Hardly any ability seems to be affirmed as uncontroversially today as empathy. Empathizing with others, putting yourself in the shoes of others, broadening your own perspective – what could possibly go wrong? It's the business of literature, of film, if not of any kind of art. It seems all the more radical that the Icelandic Frida Ísberg is now declaring war on precisely that virtue.

Because our present is not only shaped by tangible crises, which include a war, a pandemic and an energy shortage. It's also the era when psychological diagnoses are springing up like magic mushrooms. Just as the categories "toxic", "narcissistic", "traumatic" and "depressive" fit every disorder in case of doubt, at the same time the positive counter-concept becomes a panacea: empathy. Those who are empathetic, i.e. who can empathize with other people, are on the best way to saving the world and their own psyche - so the tenor.

The problem: The hype about empathy leads to a threatening split into particular interests from which no common denominator can be formed, because everything is just "a personal opinion" that one has to understand against one's own subjective horizon of experience. In the comment function on social media you can read things like "No offense meant, just my opinion" or "I see things differently, but you can have your opinion, that's okay". With the insight into the limitations of human perspectives, every conversation is nipped in the bud. Arguments are denigrated as weapons, discussions as struggle.

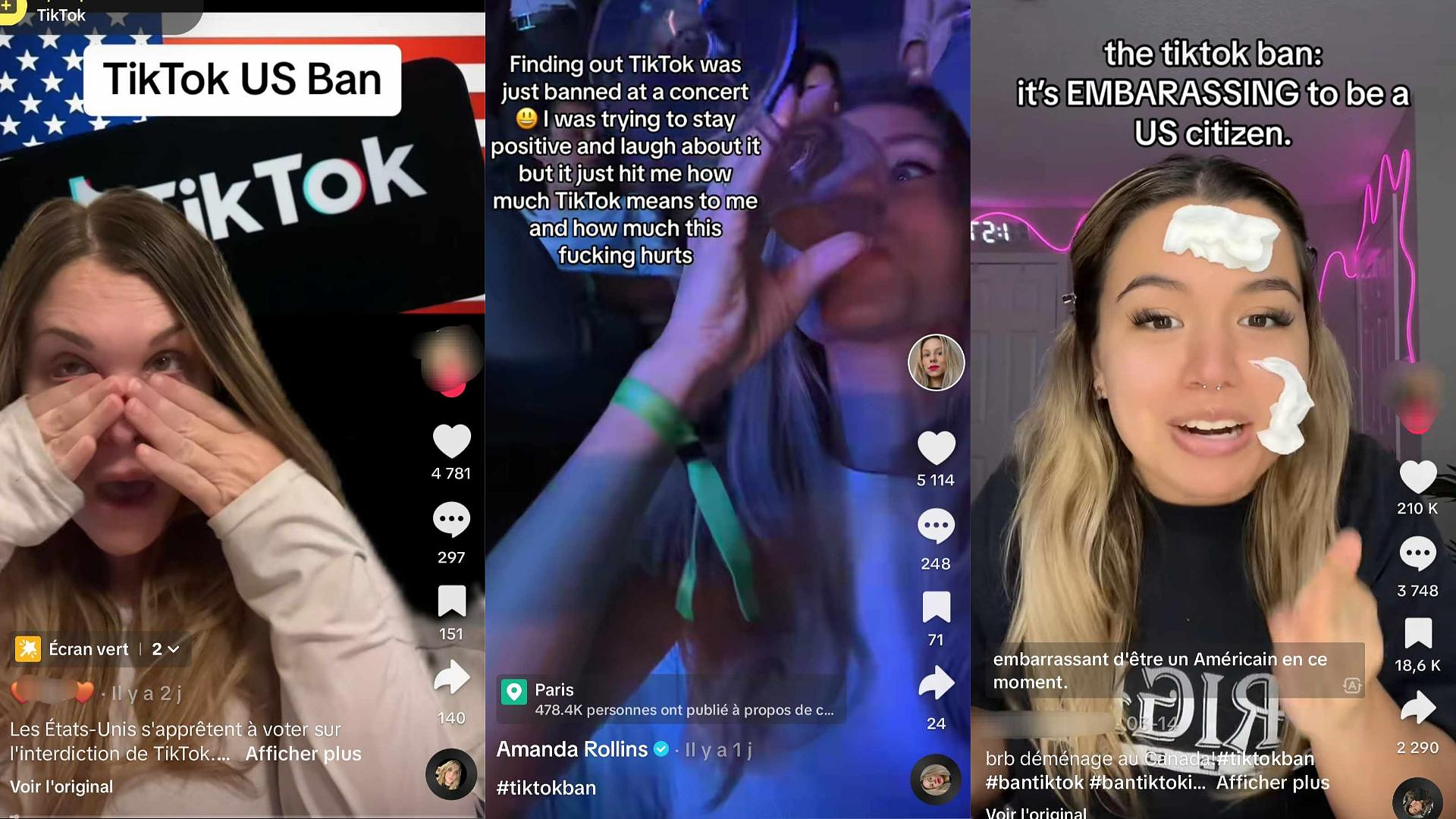

TikTok and Instagram point the way: Videos with so-called “PoV” (“Point of View”; dt.: standpoint) invite you to take other perspectives, no matter how abstruse they may be. Posts in the aesthetics of so-called vulnerability porn, on which weeping faces can be seen in close-up, declare war on a narcissism of strength, but defend themselves with a narcissism of weakness, which is still there perfidious. So is empathy just selfishness in sheep's clothing? After all, even an "I understand what you mean" gets stuck in the comfort of one's ego without making the effort to really engage with the other person - which includes trying to convince.

Frida Ísberg has presented a dystopian theses novel with her award-winning debut “The Marking” (Hoffmann and Campe, from the Icelandic by Tina Flecken, 288 pages, 23 euros), which has now been published in German and illuminates the dark side of the ubiquitous empathy mania. It's about a society in which all citizens have to undergo an empathy test. So-called "unmarked", i.e. people who have not taken or failed the test, are denied access to certain places, such as restaurants, gyms or residential areas. In a society based on transparency and control, those who are not marked are considered untrustworthy, unpredictable and dangerous.

You don't have to do any interpretative contortions to feel reminded of the empathy tests of the corona tests - here, too, those who were not tested or not vaccinated were treated as social outsiders and lepers. Ísberg is now making the leap from physical to mental health. There is a paradox behind this: the more mental illnesses are recognized as normal and going to a therapist is being equated with going to the doctor (“If you have a broken leg, you go to the doctor. Then why not do it with a broken heart? ", is a popular saying from the calendar; with Ísberg, the advice flourishes to "talk to a child under the empathy guideline as if it had a vitamin deficiency"), the greater the social pressure to practice uninterrupted mental hygiene.

