The offer sounded tempting: experienced fighters wanted for police action against insurgent barbarians. This was a job very much to the liking of the soldiers who had been unemployed since the end of the Peloponnesian War in Greece (431-404) because they could no longer find their way in civilian occupations. So 401 B.C. Thousands worked as mercenaries in the recruiting offices, especially since the client promised good pay: Cyrus, son of the Persian great king and supreme commander of the satrapies of the world empire in Asia Minor.

What he was up to was not a lucrative campaign against the Pisidians, but a coup of entirely different dimensions. With more than 10,000 Greeks and tens of thousands of other fighters, Cyrus wanted to push his older brother Artaxerxes II off the throne of the Persian Empire. The usurper won the battle but lost his life, leaving his mercenaries in an almost hopeless position. The fact that most of them were nevertheless able to return to their homeland was thanks to a man who had initially only joined their platoon as an observer, but then took over the leadership: Xenophon from Athens (c. 430/25–354).

However, it was not this success that introduced the "Train of the Ten Thousand" into the canon of historical education, but the book that Xenophon wrote about it. His "Anabasis", the "ascent" from the coast of the Aegean over the mountains to the gates of Babylon, has been part of world literature since antiquity. The Romans learned the intricacies of the Attic idiom from her. Even today, students in ancient Greek classes read their first classic with Xenophon. The fact that it is predestined to do so in Latin, like Caesar's "Gallic Wars", has its reason in the fluent, unfussy language and the full story that it tells.

Reason enough for the Bonn ancient historian Wolfgang Will to subject the famous book – one of the most widely read in antiquity – to a lucid revision (“The train of 10,000. The unbelievable story of an ancient mercenary army”. C. H. Beck, see below). Will not only follows the mercenaries and provides the necessary information about the text, but also arranges it in the tricky front positions of the epoch. This includes, for example, that Xenophon wrote his autobiographical account around 380 BC. as a well-to-do landowner on an estate that the Spartans had given him, although he was an Athenian. And that he gave the author's name as Themistogenes of Syracuse, writing in the third person.

Something may explain the origin. The son of a wealthy knight, Xenophon kept his distance from the radical democracy in Athens during the Peloponnesian War against Sparta. After their defeat, he was one of the profiteers of the "Thirty Tyrants" who had used the Spartans as puppets, and served in their cavalry. Despite this, he did not become a foolish supporter of the oligarchy. The philosopher Socrates, to whom he dedicated several writings, saved him from this.

After the fall of the Thirty and the restoration of democracy, Xenophon had good reason to leave his hometown. A friend who had offered himself to Cyrus as an officer offered to introduce him to the Persian court. Xenophon seized the opportunity and moved to Sardis, Cyrus' residence. As a reporter, we would say "embedded journalist", he wanted to join the bandwagon.

With his servants and a pack carried by several horses, Xenophon differed markedly from the mercenaries who had assembled from all over the Greek world. They were mostly hoplites, heavily armed foot soldiers who knew how to fight in a disciplined phalanx and were considered the best warriors of their time. But it wasn't citizen soldiers fighting for their city. Their motive was money – on the one hand because they had to earn their living from it in the camp, on the other hand because they wanted to use it later to shape their lives at home. They were followed by a procession of perhaps ten thousand traders, women and slaves.

At the latest when the train had crossed the Tauros mountains, it dawned on the Greeks that it was not against the Pisidians, but against the great king. By pointing out his brother's full treasure chests, Cyrus was able to avert the mutiny. A battle broke out at Kunaxa north of Babylon: the Greeks won, but their client fell. The Persian satrap Tissaphernes, a rival of Cyrus, then managed to lure the leaders of the mercenaries to his camp, where they were killed.

That was the moment for Xenophon's appearance. In one of the numerous speeches that run through the book and in which he explains the diplomatic and strategic decisions, the eloquent Athenian put himself up for election as the new commander: "Therefore the new leaders have to be much more circumspect than the earlier ones, the subordinates even now much more discipline and obedience to superiors than before.” The General Assembly accepted.

