If a hiker were allowed to carve out the ideal travel destination, then Georgia would come out: the mighty mountain range of the Greater Caucasus with its 5000 meter high peaks for high alpine tours, the green low mountain range of the Lesser Caucasus with its forests and the old Borjomi spa for leisurely hiking for families. In addition, legendary peaks like the Kasbek, to which the Greek gods chained Prometheus because he had stolen their fire. And: rarely masses of day-trippers like in the Alps.

The most famous long-distance hiking trail leads in four days from Mestia to Uschguli, right through the wild Svaneti. The inhabitants of the high valleys on the border with Russia have been feared as warriors since ancient times, and centuries-old defense towers watch over their stone houses - even in the tourist center of Mestia with its futuristic airport, where every second house is a restaurant or guesthouse.

Passing the 4700 meter high horns of the Ushba you hike eastwards, through mountain forest, over grassy slopes, past rhododendron bushes, cross an icy river on horseback (where locals wait with horses) and at the end stand stunned in front of Uschguli - a village like a medieval backdrop , towered over by the 5200 meter high ice and rock face of Mount Shkhara. Accommodation is in farmhouses, and the families serve dinner in the living room.

If you like it even more lonely, you can extend the tour by four more stages from Chuberi to Mestia - and thus go the first completed section of the Transcaucasian Trail, which should eventually meander through the entire Caucasus. Until then, however, the Georgians still have a lot of undergrowth to clear away from overgrown paths, build serpentines and bridges.

The mountains of the Tusheti region in the east are at least as wild. They can be reached via a single road, the almost 3000 meter high Abano Pass. The Tuschen also planted defense towers on their wide grassy slopes, over which eagles and griffon vultures circle. In half-ruined villages, ram's skulls lie on stone slab shrines where men sacrifice, drink and pray on holidays. If you want to experience the pastoral traditions up close, you have to come in autumn - and cross the Abano Pass with thousands of sheep.

Admittedly, no one flies to Georgia just for swimming. The coast is short, and its fairer half lies unreachable in the breakaway province of Abkhazia. But the Georgians love the dark pebble beaches of their subtropical Riviera. The port city of Batumi is particularly booming. Families and couples walk under palm trees on the beach promenade, bicycles and e-scooters roll in the bike lane.

A bizarre skyline of glass towers and kitsch palaces looms behind. A huge disco ball crowns the double helix with the 33 letters of the Georgian alphabet, and a Ferris wheel turns next to it. For Europeans, the garish mix of styles may seem disconcerting. But Iranians and Russians, Turks and Armenians like to travel to eat fish in seaside restaurants, go out and gamble in the casinos.

Behind the bling, however, lies an ancient history that stretches back to the founding of the city as a Greek colony in ancient times. A little of this can still be seen in the small old town with cobblestone streets and renovated villas from the 19th century. And in Europa Square, where Medea (albeit as a modern statue) stoically stretches the Golden Fleece into the sky amidst the hustle and bustle.

Batumi is especially beautiful to look at from afar: from the Green Cape, where the beach ends at the cliffs. Vacationers snooze on four-poster beds made of bamboo and straw, while young people jump off the pier into the sea at sunset, with a view of the glowing skyline.

The wonderful botanical garden spreads out in the hills behind. Opened in 1912, it served as a substitute for world travel for Soviet citizens. When the humidity is oppressive, you can walk in the shade of Californian giant sequoia, Australian eucalyptus and Chilean araucaria. A fresh breeze blows from the sea. And from the viewing terraces, the view goes over the green, overgrown cliffs.

Wine countries like to boast about their history. But compared to Georgia, they are all upstarts. Vines have been cultivated at the foot of the Caucasus for at least 8000 years, longer than anywhere else in the world.

However, for a long time the past was more glamorous than the present: In the 1980s, Georgia had to deliver cheap wine for the workers in the Soviet Union, the area under vines was almost twice as large as today. The fact that the market for the lovely Plörre collapsed in the 90s was "a stroke of luck", writes Jens Priewe in his standard work "Wein. The Big School”: “Georgia was forced to go back to its traditions.”

These fit perfectly with the organic zeitgeist today - especially the fermentation in huge clay amphorae that are buried in the ground. The mash ferments in these qvevris for weeks, after which the wine is sealed airtight and allowed to mature for six months or longer. Bottled unfiltered, the amber-colored and surprisingly tannic white wines are now the holy grail of every natural wine connoisseur in Kreuzberg or Brooklyn. Priewe therefore praises Georgia as a "key country for modern oenology", the "New York Times" declares it a trendsetter in the world of wine - and recommends the Kakheti region in the east of the country as one of the 52 places to go for 2023.

