"The monetary part of the indemnity promised by France to the allied powers is fixed at the sum of seven hundred million francs." This read Article IV of the second Paris Peace Treaty of November 22, 1815.

In previous years, Napoleon's troops had ravaged and devastated large parts of Europe. After his defeat, the victors now demanded this compensation.

Thus began the modern history of reparations. They have since been raised after many wars, and for over 100 years Germany has been one of the biggest beneficiaries. But then, after the First World War, the tide turned. Now it was Germany that was to pay off enormous sums.

After the Second World War, most of the victors did without it – for good reason. But with the Polish demands for war reparations of 1.3 trillion euros, the issue of reparations is back on the table.

Of course, there has always been spoils of war. tribute payments as well. However, with the second Paris peace treaty, the compensation payments were precisely quantified for the first time, recorded in a detailed document and distributed to several recipients.

The majority of those 700 million francs went to Germany at the time. Prussia received 100 million, the other German states together another 100 million. In addition, 60 million were to be paid to Prussia and Bavaria so that they could build fortifications on the border with France - the Palatinate belonged to Bavaria at the time and thus bordered on France.

In addition, France had to pay for the occupation costs, war losses of the victors and even for old, defaulted government bonds. This increased the sum to around 1.6 to 1.9 billion francs. Estimates assume that the country's economic output was around 9.2 billion at the time, so the compensation amounted to around 20 percent of that. France paid.

Three generations later, after losing the war against Germany in 1870/71, France had to pay again. This time the newly created German Empire received five billion francs in gold. That corresponded to 1,450 tons of the precious metal and about 25 percent of France's economic output at the time.

In Germany, these reparations led to an economic boom, the money flowed into investments, for example in railway construction, but was also used to repay war bonds.

That was the blueprint for the plans of the German Empire at the beginning of the First World War. "As things stand, the only way forward for the time being is to postpone the final settlement of the war costs by means of credit to the future, to the conclusion of peace and to the time of peace," said Karl Helfferich, State Secretary in the Reich Treasury in a Reichstag speech in August 1915

However, these credits should be triggered again by the vanquished after a victory. “The instigators of this war deserve the weight of the billions; they may drag it through the decades, not us.”

Berlin implemented this in the separate peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which Germany concluded with revolutionary Russia in early 1918. It forced the Soviets to pay six billion rubles in compensation, payable over many years. However, hardly anything flowed from it, because shortly afterwards Germany had to admit defeat to the western powers.

The Versailles Treaty, which ended the war, specifically named Germany as the sole culprit of the war, and this was the legal basis for the Allies to in turn demand reparations from Germany. The London payment plan of May 1921 fixed 132 billion gold marks for this.

The mark of the time before the war is referred to as gold mark, since it was still linked to gold at that time. One mark consisted of exactly 0.358423 grams of gold, so 132 billion gold marks corresponded to 47,000 tons of gold, about 32 times as much as France had to pay in 1871. It was also more than the entire German economic output for a year.

Berlin accepted the demands, but only under threat of military force. Nobody on the German side really wanted to pay this amount. It is disputed whether this was simply not possible. The money could probably have been raised if the propertied strata had been subject to a property tax. However, this was not politically feasible.

Instead, governments churned up national budgets, financed reparations and other expenditures on credit, and thus triggered hyperinflation. In France, there was always the suspicion that Berlin had brought about this on purpose in order to show the world that it was simply not in a position to pay the reparations economically.

It is unlikely that this was really the plan. But as a result, the reparations after the currency reform from 1924 were actually renegotiated and significantly reduced.

The price, however, was the complete disruption of the German economy in the face of inflation, including the impoverishment of broad sections of the population. For them, the phase of democracy in the Weimar Republic was primarily an experience of declassification - a factor that paved the way to the Nazi dictatorship.

After the Second World War, the western powers drew the necessary conclusions from this experience. The Potsdam Agreement of August 2, 1945 stipulated that the occupying powers should, to a certain extent, obtain their own compensation through dismantling and supplies in their respective zones. However, the Western Allies quickly stopped this practice.

Instead, the USA launched the Marshall Plan, which expressly also benefited reconstruction in the Federal Republic. The creation of a prosperous West German state and its integration into the West had pushed aside the idea of compensation.

The Soviet Union, on the other hand, continued dismantling in the eastern zone until 1953. Its value is difficult to quantify, but it was significant. Sometimes there is even talk of the highest compensation sums paid in the 20th century.

A final settlement of possible claims for reparations against Germany should remain reserved for a peace treaty. However, in 1953 and 1970 Poland waived such claims in treaties. In addition, it made no demands in 1990 when a peace treaty was negotiated in the Two Plus Four talks.

Around 32 years later, Poland is now demanding compensation, and Greece is also making corresponding claims again and again. So far, however, these have always been rejected by the federal government. It is also argued that the Two Plus Four Agreement does not contain a clause on reparations.

However, since these should be regulated in a peace treaty according to the Potsdam Agreement, Berlin sees the issue as closed. However, it is obviously not. Discussions about reparations will continue. Even more than 200 years after their appearance.

"Everything on shares" is the daily stock exchange shot from the WELT business editorial team. Every morning from 7 a.m. with our financial journalists. For stock market experts and beginners. Subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Amazon Music and Deezer. Or directly via RSS feed.

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump

United States: divided on the question of presidential immunity, the Supreme Court offers respite to Trump Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury”

Maurizio Molinari: “the Scurati affair, a European injury” Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza

Hamas-Israel war: US begins construction of pier in Gaza Israel prepares to attack Rafah

Israel prepares to attack Rafah First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte

First three cases of “native” cholera confirmed in Mayotte Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025

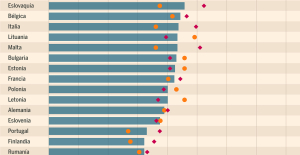

Meningitis: compulsory vaccination for babies will be extended in 2025 Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Falling wings of the Moulin Rouge: who will pay for the repairs?

Falling wings of the Moulin Rouge: who will pay for the repairs? “You don’t sell a company like that”: Roland Lescure “annoyed” by the prospect of a sale of Biogaran

“You don’t sell a company like that”: Roland Lescure “annoyed” by the prospect of a sale of Biogaran Insults, threats of suicide, violence... Attacks by France Travail agents will continue to soar in 2023

Insults, threats of suicide, violence... Attacks by France Travail agents will continue to soar in 2023 TotalEnergies boss plans primary listing in New York

TotalEnergies boss plans primary listing in New York La Pléiade arrives... in Pléiade

La Pléiade arrives... in Pléiade In Japan, an animation studio bets on its creators suffering from autism spectrum disorders

In Japan, an animation studio bets on its creators suffering from autism spectrum disorders Terry Gilliam, hero of the Annecy Festival, with Vice-Versa 2 and Garfield

Terry Gilliam, hero of the Annecy Festival, with Vice-Versa 2 and Garfield François Hollande, Stéphane Bern and Amélie Nothomb, heroes of one evening on the beach of the Cannes Film Festival

François Hollande, Stéphane Bern and Amélie Nothomb, heroes of one evening on the beach of the Cannes Film Festival Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon

Even on a mission for NATO, the Charles-de-Gaulle remains under French control, Lecornu responds to Mélenchon “Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne

“Deadly Europe”, “economic decline”, immigration… What to remember from Emmanuel Macron’s speech at the Sorbonne Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Medicine, family of athletes, New Zealand…, discovering Manae Feleu, the captain of the Bleues

Medicine, family of athletes, New Zealand…, discovering Manae Feleu, the captain of the Bleues Football: OM wants to extend Leonardo Balerdi

Football: OM wants to extend Leonardo Balerdi Six Nations F: France-England shatters the attendance record for women’s rugby in France

Six Nations F: France-England shatters the attendance record for women’s rugby in France Judo: eliminated in the 2nd round of the European Championships, Alpha Djalo in full doubt

Judo: eliminated in the 2nd round of the European Championships, Alpha Djalo in full doubt