Since the way back was blocked by the enemy, the army under the joint leadership of Xenophon and a Spartan made their way to the Katabasis, the "descent" to the Black Sea. They passed through regions the Greeks scarcely knew the name of. And since they did not limit themselves to buying food, but harassed the local residents with raids, they saw themselves exposed to a permanent small war.

This made the "Anabasis" a great description of the country. "Fortresses to be conquered, mountains to be climbed, rivers to be crossed, raids to be thwarted," Will writes. Detailed, accurate, and dry, Xenophon reports on the production of beer, the equipment of a Persian armored rider, the subterranean dwellings of the inhabitants and the toxic effects of honey obtained from a species of azalea.

The author describes the massacres, to which the undisciplined mercenaries were tempted by hunger and desperation, without emotion - for example when women first threw their children and then themselves into the depths in order not to be enslaved. "The only pathos," according to Will, "is, as in the 'Odyssey', the longing of those returning home."

The decisive moment at Trebizond (Trabzon) has also gone down in history rhetorically. Xenophon was at the rear guard "as the calling grew more powerful". He mounted his horse, "and soon they hear the soldiers shouting 'thálatta, thálatta' (the sea, the sea) and the word being passed from man to man. So everyone ran, including the rearguard... and when everyone had reached the top, they hugged each other with tears."

"The sea, the sea" has since become a symbol of salvation from impossible situations. In "Sea Greeting" Heinrich Heine created a poetic monument to the reputation of neo-humanism: "Thalatta! Thalatta! / Hail, eternal sea! / Greetings ten thousand times, / From a joyful heart, / As once greeted you / Ten thousand Greek hearts.”

With that, the "kata basis" was done in 122 days and almost 1500 kilometers, but only half of the way back. But now the 8,000 or so that were left were scattered. Everyone tried to get home by ship. Xenophon reached Byzantium with part of the army, later Constantinople and today's Istanbul, experienced wild adventures in Thrace and was finally able to hand over his people to a Spartan general in Pergamon.

But the hope of returning home was dashed. Because Cyrus had supported the Spartans in the Peloponnesian War, Xenophon had been exiled from the restored democracy in Athens. Therefore he now joined the Spartan king Agesilaus, who defended the hegemonic position of his city with some success. As thanks, he was given an estate not far from Olympia, where he devoted himself to family life and writing. However, this was not an end in itself.

Will makes it clear how many apologetic undertones there are in "Anabasis". On the one hand, there was the accusation of infidelity that numerous mercenaries – many of whom were still alive – had spread. On the other hand, a certain Sophainetos had published an "Anabasis Kyrou" in which Xenophon probably did not find himself sufficiently appreciated. The charge in Athens of collaborating with the enemy was probably even heavier. The triple motive of the defense would explain why Xenophon wrote in the third person and hid behind a pseudonym.

Maybe he was successful. Athens allowed him to return after losing his estate after Sparta's defeat by Thebes in the 360s. Xenophon is said to have died in Corinth while his sons were fighting for the old hometown.

His authorship of the "Anabasis" was soon exposed and was to serve as a manual for another "Ascension". Like many military men, Alexander the Great read the work when he died in 334 BC. to conquer the Persian Empire. It is not for nothing that the Roman Senator Arrian, who wrote the most important source on Alexander's campaign in the 2nd century AD, gave it the name "Anabasis".

He adopted the division into seven books and lamented: "So it comes about that Alexander's deeds are far less known than the miserable quisquilia of an earlier time. Yes, it is even that procession of ten thousand with Cyrus ... just like their return march under Xenophon, precisely because of this Xenophon, it is far better known to the people than an Alexander with all his achievements.” A greater compliment for Xenophon can hardly be imagined.

Wolfgang Will: “The Train of 10,000. The incredible story of an ancient mercenary army". (C. H. Beck, Munich. 314 p., 28 euros)

You can also find "World History" on Facebook. We are happy about a like.