In the green hills around the regional capital Telavi, travelers will find most of the winegrowers who develop their wines in Qvevri. For ten years, the ancient method has been part of the intangible world cultural heritage of Unesco, the pride of Georgians. However, more than 90 percent of the wines are produced conventionally in steel tanks, especially the white Rkatsiteli or the red Saperavi.

You can taste Qvevri wines at the Vazisubani winery, a mansion from 1891 that is both a restaurant and a hotel (vazisubaniestate.ge). Or at Weingut Schuchmann, whose wine spa also offers grape seed peelings or hot wine baths (schuchmann-wines.com).

The finest base camp for tastings is the town of Sighnaghi, with its hilltop fortress, narrow streets and centuries-old houses with carved balconies. The best time for visitors to check in is mid-September, when the grape harvest begins – and with it, wine festivals across Kakheti.

Any trip to Georgia should start in Tbilisi. Boris Pasternak, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, called the capital, which is home to 1.1 million people today, almost a third of all Georgians, “a mythical creature with a western head and an eastern body”. Long before him, Marco Polo was enchanted by the rich trading city on the Silk Road.

And today, digital nomads swarm with hip restaurants and techno clubs like the world-famous Bassiani, where the young and misfits dance in what used to be a swimming pool beneath the National Stadium.

In order to get an overview of the wonderful chaos of Tbilisi, guests are best off climbing the sacred local mountain Mtatsminda – or taking the cable car straight up to the excursion restaurant. From the terrace, the view sweeps over orthodox churches and mosques, prefabricated buildings and wooden houses with carved balconies, ancient fortress walls and hypermodern glass buildings. And over to the monumental statue of Kartlis Deda (Mother of Georgia). In her right hand she holds a sword, in her left a wine bowl - the fitting reception for friend and foe.

The city was conquered, destroyed and rebuilt 40 times by Arabs and Mongols, Persians, Ottomans and Russians. The oriental heritage is clearly evident in the bathing district of Abanotubani. The mosaic front of the Chreli-Abano Baths shines in a vine-laced blue like the mosques of Isfahan in Iran, the carved balconies of the restaurants rise above the brick domes of the underground thermal baths. If you book a massage in bathroom number five, you will be lathered and massaged like in a hammam.

Softened by thermal water, you stagger through the Art Nouveau district of Sololaki, between city palaces with richly decorated facades. And continue strolling under the 100-year-old plane trees of Rustaveli Boulevard, past the Moorish-style opera house and the neo-baroque theatre, the Parliament and the National Museum. It is definitely worth a visit there, just for the treasury.

Or you can walk down to the Kura River (also called Mtkvari), to the Peace Bridge with its curved, turquoise-colored glass roof, built by star architect Michele De Lucchi. In the park behind are the two tubes of the concert hall, also made of glass. And the Presidential Palace is enthroned on the steep bank above, with a glass dome of course – because ex-President Mikheil Saakashvili liked the Reichstag in Berlin so much.

Nobody comes back from a holiday in Georgia without a few extra kilos. The Danish star chef René Redzepi praises the country's cuisine as "one of the last great undiscovered food cultures in Europe". He is right. Of course, “undiscovered” only applies to ignorant Westerners. In the Soviet Union, the cuisine of southern Arcadia was legendary, and state guests in Moscow were often served Georgian dishes.

The country owes its culinary wealth to centuries of multiculturalism. Armenians, Greeks and Persians lived in the big cities, traders on the Silk Road and the many invaders brought their recipes with them. Writer and orientalist Navid Kermani writes that no other cuisine is so close to Iranian cuisine.

Of course, the mild climate also helps. The first bite into a Georgian tomato feels like an epiphany. At a market, one is amazed at how many variations of walnuts there are. And then all the herbs, the spices!

The sophistication of Georgian cuisine can be seen, for example, in an appetizer that is on the menu in almost every restaurant: badridjani. Fried aubergine strips are spread with walnut paste, rolled and sprinkled with pomegranate seeds. The highlight are the spices in the paste: fenugreek, dried marigold blossoms, onion, garlic, chili - and of course the ubiquitous coriander.

Equally indispensable is tarragon. The cabbage refines the lamb stew Chakapuli in bunches, and there is even tarragon lemonade. And the love of garlic is taken to the extreme with the chicken dish Shkmeruli: A whole chicken is fried in plenty of butter and then cooked in a sauce made of milk and lots of garlic (ten cloves or more). As a side dish and also in between you eat khachapuri, a yeast and white bread with cheese, sour cream and milk. Depending on the region, it is round or oval, in Adjara an egg is beaten over it.

