When it became known at the beginning of September last year that the pianist Lars Vogt had died of cancer and was just 51 years old, it suddenly became very quiet in the loud machine room of classical music. Not because cancer, that lousy traitor, had taken someone's life prematurely again, that too, above all it was very quiet because he had brought Lars Vogt.

And everyone in that engine room was suddenly sad and a little jealous of those gods he was about to play for. Gods who had blessed him with the gift of friendship, the gift of making music from notes in an almost magical, above all completely unpretentious way, breathing, living music and illuminating all its dimensions like no other.

Who made music in such a way that it always fostered a conversation and a communion, a friendship between those who wrote it, those who played it and those who heard it.

In February 2021, Lars Vogt, cellist Tanja and violinist Christian Tetzlaff met in the studio. They wanted to record Schubert's late piano trios. That was nothing unusual. The three, who played like siblings that are rare in real life, listening to each other, letting each other go first, carrying each other, deepening, had known each other for decades.

Had more or less just recorded Brahms' piano trios. Schubert's colossal trio in E flat major, a swan song, was written in the year of the "Winterreise", in the last year of his life when Schubert must have suspected how fatally ill he was with syphilis, printed after his death in November 1828, was in a live -Recording from 2005 long ago.

When the recordings started, Lars Vogt felt strange. Something was wrong. He was in pain, had to lie down after each session. While listening to the tapes of the second movement, one of the saddest, most comforting movements in the entire history of music, a "sigh that wants to increase to the point of heartbreak" (Robert Schumann), it seemed to him that he wrote in a chat that his entire life developed in a straight line towards this E flat major trio.

He wrote that he cried through the Andante con moto, just as he heard it in the studio. He is guaranteed not to be alone in this. Anyone who does not grab their tissue box during this funeral march, which is about everything, beauty and transience, during this existential winter journey in ten minutes, or at least looks strangely touched somewhere upstairs in order to avoid tears, should be unfriended as soon as possible – which Lars Vogt would certainly have found strange as a procedure.

Then came the diagnosis. Then came the chemo. And everything seemed to be going well. In June they recorded – the doctors probably didn't think it too well – the B flat major Trio, written almost at the same time as the E flat major Trio, the Arpeggione Sonata, written in 1824 for the forgotten Arpeggione and nowadays mostly performed with cello Rondo and the Notturno, Op. 148, a nocturnal, haunted drama from a piano trio movement which, like the E flat major trio's Andante con moto, leaves one somewhat stunned after it has whispered out moonlit.

Works are collected on the double CD published by Ondine, which was written by someone who had the eternal comparisons with Beethoven behind him, but not much time left, who was on a radically new path.

"Like an angry celestial phenomenon," said Robert Schumann, the E-flat major trio swept away from the musical hustle and bustle of the time. Chamber music of symphonic proportions. Chamber music as a musical world laboratory, as a musical mirror of the world, as chamber music never was even with Beethoven and symphonic music only became so again with Mahler.

At that time, Christian Tetzlaff said later, they were not concerned with correctness, but with technical perfection, with expression. For truthfulness. About inevitability. The trios - neither the circumstances of their creation nor those of their recording - became necessary music.

Because the Tetzlaffs and Lars Vogt, who is a genius when it comes to interpretive humility, don't engage in an emotional or technical battle to outdo each other, because they listen to the secondary voices, which are everything here, they speak, let them become transparent. Instigated by Lars Vogt, the three of them cultivate a culture of musical debate that makes you very quiet, especially given the current tumult in the world.

Not only whoever goes into the studio with Schubert's E flat major trio will have to be judged by it, but everyone who makes chamber music. At the end you are dead sad that the story of Lars Vogt did not go on. And happy as one of those gods who were so sympathetic to him, one is that this recording exists.

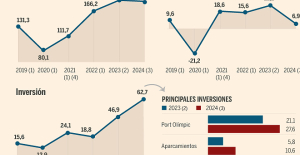

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives

War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte

First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025

Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025 Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 In the United States, a Boeing 767 loses its emergency slide shortly after takeoff

In the United States, a Boeing 767 loses its emergency slide shortly after takeoff The A13 motorway will not reopen on May 1

The A13 motorway will not reopen on May 1 More than 1,500 items for less than 1 euro: the Dutch discounter Action opens a third store in Paris

More than 1,500 items for less than 1 euro: the Dutch discounter Action opens a third store in Paris 100 million euros in loans, water storage, Ecophyto plan… New measures from the executive towards farmers

100 million euros in loans, water storage, Ecophyto plan… New measures from the executive towards farmers New York justice returns 30 works of art looted from Cambodia and Indonesia

New York justice returns 30 works of art looted from Cambodia and Indonesia Les Galons de la BD dedicates War Photographers, a virtuoso album on the Spanish War

Les Galons de la BD dedicates War Photographers, a virtuoso album on the Spanish War Theater: Kevin, or the example of an academic failure

Theater: Kevin, or the example of an academic failure The eye of the INA: Jean Carmet, the thirst for life of a great actor

The eye of the INA: Jean Carmet, the thirst for life of a great actor Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Ligue 1: PSG with Dembélé up front and Navas in goal against Le Havre, Mbappé on the bench

Ligue 1: PSG with Dembélé up front and Navas in goal against Le Havre, Mbappé on the bench Serie A: no goal or winner between Juventus and AC Milan

Serie A: no goal or winner between Juventus and AC Milan Six nations F: in video, the summary of France-England

Six nations F: in video, the summary of France-England Champions League F: Barcelona in the final by beating Chelsea

Champions League F: Barcelona in the final by beating Chelsea