After all, an imbalanced mind is not only contagious, it is also costly. “Crime is very expensive for society. A broken person can break ten more people in a relatively short period of time. Violence costs the healthcare system and increases the number of disability pensions. We can no longer afford that,” argues an advocate of the legally anchored marking. Critics, on the other hand, argue that "therapeutic" offers for people who fail the test become "further training camps" and then "extermination camps".

Those who do not undergo emotional training are labeled: “But since I stopped therapy a year ago, people have prejudices, I can really feel how their behavior towards me is changing. It's like I can't get anything done because I'm not working on myself.” With subtle irony, Ísberg flashes going to the therapist as an ambivalent panacea; as an answer to every dilemma, no matter how trivial, one hears the advice: "Find yourself a therapist!" The only alternative is pills to stimulate the hormones. Emotional competence has advanced to become a core ability of the trustworthy citizen - help is provided if necessary.

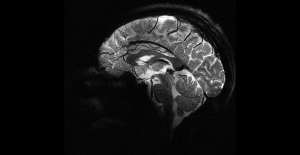

In order to determine the empathy values, a helmet is put on the test object. While he is being shown various films, the device measures "brain activity, dilation of the pupils, heartbeat and perspiration" for 20 minutes. The protagonists try desperately to increase the number of their tears from test to test. What is measured is: their potential to laugh or cry with them. And not only at the sight of a person who resembles the test subject, but also at the sight of a black woman, an Asian man and a woman in a burqa.

What started as voluntary tests for members of parliament to make sure the country wasn't run by psychopaths quickly grew into a public registry where anyone can look up who passed the test and who didn't. Though coming out publicly leads to bullying and suicide, in Ísberg's astute prognosis, politicians invoke maximizing overall happiness through prophylaxis.

In addition to an allegory of state and digital surveillance in the context of the pandemic, "The Mark" also provides a specific critique of the empathic praise of empathy in the psychological age. Because with the call for compassionate citizens comes the call for political correctness. In order to prevent someone from making a hurtful comment on Twitter in the first place, it is better to undergo a therapeutic cleansing beforehand.

Ísberg exposes the consequences of such a regime, in which emotion reigns in its bureaucratized form, in all its menace through the personal fates of five protagonists: Here, strength is associated with psychopathy, doubt is praised and convictions condemned, profile pictures on social media are considered “as Signs of complacency”, “Fighting as a sign of aggression and stupidity”. "Testosterone and aggressiveness are no longer sinful vices, but downright symptoms of illness." Everyone talks “only in this pandering questioning tone. No one dares to say things clearly anymore because aggressiveness is considered violence”.

Or: “Others have also started to remain silent. To be silent and to listen, to think, to understand both sides and not to dare to take a point of view, because a point of view is generalization and generalization is violence, and therefore it is better to listen and understand than to argue and be right To want to have.” Or to put it another way, by a muzzled critic of the new values: “this consideration and appreciation crap”, “this I-understand-you-I-am-only-a-different-opinion-nonsense”.