One could go on raving endlessly – about stuffed vine leaves, the Lobio bean stew, the ratatouille variant Adschapsandali. A favorite of many travelers are khinkali: dumplings stuffed with minced meat, seasoned with savory and cumin. Khinkali are considered perfect when the dough has 18 folds. They are eaten with the hand. First you bite off a small corner and slurp the meat broth, then the rest is consumed. To digest, there is a Tschatscha, the traditional marc brandy. Cheers – cheers!

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation

Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application

Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application “I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing

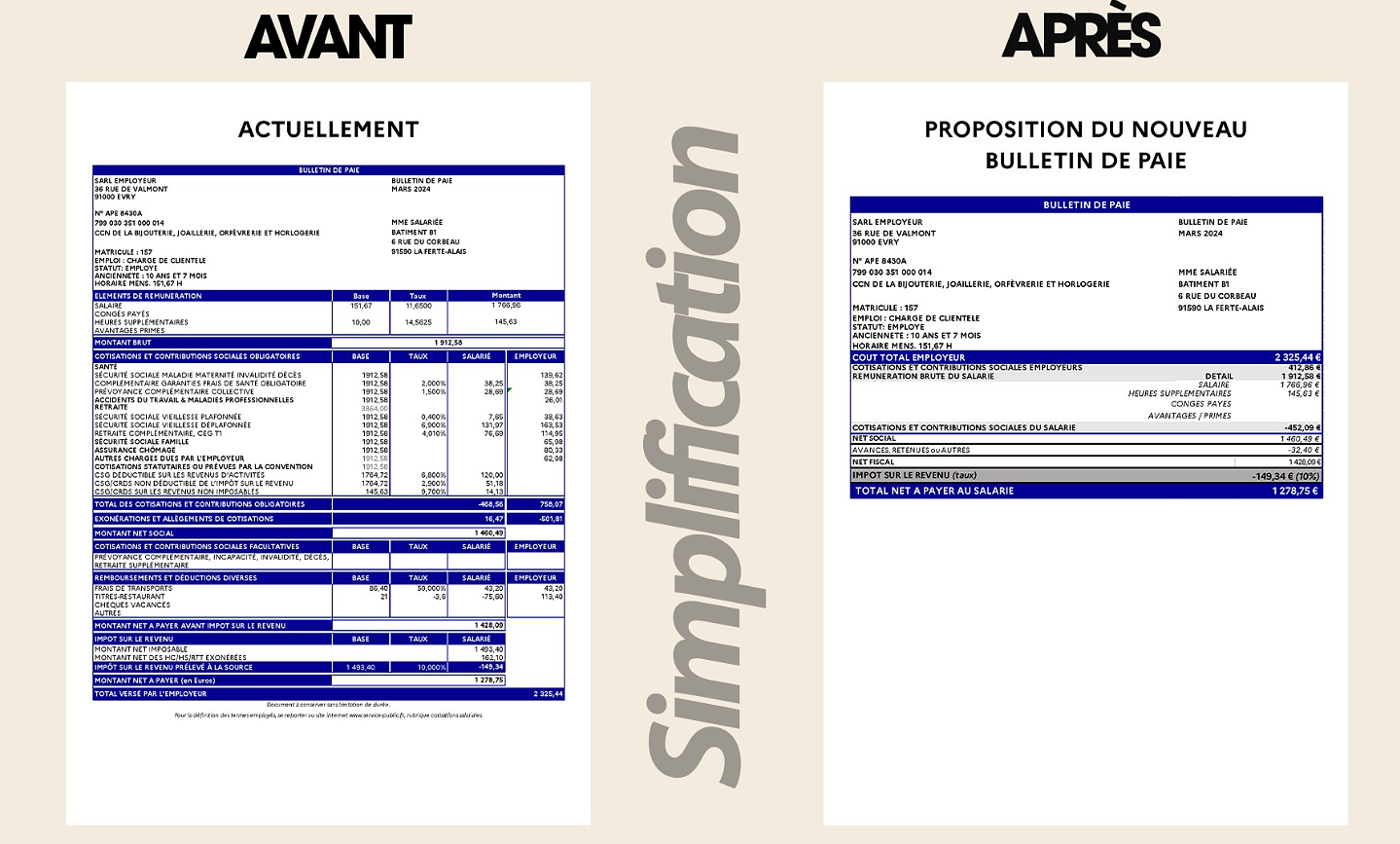

“I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy 25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits

25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan

At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga

Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker

Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops

OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet

Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid

Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid