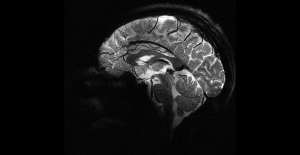

Ancient viruses that infected vertebrates hundreds of millions of years ago played a crucial role in the evolution of our advanced brains and large bodies, a new study suggests.

This work, published Thursday in the journal Cell, examines the origins of myelin, an insulating fatty membrane that forms around nerves and allows electrical impulses to be distributed more quickly.

According to the authors, a genetic sequence acquired from retroviruses – viruses that invade their host's DNA – is crucial for myelin production. And this code is found today in modern mammals, amphibians and fish. “What I find most remarkable is that all this diversity of known modern vertebrates, and the sizes they have reached – elephants, giraffes, anacondas… – would not have happened” without the infection of these retroviruses, neuroscientist Robin Franklin, co-author of the study, told AFP.

Researchers searched genome databases to try to uncover genetic factors associated with myelin production. Tanay Ghosh, a biologist and geneticist working with Mr. Franklin, was particularly interested in the mysterious "non-coding" regions of the genome, which have no apparent function and were at one time considered useless, but which are now recognized as having importance in evolution.

His research resulted in a sequence derived from a retrovirus, which has long been in our genes, and which the researchers named “RetroMyelin”. To verify their discovery, they carried out experiments consisting of deleting this sequence in rats, and observed that they then no longer produced a protein necessary for the formation of myelin.

The scientists then looked for similar sequences in the genomes of other species, and found similar code in jawed vertebrates - mammals, birds, fish, reptiles and amphibians - but not in jawless vertebrates or invertebrates. They concluded that the sequence appeared in the tree of life around the same time as jaws, that is, around 360 million years ago.

The study was called a “fascinating insight” into the history of our jawed ancestors by Brad Zuchero of Stanford University, who was not involved in the work. “There has always been a selection pressure to make nerve fibers conduct electrical impulses more quickly,” emphasized Robin Franklin. “By doing that faster, then you can act faster,” he explained, which is useful for predators chasing prey, or prey trying to flee.

Myelin allows rapid conduction of these signals without increasing the diameter of nerve cells, allowing them to be brought closer together. It also provides structural support, meaning the nerves can grow further, allowing the development of larger limbs. In the absence of myelin, invertebrates have found other ways to transmit electrical signals quickly: giant squid, for example, are equipped with larger nerve cells.

Finally, the team of researchers wanted to understand whether the viral infection had occurred once, in a single ancestral species, or several times. To answer this question, they analyzed RetroMyelin sequences from 22 species of jawed vertebrates. These sequences were more similar within a species than between different species. This suggests that multiple waves of infection occurred, contributing to the diversity of vertebrate species known today, according to the researchers.

“We tend to think of viruses as pathogens, agents causing disease,” noted Robin Franklin. But the reality is more complicated, he says: at different times in history, retroviruses entered the genome and integrated into the reproductive cells of species, allowing them to be passed on to subsequent generations. One of the best-known examples is the placenta - characteristic of most mammals - acquired from a pathogen integrated into the genome a long time ago.

For Tanay Ghosh, this discovery on myelin could only be a first step in an emerging field. “There is still a lot to understand about how these sequences influence different evolutionary processes,” he said.

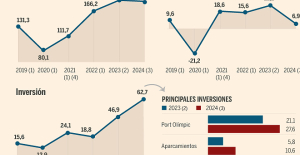

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives

War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” Beware of the three main sources of poisoning in children

Beware of the three main sources of poisoning in children First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte

First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025

Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025 Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs In the United States, a Boeing 767 loses its emergency slide shortly after takeoff

In the United States, a Boeing 767 loses its emergency slide shortly after takeoff The A13 motorway will not reopen on May 1

The A13 motorway will not reopen on May 1 More than 1,500 items for less than 1 euro: the Dutch discounter Action opens a third store in Paris

More than 1,500 items for less than 1 euro: the Dutch discounter Action opens a third store in Paris 100 million euros in loans, water storage, Ecophyto plan… New measures from the executive towards farmers

100 million euros in loans, water storage, Ecophyto plan… New measures from the executive towards farmers New York justice returns 30 works of art looted from Cambodia and Indonesia

New York justice returns 30 works of art looted from Cambodia and Indonesia Les Galons de la BD dedicates War Photographers, a virtuoso album on the Spanish War

Les Galons de la BD dedicates War Photographers, a virtuoso album on the Spanish War Theater: Kevin, or the example of an academic failure

Theater: Kevin, or the example of an academic failure The eye of the INA: Jean Carmet, the thirst for life of a great actor

The eye of the INA: Jean Carmet, the thirst for life of a great actor Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Tennis: “I need to regain confidence in my body,” explains Rafael Nadal

Tennis: “I need to regain confidence in my body,” explains Rafael Nadal NBA: Orlando returns to level with Cleveland in the 1st round of the play-offs

NBA: Orlando returns to level with Cleveland in the 1st round of the play-offs Tennis: Iga Swiatek in the round of 16 at full speed

Tennis: Iga Swiatek in the round of 16 at full speed “It was exceptional here in Chaban-Delmas”: Escudero looks back on the excitement around France-England

“It was exceptional here in Chaban-Delmas”: Escudero looks back on the excitement around France-England