The history of philosophical criticism of compassion is as long as the shitstorm under a tweet by J.K. Rowling. Kant distrusted the feeling because of its arbitrariness, Nietzsche suspected it as vain self-aggrandizement. The sociologist Eva Illouz identified the emotional market as a playground for neoliberal goods. And the Germanist Fritz Breithaupt referred to “the dark sides of empathy” in his book of the same name: The supposed virtue of empathy produces fewer positive effects when a hostage identifies with their hostage-taker; or when sadists use their emotional understanding to be more efficient in tormenting others.

Ísberg picks up on all of these arguments, making her novel more of a philosophical exploration than a compelling crime thriller. For example, as an objection to the supremacy of empathy, it says: “Empathy and compassion can be as blind as hate or fear or anger or love. Just as blind as prejudice. Anyone can put on a passionate expression. Everyone can tell their tragic story. Compassion has been instilled in us for generations as a kind of miracle solution, but no generation has yet managed to draw the line between compassion and codependency.”

When the publishing house Hoffmann und Campe announces "The Marking" as a novel that deals with the important questions of our time "with great empathy", this can actually only be understood as irony. Or as proof of your own thesis that the dictatorship of empathy cannot be escaped – not even on the book market.

"Aha! Ten minutes of everyday knowledge" is WELT's knowledge podcast. Every Tuesday and Thursday we answer everyday questions from the field of science. Subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Deezer, Amazon Music, among others, or directly via RSS feed.

Germany: the trial of an AfD leader, accused of chanting a Nazi slogan, resumes this Tuesday

Germany: the trial of an AfD leader, accused of chanting a Nazi slogan, resumes this Tuesday New York: at Columbia University, the anti-Semitic drift of pro-Palestinian demonstrations

New York: at Columbia University, the anti-Semitic drift of pro-Palestinian demonstrations What is Akila, the mission in which the Charles de Gaulle is participating under NATO command?

What is Akila, the mission in which the Charles de Gaulle is participating under NATO command? Lawyer, banker, teacher: who are the 12 members of the jury in Donald Trump's trial?

Lawyer, banker, teacher: who are the 12 members of the jury in Donald Trump's trial? What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated)

What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated) Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France

Vaccination in France has progressed in 2023, rejoices Public Health France Food additives suspected of promoting cardiovascular diseases

Food additives suspected of promoting cardiovascular diseases “Even morphine doesn’t work”: Léane, 17, victim of the adverse effects of an antibiotic

“Even morphine doesn’t work”: Léane, 17, victim of the adverse effects of an antibiotic Orthodox bishop stabbed in Sydney: Elon Musk opposes Australian injunction to remove videos on X

Orthodox bishop stabbed in Sydney: Elon Musk opposes Australian injunction to remove videos on X One in three facial sunscreens does not protect enough, warns L'Ufc-Que Choisir

One in three facial sunscreens does not protect enough, warns L'Ufc-Que Choisir What will become of the 81 employees of Systovi, a French manufacturer of solar panels victim of “Chinese dumping”?

What will become of the 81 employees of Systovi, a French manufacturer of solar panels victim of “Chinese dumping”? “I could lose up to 5,000 euros per month”: influencers are alarmed by a possible ban on TikTok in the United States

“I could lose up to 5,000 euros per month”: influencers are alarmed by a possible ban on TikTok in the United States Dance, Audrey Hepburn’s secret dream

Dance, Audrey Hepburn’s secret dream The series adaptation of One Hundred Years of Solitude promises to be faithful to the novel by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

The series adaptation of One Hundred Years of Solitude promises to be faithful to the novel by Gabriel Garcia Marquez Racism in France: comedian Ahmed Sylla apologizes for “having minimized this problem”

Racism in France: comedian Ahmed Sylla apologizes for “having minimized this problem” Mohammad Rasoulof and Michel Hazanavicius in competition at the Cannes Film Festival

Mohammad Rasoulof and Michel Hazanavicius in competition at the Cannes Film Festival Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Serie A: Bologna surprises AS Rome in the race for the C1

Serie A: Bologna surprises AS Rome in the race for the C1 Serie A: Marcus Thuram king of Italy, end of the debate for the position of number 9 with the Blues?

Serie A: Marcus Thuram king of Italy, end of the debate for the position of number 9 with the Blues? Milan AC-Inter Milan: Thuram and Pavard impeccable, Hernandez helpless… The tops and flops of the derby

Milan AC-Inter Milan: Thuram and Pavard impeccable, Hernandez helpless… The tops and flops of the derby Ligue 2: Auxerre leader, Bordeaux in crisis, play-offs... 5 questions about an exciting end of the season

Ligue 2: Auxerre leader, Bordeaux in crisis, play-offs... 5 questions about an exciting end of the season