His great-grandfather, a musician at the court of the Afghan Emperor 150 years ago. His father was a well-known singer and maestro. Bakhsh carried on the family tradition, performing and managing an instrument repair shop.

Until now. The 70-year old had to stop playing music and make his shop a convenience store selling soda.

Six months ago, the Taliban's invasion of Afghanistan has left Kabul without a music scene. The instruments that used to fill the streets of Kucha-e-Kharabat are gone. They were packed by their owners and moved on, putting at risk a centuries-old musical heritage from Afghanistan.

Many have been forced to leave because work is scarce due to the country's economic crisis and fear of the Taliban. Although the Taliban government has not officially banned music, musicians claim that individual Taliban fighters have taken matters into their hands and targeted them, stopping performances and breaking instruments, because they believe music is "haram," which is prohibited by Islamic law.

Nazir Amir Mohammed wept as he said goodbye to his family on a recent afternoon. He was met by a minibus that was waiting to transport him and the other musicians to Iran. There they will be able to practice and share their knowledge with the next generation.

His rubab, a traditional instrument similar to a lute, was hidden in a bag between layers of clothing. It took Mohammed 10 years mastering it.

He said that the Taliban had come to this street and told them music was not permitted. His income was derived from performing at weddings, concerts, and parties, as did most street residents. That is all gone.

People who remain have adjusted to new realities. The street's instrument repair shops have been transformed into small stalls selling chips and soda, or clothing. Many traditional instruments, including harmoniums, lutes, drums, and harmoniums, are kept in hidden places or even buried.

In Kucha Shor's bazaar, which means "Noise Street", instruments are also gone. Shopkeepers now sell kites as a national pastime. The famed music school in Afghanistan, Afghanistan's only one, is now empty. Its pupils and teachers have been evacuated. Outside, the Taliban guard.

Kucha-e-Kharabat's classical music traditions are passed down through the generations. They date back to the 1860s, when Sher Ali Khan, an Afghan emperor, invited Indian masters into Kabul to enrapture Kabul’s royal court.

Afghanistan's unique music fusion is the result of the convergence of two cultures. Afghan folk songs are mixed with Indian classical music. Afghan music, like Indian music, is an oral tradition. The youth learn for years from a single master called an ustad and then carry on their tradition.

Bakhsh's great grandfather, Ustad Khudabakh was one of the first Indian masters who responded to the emperor. Bakhsh, who spent his entire life in music, now sells sodas to make a living. He makes about 100 afghanis ($1) per day. Bakhsh's main customers are worshippers at the mosque nearby.

The shop's former life is now a shell of a harmonium filled with rags. He said, "I don’t know where the guy who asked me to fix it went. He must have gone."

He said, "We don’t have any other skills. Music is our life." "We don’t know how merchants work, and we don’t even know how weapons are used to rob people."

Fearful residents are afraid of Taliban fighters.

Zabiullah Nuri (45), was carrying his harmonium from his shop one month ago when a Taliban patrol spotted him.

"They beat me, and took my instrument. He said that they had broken it with their guns, and sat in his house holding the remnants of his harmonium.

Nuri sold his TV to make ends meet.

He said, "Everything is done, my entire life has changed."

Issa Khan (38), was about an hour into his engagement party at a private residence when a group Taliban stormed in. He was also told that music was prohibited by the militants.

After that, he stopped playing.

Mobin Wesal's home still plays folk songs. The 35-year old singer brings life to the salon, which is empty except for the instruments he has hidden in the corner.

Pashtu's favorite Pashtu song is "Teacher please don’t fail me in the exams." I am an idiot because of love."

He said that he was part of a new generation Afghan musicians who breathed life back into their culture by adding new lyrics and creative styles to the art form.

His younger son sat attentively, listening intently. Wesal motioned toward the boy, "I won’t teach him." He would be in danger.

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated)

What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated) Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation

Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application

Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application “I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing

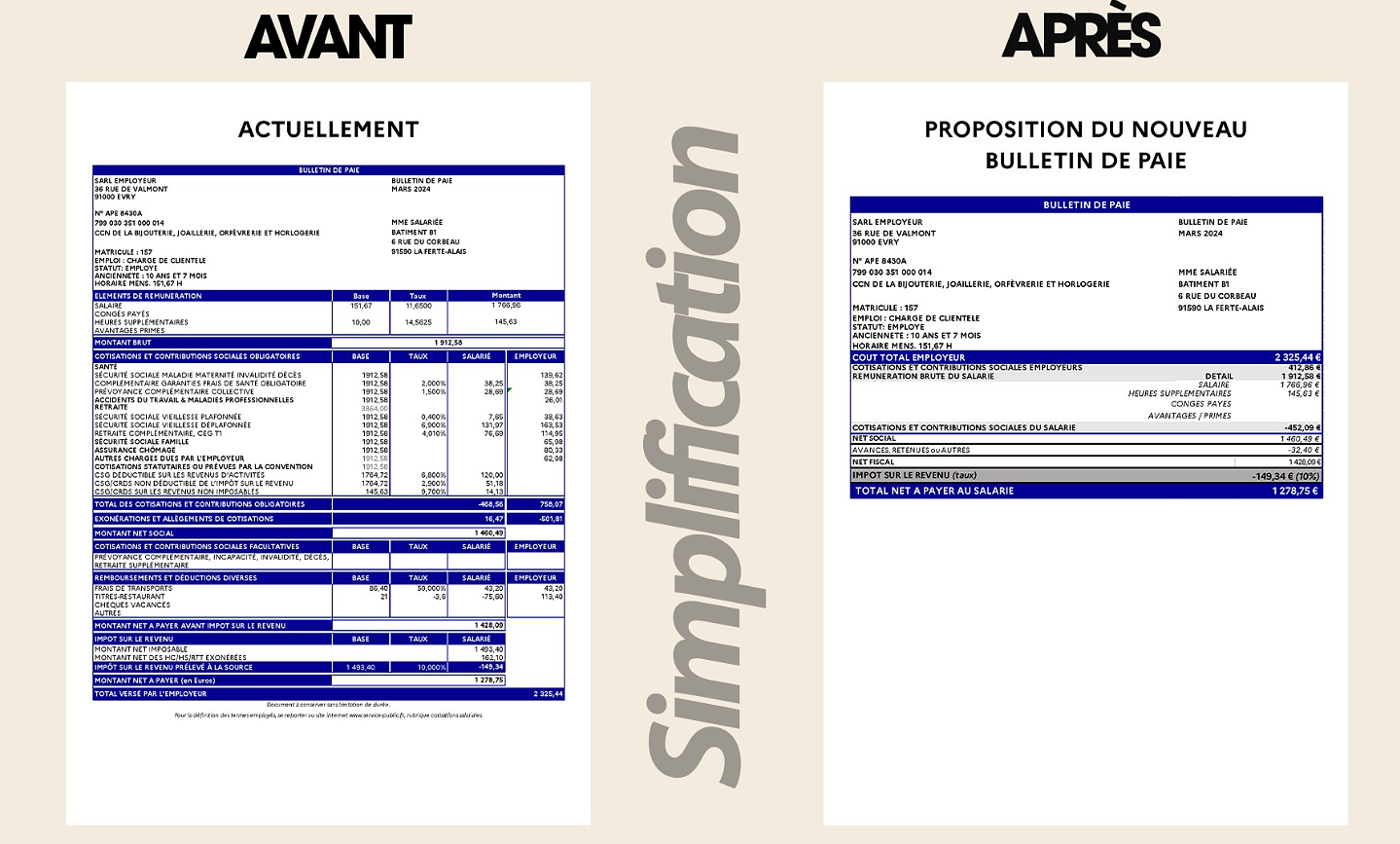

“I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy 25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits

25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan

At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga

Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker

Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops

OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet

Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid

Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid