Maurice Crul appears in a good mood in the foyer of the Vrijen Universiteit Amsterdam and asks in a soft voice to come to his office. From there, the Dutch sociologist dedicates himself to a topic with explosive power: Crul researches "super diverse" cities in which the former majority is only a minority of many. For Crul, the issue isn't whether to accept this scenario, but how to deal with it. Because in many places it is already a reality, elsewhere it is the future.

WORLD: Are we talking past each other as a society when we are already talking about super-diverse cities, while others are still saying: We don't want such cities at all?

Maurice Crul: It's interesting to look at the United States because demographically they're a few decades ahead of us here in Europe. In the big cities, people are used to diversity and are discussing how to deal with it. Nationwide, on the other hand, the political debate tends to ask: Okay, our society is changing – do we even accept that? Those who don't accept this want to go back in time and stop migration altogether. This divided debate can currently be observed in many places, especially in smaller cities, including in Europe. There it says: "We don't want to become like Berlin or Hamburg!"

WORLD: In your research, you try to find out how the concept of super-diversity works by surveying people without a migration background. In short: does it work?

Crul: We have examples across North West Europe where this is already a reality. People without a migration background will also be a minority in German cities. So we said to ourselves: We'll look at it empirically in districts where this reality has arrived. We found that most people see neighborhoods like this as an asset. However, and this is the other side, we see little social interaction between people with and without a migration background in these places. The near and extended social circles of non-migrant people in these very diverse areas are usually quite homogenous.

WORLD: That's strange, isn't it?

Crul: Yes, mostly because the people we spoke to are aware of it themselves. This causes a certain uneasiness, especially for the more progressive people. If you go to their birthday parties, you'll see that their circle of friends isn't particularly diverse. That's because they weren't taught to deal with diversity from an early age.

WORLD: Probably because they didn't have to.

Crul: Because they didn't have to, yes. On the other hand, if you look at those who learned this at a young age, you see very mixed circles of friends. These people also feel more connected to their neighborhood. They interact more often with neighbors who have an immigrant background. It is enriching to learn these skills - social life is better. You feel safer in your neighborhood. So it's important to learn that.

WORLD: How do you do that?

Crul: Apparently it has to be organized for people who didn't learn it early. We have found that the best way is to organize activities that help organize contact for them as a sideline. If you send your child to a mixed school, you will meet parents with a migration background. Both parties are in the role of parents, the children play, one starts to talk. It doesn't feel weird because you have a reason to talk - it's a natural situation. Mixed sports clubs have the same effect. Such things can prevent conflicts that might otherwise have escalated.

WORLD: Can you talk about this topic without playing into the hands of populist narratives? Or do we have to say: Despite all the justified criticism of people like Thilo Sarrazin, they were right in their demographic forecasts?

Crul: I would approach this question differently. There's this illusion, especially among progressives, that we need to celebrate diversity. It's always about a kind of "happy diversity", this naive idea that everything runs by itself. And that is then the answer to anti-migration rhetoric. But what we found is that a diverse society requires effort. It doesn't work by itself. We have to organize this from the bottom up. That, I think, is really the answer to anti-immigration rhetoric.

WORLD: Do you think that will work across the board? That requires coordinated responsibility. Colleagues of yours like Andreas Reckwitz like to diagnose a fragmentation and individualization in modern society, in which people are more likely to detach themselves from such networks.

Crul: Bottom-up initiatives are everywhere and you have to help people get them started. For example parent initiatives in schools: they must not be taken over from above, but the schools and the cities must ask themselves: what do the parents need, how can we help them to act themselves?

WORLD: So you are optimistic?

Crul: I'm generally optimistic, and our data suggests that optimism. A significant number of those with negative attitudes towards diversity, for example, described their personal relationships with people with a migration background as good. They interact as neighbors, in shops, or at work. Their opinions do not always shape their everyday lives.

WORLD: Because then it's about specific people and no longer about abstract masses?

Crul: That's certainly an aspect, but people just don't want to live in a kind of war state all the time. Those who do are not happy in their neighborhoods. They say they feel like strangers there. You feel insecure. Parties critical of migration would then say: You live in a threatening environment and we want to change that. But their only solution is to say: We turn this development around.

WORLD: Which will not work.

Crul: Which won't work! Even the voters of these parties know this, which is why they often behave differently in their everyday lives than the discourse would suggest.

WORLD: How do you reach the people who behave in exactly the same way as the discourse suggests?

Crul: I had this discussion with politicians here in Amsterdam. You can't just propose a meeting in a block like this as a measure and say: We're talking about diversity now. With some certainty these people will not go there. But if you now say: “We are planning a vegetable patch together and want to discuss together how we can manage it.” Then people come together because they want to do something pragmatic. Something like that is happening a lot in Amsterdam right now.

