If the perpetrator of a film is known from the start, even confesses to his crime, and the police also know about it, then there are really only two ways to keep the audience in line: Either you sow doubts about the viewers who are trained for turning point to the apparent guilt of the accused. Or one promises to unravel the why: the question of how it came about that X did Y one day.

In view of these contemporary expectations, it is almost a provocation when, after the perpetrator has been initially announced, neither an alternative suspect is put forward nor an ambitious motivational framework is set up that allows the viewer to sink back into his cinema seat and say: “Oh, in one of those If so, I would have done it under those circumstances.”

Winner of the César for Best First Feature and the Grand Jury Prize at Cannes, the French feature film Saint Omer arrives with an implicit and then deliberately broken promise to explain within two hours why a woman out of the blue abandons her 15-month-old daughter on the beach and lets the tide wash her away. The woman does not deny what she did, but she does not consider herself guilty. "That's why I'm here," she says at the beginning of the process and says: To understand why she did it. She doesn't know that herself. She hopes that the experts, the lawyers and the judge will explain it to her. For almost the entire film we see Laurence Coly (greatly chilled: Guslagie Malanda), a Senegalese philosophy doctoral student, in only one shot: standing in the dock, with a stoic expression on her face, looking towards the judge.

Only two scenes deviate from the scheme: at the beginning she carries her child into the sea and at the end she collapses in the lap of her defender. Otherwise, the shots are long, the camera lingers on faces and bodies for small eternities, documenting the mere breathing of the people. Once she's there, pointing at the wood paneling of the courtroom, but it's only when the judge asks Coly to stand that her head peeks into the frame from below.

It is such framing and breaks with frames that make “Saint Omer” aesthetically interesting in places. In terms of content, Alice Diop's directorial work differs from a conventional court drama in that it offers little suspense, but offers remarkable philosophical reflections. Professor Rama (Kayije Kagame), who follows the process from the audience bench, has chosen "Shipwrecked Medea" as the working title for her next book. Her publisher tells her that the title doesn't go down so well because many don't know who Medea is. "Okay," says Rama. And laughs uncertainly: "But everyone knows who Medea is, right?" Where the screenplay deliberately leaves its reference unexplained at this point, it becomes a bit more concrete with the language philosopher Wittgenstein, about whom Coly wanted to write her dissertation. But even there, his most famous quote (“Whatever one cannot speak about, one must be silent about”) only haunts the film as a silent void.

Only when it comes to the chimeras does Coly's defense attorney draft a detailed plea: All women are chimeras, i.e. monsters, because an unborn baby, even if it doesn't survive, gives parts of itself to the mother and vice versa the mother parts of to the baby. It is suggested that all of us - all women and all viewers - are complicit in Coly's act, and in turn capable of a similar act ourselves. But that remains a mere assertion. The sparseness of the staging makes it difficult to sympathize and fear.

Where contemporary series often psychologize the responsibility of a person with various childhood traumas and outdo each other in their crassness, here the cause research fails crashing. Coly tells of a sheltered, privileged childhood. She herself can only explain her act as "witchcraft". No matter how hard her defense attorney tries to portray the accused's relationship with a Frenchman, the child's father, who is thirty years older than her, as fatal, she also characterizes Coly as a migrant who disappears from her environment to the point of madness was brought, and even if an attempt is made to contextualize her act against the background of her foreign culture - Coly's motives are not really tangible to anyone present.

The fact that the film is more documentary-sociological and less suspenseful-dramatic is not surprising given Diop's origins in documentary film. Here, too, she faithfully adheres to the true model: in 2016, the philosophy student Fabienne Kabou was sentenced to twenty years in prison in France for the murder of her daughter. Diop himself sat in the courtroom.

The extrajudicial everyday life of Professor Rama, who acts as Diop's alter ego and, in contrast to Coly, is allowed to leave the courtroom, does not loosen up the static interrogation. Between all the insignificant (spreading a blanket on the hotel bed, going out to eat, watching TV) and cheesy details (stroking her pregnant belly, crying on the phone to her partner), moments of real charm are rare - like when Coly's mother curious and also a bit proud, she buys all the daily newspapers because each one reports about her daughter. The drama largely lacks such fresh, habit-displacing spotlights on the everyday, as well as existential absurdities, such as those told in Camus' "The Stranger" in the light of a similarly unmotivated act.

"Saint Omer" indulges a little too much in its own incoherence, incompleteness and toughness - which can only be justified with the idea that court processes and the human psyche are like that: an act like this cannot be explained, so all attempts must inevitably come to nothing.

In the end, Coly will never have left the rigid frame of the courtroom, the camera or the cinema screen. The film thus shows, sometimes more and sometimes less intentionally, the limitations of the legal, psychoanalytic and artistic means of penetrating into man and his abysses.

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza

Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza Israel prepares to attack Rafah

Israel prepares to attack Rafah First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte

First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025

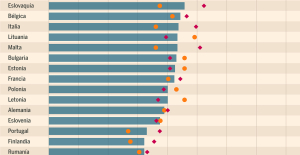

Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025 Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Falling wings of the Moulin Rouge: who will pay for the repairs?

Falling wings of the Moulin Rouge: who will pay for the repairs? “You don’t sell a company like that”: Roland Lescure “annoyed” by the prospect of a sale of Biogaran

“You don’t sell a company like that”: Roland Lescure “annoyed” by the prospect of a sale of Biogaran Insults, threats of suicide, violence... Attacks by France Travail agents will continue to soar in 2023

Insults, threats of suicide, violence... Attacks by France Travail agents will continue to soar in 2023 TotalEnergies boss plans primary listing in New York

TotalEnergies boss plans primary listing in New York La Pléiade arrives... in Pléiade

La Pléiade arrives... in Pléiade In Japan, an animation studio bets on its creators suffering from autism spectrum disorders

In Japan, an animation studio bets on its creators suffering from autism spectrum disorders Terry Gilliam, hero of the Annecy Festival, with Vice-Versa 2 and Garfield

Terry Gilliam, hero of the Annecy Festival, with Vice-Versa 2 and Garfield François Hollande, Stéphane Bern and Amélie Nothomb, heroes of one evening on the beach of the Cannes Film Festival

François Hollande, Stéphane Bern and Amélie Nothomb, heroes of one evening on the beach of the Cannes Film Festival Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Medicine, family of athletes, New Zealand…, discovering Manae Feleu, the captain of the Bleues

Medicine, family of athletes, New Zealand…, discovering Manae Feleu, the captain of the Bleues Football: OM wants to extend Leonardo Balerdi

Football: OM wants to extend Leonardo Balerdi Six Nations F: France-England shatters the attendance record for women’s rugby in France

Six Nations F: France-England shatters the attendance record for women’s rugby in France Judo: eliminated in the 2nd round of the European Championships, Alpha Djalo in full doubt

Judo: eliminated in the 2nd round of the European Championships, Alpha Djalo in full doubt