After years of mass unemployment in the 1990s and early 2000s, an employment miracle has taken place in Germany that was hardly slowed down even by the global financial crisis and the corona pandemic. On the contrary, in 2022, employment subject to social security contributions has climbed to an all-time high.

The unemployment rate dropped to levels that were still considered wishful thinking at the turn of the millennium. No wonder that the question of the costs of structural change, insolvency and job losses faded into the background in this environment. Now the war in Ukraine and the looming recession, but also the ecological transformation that is becoming ever more urgent, have put these questions back on the agenda in Germany as well.

While the focus of the corona pandemic was on companies from the catering or retail trade with comparatively few employees, the current problems surrounding energy prices are fueling the fear that masses of jobs in German industry are on the verge of disappearing.

So what happens to people who lose their jobs in the crisis? Central economic and social questions are why, under what circumstances, to what extent and for what period of time employees have to bear loss of earnings after losing their job.

In order to answer these questions, economic research compares employees who lost their jobs due to a company's insolvency with employees whose employer was able to assert itself in the market. By comparing with a control group, the consequences of acute crises, but also of structural change, can be examined causally.

The focus on the insolvency of companies reduces the risk of also recording those dismissals for which employees are directly responsible, for example through personal misconduct.

Studies from Great Britain and the USA sometimes find huge and long-lasting loss of earnings of up to 30 percent. The findings are somewhat better for Germany: In a recently published study for the period before and during the financial crisis at the end of the 2000s, the labor economists Daniel Fackler, Jens Stegmaier and I show that the decline in annual income from work in the year of the employer's insolvency compared to the control group is about 25 percent.

After five years, the loss drops to 10 percent. Part of the decline is due to a short-term lower likelihood of being employed: some laid-off workers are unable to find a new job quickly. What is important in the long term, however, is a permanent decline in gross wages.

A key finding is that wage losses when small businesses go bankrupt are close to zero. On the other hand, employees from insolvent industrial companies with more than 100 employees have to accept painful and sometimes permanent gross wage losses of 10 to 15 percent.

In order to be able to better understand the reasons and the individual impact of wage losses, a classification into high and low wage employees as well as high and low wage companies is instructive. High-wage workers are people who earn above average, no matter where they work.

High-wage companies pay all of their employees more than their competitors. Based on this classification, a key reason for permanent wage losses becomes apparent: Laid-off workers often have to switch to low-wage companies and only rarely manage to move up to better-paying companies afterwards.

A second new finding, which is also explosive in terms of social policy, is that low-wage employees in particular have to switch to low-wage companies after insolvency. As a result, bankruptcies and company closures are accelerating a trend that began in Germany a few decades ago and has significantly increased wage inequality: the increasing sorting of high-wage employees into high-wage companies and low-wage employees into low-wage companies.

This sorting is caused, for example, by outsourcing: While canteen employees, security guards and other employees with formally low qualifications were still (tariff) employees in high-wage companies in the 1980s, today they often work for low-paying service providers, sometimes even at the same workplace. Nevertheless, there are numerous companies that have not followed this trend. Due to the insolvency of such companies, the missing sorting is now being made up for.

What do these results mean in the light of the coming challenges that rising prices for energy and primary products are confronting German industry with? In 2021, it was mainly smaller companies outside of industry that were affected by corona restrictions and their existence was in some cases endangered, but industrial companies are more likely to be affected at the moment.

A look at the current figures for the IWH insolvency trend already shows a clear shift. In 2021, for example, only 23 percent of the jobs in the largest insolvencies were in industry, in 2022 it was 35 percent. The number of industrial jobs affected by these insolvencies rose by half.

The above study results imply that the average wage losses per laid-off employee in 2021 were rather small. But for a few months now, more and more employees have seen their companies go bankrupt, who will be confronted with severe wage and earnings losses.

So far, so worrying. However, there are good reasons why the situation is not as bleak as it might appear at first glance. First, the rampant labor shortage is now significantly increasing the chances of re-employment for laid-off workers – a circumstance that was not yet so strongly reflected in the study on the financial crisis. Last but not least, we need many qualified employees for the ecological renewal of the German economy.

Secondly, studies show that the German labor market has so far proven to be very robust in the face of other major changes such as the globalization push at the turn of the millennium and the steadily increasing level of automation. On balance, jobs in Germany have not been permanently lost and wage levels have not fallen sharply.

Thirdly, labor market research shows that the financial losses after losing a job measured in terms of net household income, i.e. after taxes and social transfers, are very small in Germany and also significantly lower than in the case of gross wages. A job loss in Germany is financially cushioned comparatively well by the existing transfer and tax system.

The following therefore applies: Even if the current energy price shocks have led to production declines, especially in the energy-intensive sectors of German industry, and jobs in these companies are at risk, the state should allow this structural change. Qualified employees are desperately needed in many places. In this environment, there is no threat of mass unemployment or large-scale loss of income.

professor dr Steffen Müller heads the Structural Change and Productivity department at the Leibniz Institute for Economic Research Halle (IWH).

"Everything on shares" is the daily stock exchange shot from the WELT business editorial team. Every morning from 7 a.m. with our financial journalists. For stock market experts and beginners. Subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Amazon Music and Deezer. Or directly via RSS feed.

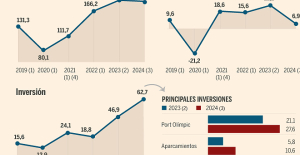

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros

B:SM will break its investment record this year with 62 million euros War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives

War in Ukraine: when kyiv attacks Russia with inflatable balloons loaded with explosives United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte

First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025

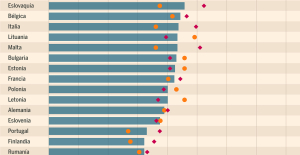

Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025 Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 The A13 motorway will not reopen on May 1

The A13 motorway will not reopen on May 1 More than 1,500 items for less than 1 euro: the Dutch discounter Action opens a third store in Paris

More than 1,500 items for less than 1 euro: the Dutch discounter Action opens a third store in Paris 100 million euros in loans, water storage, Ecophyto plan… New measures from the executive towards farmers

100 million euros in loans, water storage, Ecophyto plan… New measures from the executive towards farmers “He is greatly responsible”: Philippe Martinez accuses Emmanuel Macron of having raised the RN

“He is greatly responsible”: Philippe Martinez accuses Emmanuel Macron of having raised the RN Les Galons de la BD dedicates War Photographers, a virtuoso album on the Spanish War

Les Galons de la BD dedicates War Photographers, a virtuoso album on the Spanish War Theater: Kevin, or the example of an academic failure

Theater: Kevin, or the example of an academic failure The eye of the INA: Jean Carmet, the thirst for life of a great actor

The eye of the INA: Jean Carmet, the thirst for life of a great actor The Nuc plus ultra: St Vincent the Texane and Neil Young the return

The Nuc plus ultra: St Vincent the Texane and Neil Young the return Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Paris 2024 Olympic Games: “It’s up to us to continue to honor what the Games are,” announces Estanguet

Paris 2024 Olympic Games: “It’s up to us to continue to honor what the Games are,” announces Estanguet MotoGP: Marc Marquez takes pole position in Spain

MotoGP: Marc Marquez takes pole position in Spain Ligue 1: Brest wants to play the European Cup at the Stade Francis-Le Blé

Ligue 1: Brest wants to play the European Cup at the Stade Francis-Le Blé Tennis: Tsitsipas released as soon as he entered the competition in Madrid

Tennis: Tsitsipas released as soon as he entered the competition in Madrid