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

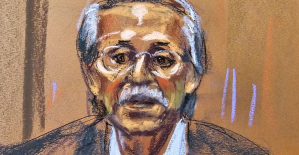

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

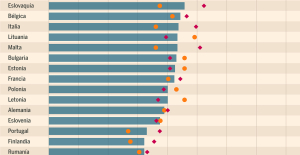

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation

Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application

Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application “I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing

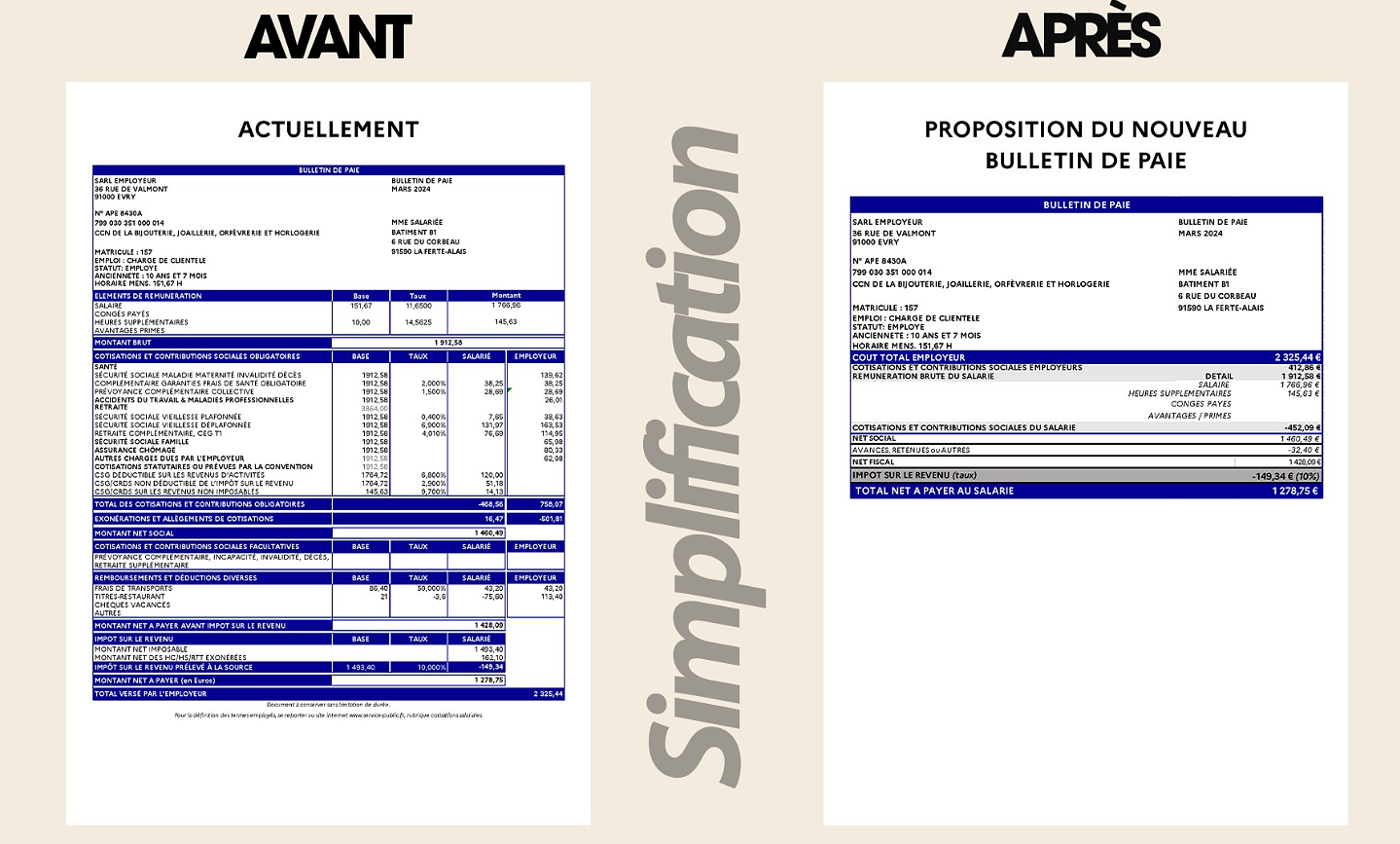

“I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy 25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits

25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan

At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga

Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker

Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops

OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet

Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid

Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid