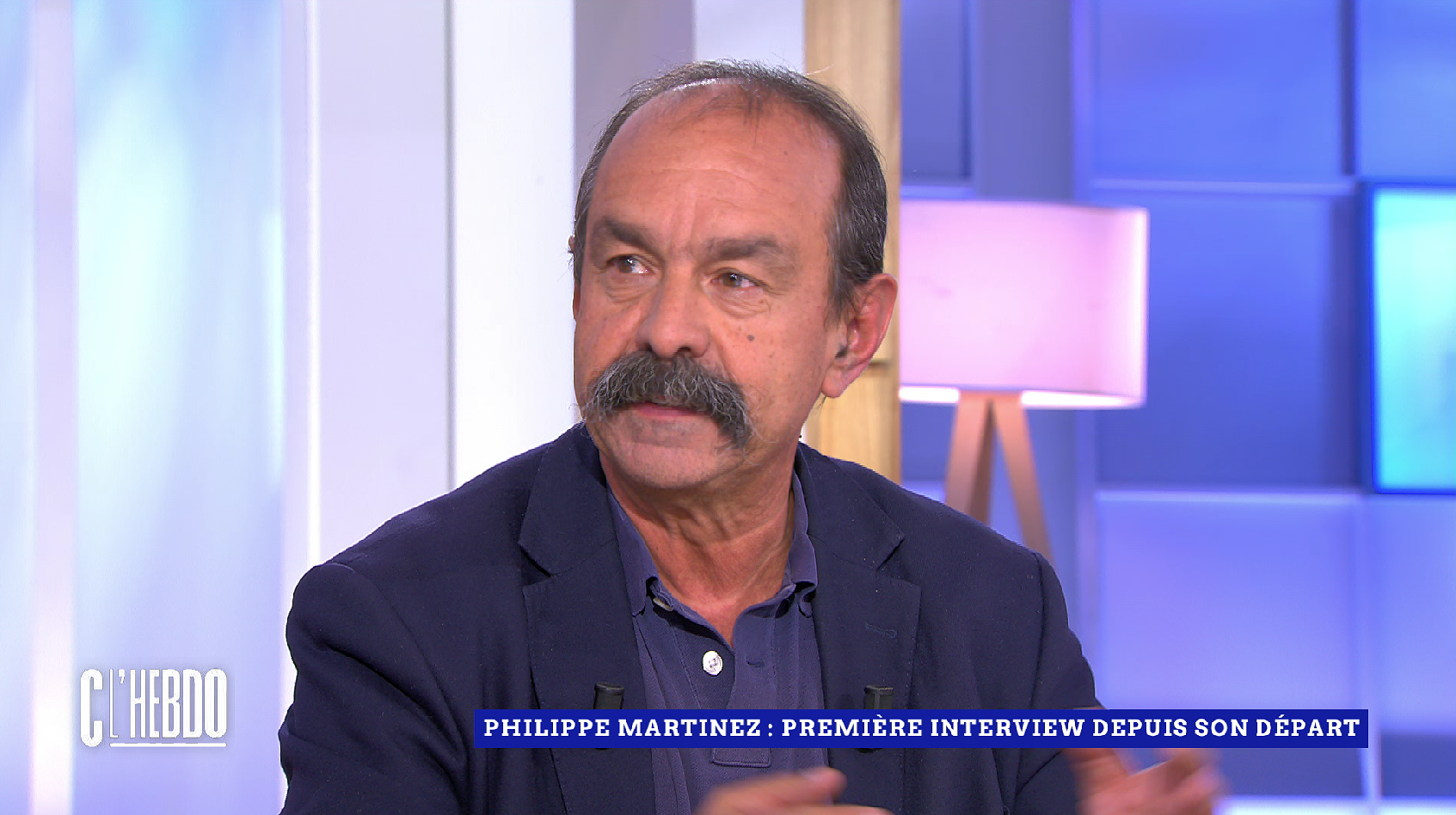

100 million euros in loans, water storage, Ecophyto plan… New measures from the executive towards farmers “He is greatly responsible”: Philippe Martinez accuses Emmanuel Macron of having raised the RN

“He is greatly responsible”: Philippe Martinez accuses Emmanuel Macron of having raised the RN Les Galons de la BD dedicates War Photographers, a virtuoso album on the Spanish War

Les Galons de la BD dedicates War Photographers, a virtuoso album on the Spanish War Theater: Kevin, or the example of an academic failure

Theater: Kevin, or the example of an academic failure The eye of the INA: Jean Carmet, the thirst for life of a great actor

The eye of the INA: Jean Carmet, the thirst for life of a great actor The Nuc plus ultra: St Vincent the Texane and Neil Young the return

The Nuc plus ultra: St Vincent the Texane and Neil Young the return Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Paris 2024 Olympic Games: “It’s up to us to continue to honor what the Games are,” announces Estanguet

Paris 2024 Olympic Games: “It’s up to us to continue to honor what the Games are,” announces Estanguet MotoGP: Marc Marquez takes pole position in Spain

MotoGP: Marc Marquez takes pole position in Spain Ligue 1: Brest wants to play the European Cup at the Stade Francis-Le Blé

Ligue 1: Brest wants to play the European Cup at the Stade Francis-Le Blé Tennis: Tsitsipas released as soon as he entered the competition in Madrid

Tennis: Tsitsipas released as soon as he entered the competition in Madrid