An academic career, an art history career that was as high as possible, was aspired to. In the museum, in a public collection. There was actually no doubt about it. But things turned out differently. Angelika Arnoldi, a student of art history from the Upper Bavarian Inn Valley, discovered her tendency to convince potential buyers of the quality of a work of art during her practical stays in Paris and New York with the legendary thoroughbred art dealer Serge Sabarsky. Most importantly, she discovered her talent.

Returning to Munich, Angelika Arnoldi got her future husband Bruce Livie interested. The American from Baltimore, Yale and Harvard graduate, a representative of the casual intellectual type from the best circles with a bow tie, welted shoes, great manners, Scottish roots and a DAAD scholarship in Munich, actually gave up his academic career for the art trade .

At the end of 1972 the two opened their gallery on Maximilianstrasse. The magnificent boulevard, today a promenade with the eternally bland flagship stores of international noble designers, was then the hotspot of the gallery scene, i.e. contemporary art. Jahn, Thomas, Friedrich, they and all the other gallery owners have long since fled.

The two newcomers Arnoldi-Livie, then 23 and 26 years old, courageous and self-confident, endowed with the dash of blessed naivety necessary for such undertakings, placed their programmatically still somewhat undecided art trade in between. In their first exhibition, on one of the upper floors behind a Bavarian-bourgeois façade, they showed works on paper by Gustav Klimt. In the second they offered works by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Oskar Schlemmer.

Step by step, they learned the lessons that were essential for success in the art trade. One of the first: In addition to all efforts, luck plays a prominent role. One day, unannounced, trustees from the New York Museum of Modern Art showed up at the door and, in 1973, laid the tiny foundation stone for their gallery to gain transatlantic attention. The second, equally important lesson followed quickly: The constant effort to make discoveries and to increase one's reputation with the unexpected can suddenly turn into blind zeal Connoisseurs presented, waved it off - bitter lesson.

On the other hand, Bruce Livie's great museum tour through the United States was extremely fruitful. He mapped the diverse aspects of the museum landscape, classified the collections and their historical focal points, and established contacts. And he profited, although still young, stylishly as a compatriot. Art historical knowledge and the willingness to continuously learn new things gave him the necessary respect. To this day, Livie acts according to his maxim that trade and research belong together: "We live from what we know".

The Arnoldi livies soon sharpened the company's profile. They traded in old master works, the focus was on German Romanticism through to Impressionism. French and German hand drawing became a specialty and also an affair of the heart. Experience, a good eye and the avoidance of hasty judgments are the basis for the meticulous attribution and dating of a sheet.

International renown was not lacking, the participation in the Tefaf, the queen of all art fairs in Maastricht, and the Salon du Dessin, the demanding and recognized special fair in Paris, did the rest. That's where the important, the powerful collectors gather, that's where the curators and trustees make the pilgrimage, where the best dealer competitors exhibit. A good strategy, so you don't get bogged down in a whirlpool of worldwide, more or less promising trade fair participations.

Over the course of five decades, the focus had continuously shifted overseas. In 1983 Arnoldi-Livie sold Dürer's pen and ink drawing The Good Thief to the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The department for old master drawings had just been set up there. Schinkel's portraits of his children, a triptych from 1817, has been hanging in the St. Louis Museum of Art in Missouri since 1995, instead of – which is not entirely understandable – in the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin.

The two art dealers were not always able to understand the considerations of the curators, although they had a great deal of intuition and perseverance for the complex paths of museum decision-making. Menzel's “Sunday Afternoon in the Tuileries Garden”, for example, once hung in Dresden, but the Albertinum refused to accept the logic of buying it back. Since 2006 the painting has received the attention it deserves alongside Monet's Tuileries motif in London's National Gallery.

In 1983, Livie founded the circle of friends of the Central Institute for Art History in Munich based on the Anglo-Saxon model and led it until 2016. The mostly financially very well-endowed members enjoyed high-quality excursions. When asked why family and trade were not completely relocated to the USA, Angelika Arnoldi-Livie explains that this was always a topic of debate. Since 1988, however, the cozy and representative gallery rooms with a view of the courtyard garden had been set up and had become a permanent contact point for collectors and curators. And would it really have been a good idea to let the two sons grow up in New York?

Of course, there have also been difficult phases in the course of the company's many years of history. But as Angelika Arnoldi-Livie pragmatically states, general economic crises were more beneficial: many a collector had to sell art. And for outstanding works of museum quality, sooner or later a buyer was always found.

In any case, Bruce Livie always advocated having several irons in the fire with his usual composure. Bottlenecks then never became threatening. The sale of Lovis Corinth's sea of flowers "Weißer Flieder", which was passed on to a private collection in 2020, proves that the slow-motion atmosphere of the pandemic was not to the detriment of the art trade.

Both sons followed an art-by-no-case-path into professional life. Caspar, the older one, had decided: "Never go into the art trade and never run a company with your wife." Merging work and family can be exhausting. He studied mechanical engineering and climbed the unsatisfactory career ladder in a Swiss chemical company. He remained connected to art over the years, accompanied his parents to Tefaf, where he promptly met his future wife Marie - and together with her opened the Livie Gallery for contemporary art in the heart of Zurich in 2018.

While the parents are now taking it easy, the young Livies are looking forward to performing with them. At the upcoming Salon du Dessin in Paris (March 22 to 27, 2023) they will use works on paper by artists from both programs to build up a field of tension that spans centuries and quite casually make a strong commitment to art as the center of their lives.

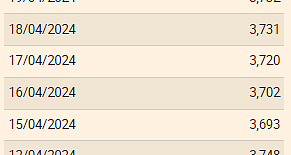

The Euribor today remains at 3.734%

The Euribor today remains at 3.734% Germany: the trial of an AfD leader, accused of chanting a Nazi slogan, resumes this Tuesday

Germany: the trial of an AfD leader, accused of chanting a Nazi slogan, resumes this Tuesday New York: at Columbia University, the anti-Semitic drift of pro-Palestinian demonstrations

New York: at Columbia University, the anti-Semitic drift of pro-Palestinian demonstrations What is Akila, the mission in which the Charles de Gaulle is participating under NATO command?

What is Akila, the mission in which the Charles de Gaulle is participating under NATO command? What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated)

What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated) Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France

Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France Food additives suspected of promoting cardiovascular diseases

Food additives suspected of promoting cardiovascular diseases “Even morphine doesn’t work”: Léane, 17, victim of the adverse effects of an antibiotic

“Even morphine doesn’t work”: Léane, 17, victim of the adverse effects of an antibiotic MEPs validate reform of EU budgetary rules

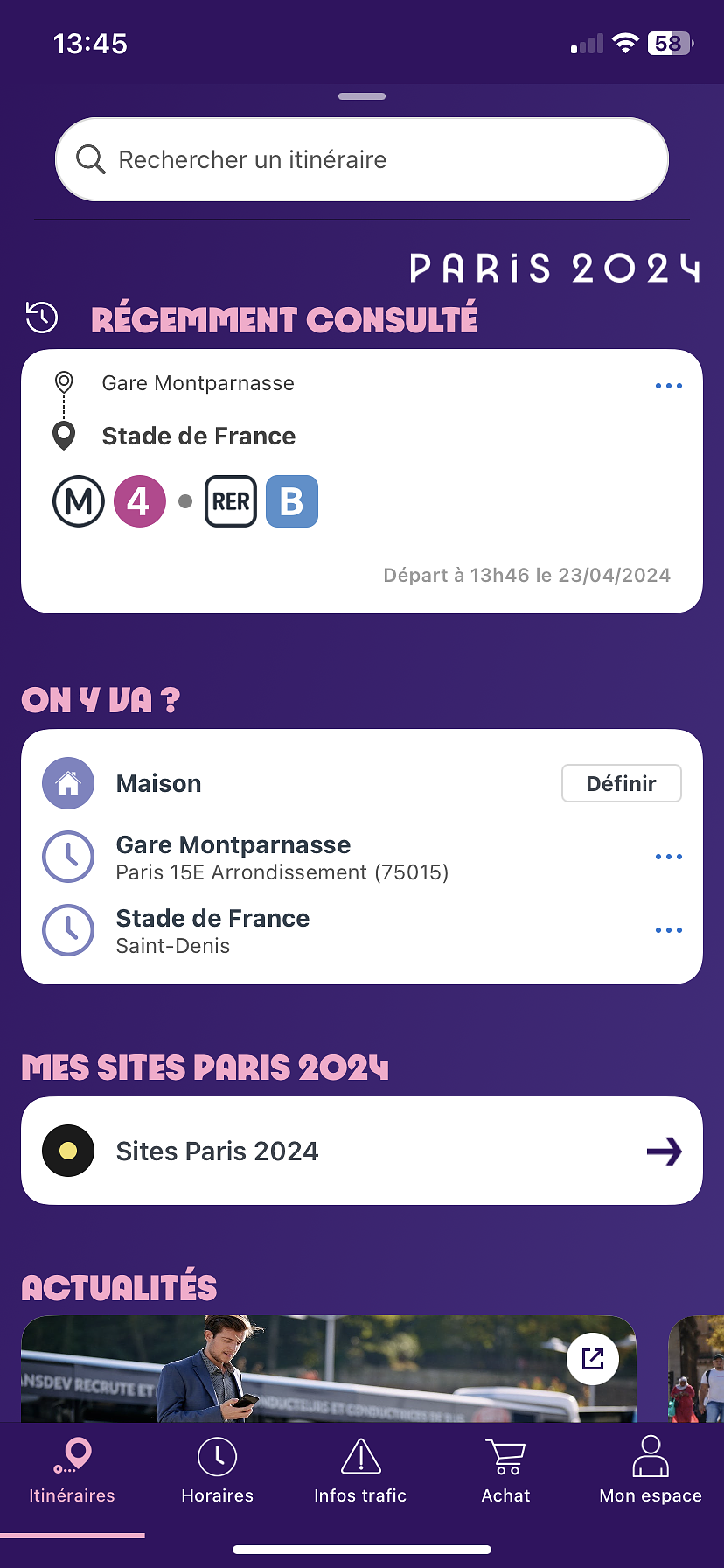

MEPs validate reform of EU budgetary rules “Public Transport Paris 2024”, the application for Olympic Games spectators, is available

“Public Transport Paris 2024”, the application for Olympic Games spectators, is available Spotify goes green in the first quarter and sees its number of paying subscribers increase

Spotify goes green in the first quarter and sees its number of paying subscribers increase Xavier Niel finalizes the sale of his shares in the Le Monde group to an independent fund

Xavier Niel finalizes the sale of his shares in the Le Monde group to an independent fund Owner of Blondie and Shakira catalogs in favor of $1.5 billion offer

Owner of Blondie and Shakira catalogs in favor of $1.5 billion offer Cher et Ozzy Osbourne rejoignent le Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

Cher et Ozzy Osbourne rejoignent le Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Three months before the Olympic Games, festivals and concert halls fear paying the price

Three months before the Olympic Games, festivals and concert halls fear paying the price With Brigitte Macron, Aya Nakamura sows new clues about her participation in the Olympics

With Brigitte Macron, Aya Nakamura sows new clues about her participation in the Olympics Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Serie A: Bologna surprises AS Rome in the race for the C1

Serie A: Bologna surprises AS Rome in the race for the C1 Serie A: Marcus Thuram king of Italy, end of the debate for the position of number 9 with the Blues?

Serie A: Marcus Thuram king of Italy, end of the debate for the position of number 9 with the Blues? Milan AC-Inter Milan: Thuram and Pavard impeccable, Hernandez helpless… The tops and flops of the derby

Milan AC-Inter Milan: Thuram and Pavard impeccable, Hernandez helpless… The tops and flops of the derby Ligue 2: Auxerre leader, Bordeaux in crisis, play-offs... 5 questions about an exciting end of the season

Ligue 2: Auxerre leader, Bordeaux in crisis, play-offs... 5 questions about an exciting end of the season