WORLD: In the hope of laying a foundation on which you can eventually celebrate diversity?

Crul: Exactly, then it's about something in common. And then the dynamic is very different because it is based on something concrete and not on any form of ideological intention.

WORLD: So that has to happen at a very local level.

Crul: Yes, locally or even at the individual residence level. And, importantly: from the bottom up.

WORLD: But that doesn't work in more rural areas, where hardly any migrants live?

Crul: I assume – I haven't done any research on this yet – that the principle also applies there. Even in smaller towns, people with a migration background now live. When people talk to each other, it sometimes contrasts their political views. When everyday life drowns out the discourse.

WORLD: However, that does not help if integration has already failed. When people have brought patriarchal structures with them and reject the rules of their new home. How do I handle this?

Crul: Before we started our project on people without a migration background, we looked at people with a migration background. In both studies we were able to identify groups that avoid interethnic contact and consider their own way of life to be superior. In this sense, these groups are even similar. In the case of migrants, we usually associate this attitude with their migration history – but the similarities with those without a migration background show that this has little to do with it. This is a more general phenomenon - subgroups that seem unable to adapt to a changing environment. In either case, this creates an interesting paradox: if you're so convinced of the superiority of your way of life, why worry so much about the impact of other concepts on you or your children? In both cases, this lack of openness makes life more difficult in today's diverse societies and brings with it economic and social disadvantages. This applies to people with and without a migration background.

WORLD: The previous concept of integration - with a clear majority society - always includes a certain degree of adaptation of the minority. However, the initial situation changes; how much does the former majority society have to integrate itself into the construct of the most diverse minorities?

Crul: If you look at the situation in the 70s and 80s, the concept of integration or assimilation made perfect sense at the time. As recently as the 1990s, the child of Turkish immigrants in the Netherlands was one of maybe five or six immigrant children in his classroom. Today, 20 nationalities are represented in a single school class. This means that children without a migration background must also be able to deal with this diversity. We have to think about how we give the children the skills to do this. Although here in Amsterdam you can still send your child to fairly segregated schools. But after that it comes here at my university, where half of the students have a migration background.

WORLD: That's a shock.

Crul: That's a shock! You then prepared your child for a society that no longer exists. At work, too, your child will later work in a very diverse team. If it cannot, it will fail.

WORLD: In Germany, one occasionally hears of cases in which German children in schools are said to have been approached by migrant classmates because of their origin. Have you found evidence of such cases?

Crul: You can see that groups with negative attitudes towards diversity, which may also be self-isolating or segregating, often report this. They feel discriminated against by people with a migration background. There are also a lot of quotes from qualitative surveys. But this effect is clearly related to this group, which is an interesting finding: those who articulate attitudes critical of migration find evidence that they themselves are being discriminated against.

WORLD: If you were to explain it to the people concerned, the reaction would probably be: So now it's our own fault.

Crul: Even for this small group, there are always small opportunities in everyday life to come into contact with migrants. The same applies here: It is important to practice this. You will not convince these people by demanding that they simply welcome diversity.

WORLD: The New Year's Eve riots in big cities like Berlin were a big topic in Germany recently. One of the topics discussed was whether migration is contributing to this or not. What's your assessment?

Crul: I don't know the details of the situation in Germany, so I won't comment on that. But I can draw an interesting parallel with the Netherlands. During Corona there was a lot of unrest among young people here, you probably saw it on the news - there were street fights with the police, public property was destroyed. And these young people came mainly from small to medium-sized towns. Dutch young people without a migration background. Interestingly, no one looked for psychological or sociological explanations. If they had been young migrants, I am sure that people would have asked immediately how these children were brought up.

WORLD: Is there evidence that super-diverse cities are more dangerous than others? Or is that a myth?

Crul: That's a whole separate debate. There is generally more crime in big cities. We also had this debate in the Netherlands. It said: There is more crime in big cities, these cities are also more diverse, so diversity is the reason for the crime rates. It is of course much more complicated. You have to factor in the size of the city, the anonymity; in addition, there are often fewer young people in smaller towns, who tend to get into trouble with the law more often. This debate is very difficult.

WORLD: Today we talked about super-diverse big cities. How long does it take before we start talking about super-diverse villages or entire super-diverse countries?

Crul: You can look again at the United States, where this debate was held decades ago. Everyone knows the obvious examples of super-diverse cities: Los Angeles, New York, Chicago. Nobody thought of Texas. They didn't look to New York to learn how they did it. Now Houston is suddenly changing too, and now they're looking at New York after all. Because it's so quick. In Europe, too, the smaller cities are now looking at the big ones. Because they too are changing – for different reasons, but always in the same direction: more colourful. And fast.

WORLD: That's also what scares people.

Crul: The pace of change is fast, yes. But people also change quickly.

WORLD: What is your advice to cities in Germany that are still at an early stage of this development? How do I handle this?

Crul: I think you have to say - and that requires courage from politicians and decision-makers: Okay, for decades we had an integration policy that focused on migrants and their descendants. But in all these years we have forgotten one group, and that is those without a migration background. So the new direction is not an integration policy, but one that organizes the peaceful coexistence of very different people. This breaks with the tradition that people without a migration background don't have to do anything because they are the hosts.

WORLD: Many people will not like to hear that.

Crul: But it's also something positive. The message to these people must be that your active role also means that you can help shape the future. Previously, you always belonged to a group that was passive - and therefore could not influence the result.

"Kick-off Politics" is WELT's daily news podcast. The most important topic analyzed by WELT editors and the dates of the day. Subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, among others, or directly via RSS feed.

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated)

What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated) Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation

Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application

Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application “I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing

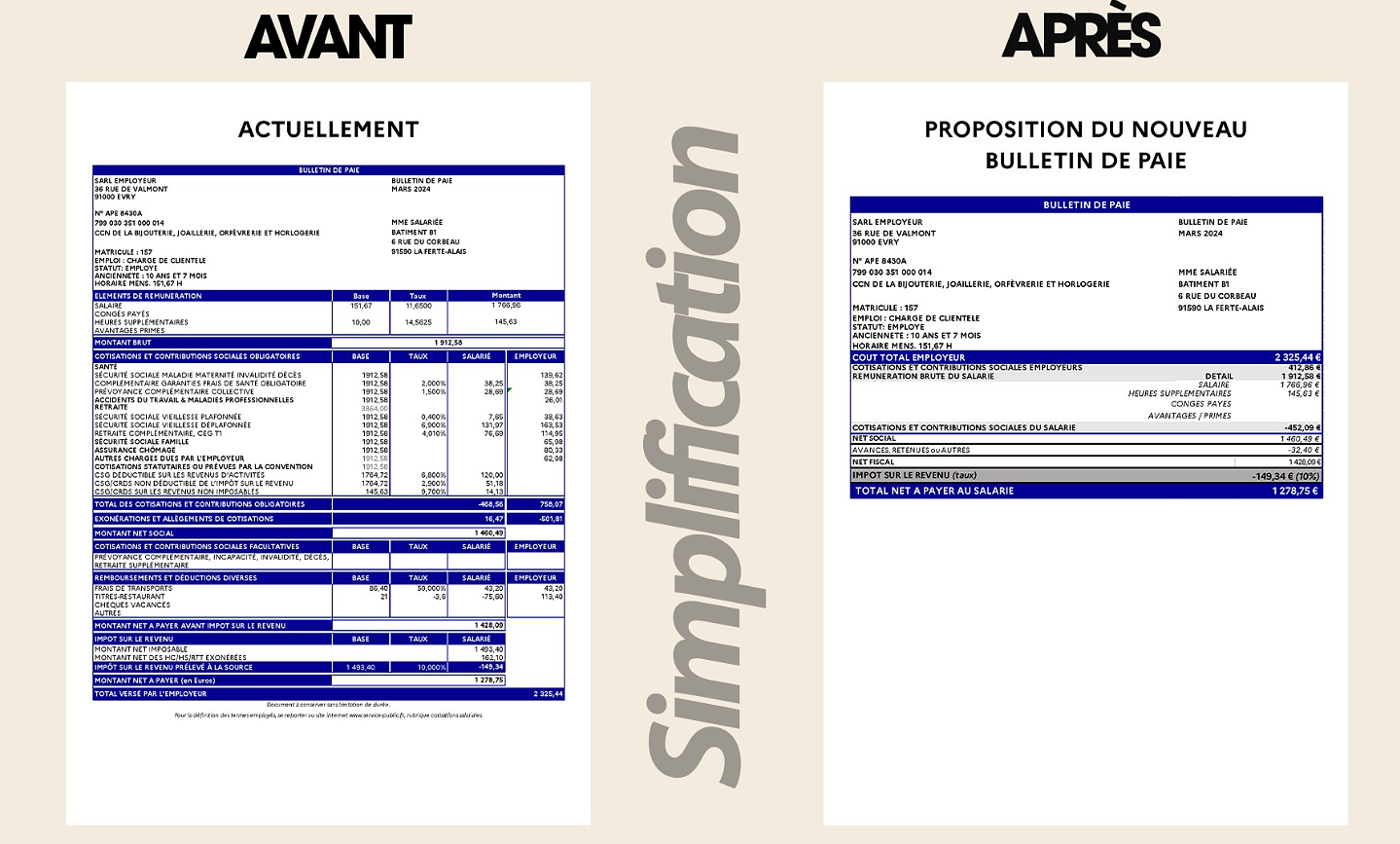

“I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy 25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits

25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan

At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga

Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker

Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops

OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet

Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid

Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid