From the big and global it goes into the small, intimate. After “Krass” – the portrait of a larger-than-life powerful man from 2021 that stretches from Naples to Cairo, from the Roman Empire to the Middle Ages – Martin Mosebach has now written a chamber play. One of the laws of the genre is that every look counts twice here, every word reverberates as if echoed back from the walls.

The first part of "Taube und Wildente", Mosebach's first novel after moving to dtv, is set in southern French light. Marjorie and Ruprecht live in a country house in Provence every summer, La Chaumière. "Own" would be wrong, because it belongs to a family foundation on Marjorie's side, who is the rich heir to a fortune dating back to (Belgian) colonial times, but is not independent, either financially or spiritually: she is ruled by the strict spirit of an upper-class patriarch , who, years after his death, still determines the rules of the property, from the table arrangement to the staff to the artfully maintained neglect that marks the difference to bourgeois perfectionism.

People move in circles that downplay their wealth and draw status awareness from it. Marjorie claims the right to be a brute because she can't tell the difference between truth and wickedness.

Her husband Ruprecht Dalandt, an esthete who runs a renowned small publishing house in Frankfurt, has it twice as difficult, because he is both a guest and host in what he thinks is his own house – he has a new editor named Sieglinde Stiegle and his commercial right hand Allmendiger for a summer Working leave requested in Provence.

At the same time there is family; Ruprecht's stepdaughter Paula from Marjorie's first marriage and her five-year-old daughter Nike; plus Paula's friend, an ambitious but untalented musician, who becomes the preferred victim of Marjorie's meanness: "There are three kinds of pianists, Jewish pianists, gay pianists and bad pianists - what do you belong to?" The newly arrived Editor Stiegle, who thinks Marjorie is her colleague's lover, is given the following poisoned praise at dinner: "You're obviously one of those smart women who don't care about the looks of their partners."

The heartless open-heartedness that is de rigueur in La Chaumière is paired with neurotic reticence. Everyone carries secrets with them. Paula does not want to reveal the father of her child at any price. Marjorie has an ongoing affair with the quirky, powerfully manly estate manager.

Above all, however, Ruprecht is tormented by a misstep that makes him study Dante's visions of hell for his own writing project: seven years ago he experienced the ultimate erotic fulfillment in a forbidden love. "The unexpectedly heavy punishment for what happened was that there should be no after, even if the heart pumped the blood through the vein for years to come."

The oppressively humid south has the climate of a Dantesque ice hell; even humor does not mean closeness and warmth here, but baring of teeth: “But why did so many people like to laugh? After all, who could find funny what one saw and experienced? Everything happened according to well-known and predictable laws, but they were all inevitable. Where was the surprise in that?” It's as if the country house, once built with the blood of exploited peoples, is holding its occupants accountable down to the last link. It is only logical that business matters penetrate to the core of the already fragile bones of a relationship.

Into this reality populated by the living damned, Mosebach now allows painting to penetrate as an alternative draft. Even the setting at the foot of the famous Montagne Sainte-Victoire endows the novel's plot with the aura of art; the house is, according to Allmendiger, the numbers man, of all people, “inserted into a gigantic three-dimensional Cézanne painting”.

A (small) Cézanne also hangs on the walls, along with Georges Braque, Juan Gris, Maurice de Vlaminck – all of these cursed family inheritances – and the eponymous still life “Pigeon and Wild Duck” by the now almost forgotten Frankfurt Academy painter Otto Scholderer. (Of course, the self-confessed anti-avant-gardist Mosebach also provides art-philosophical observations, for example on the concept of kitsch and the derogatory syllable "late".)

When Ruprecht suddenly has an aesthetic awakening experience in front of this hardly noticed picture and the truth of the work of art tears the inauthenticity of his serene intellectual existence like a veil, he sets in motion a chain of events that will soon destroy the entire fragile structure of life: marriage, the family, the house, the publisher. The complicated construct of non-aggression pacts, unspoken agreements, dissimulations and apparent indifference becomes a ruin like the decrepit country house in an autumn storm.

In the second part, set in Frankfurt's autumn and winter, Mosebach lets the summer's emotional outbursts sink into resigned heaviness. But even that is not the last word on the underestimated late work called Ehe. “Where was the surprise in that?” Here, in this painting of a novel executed to perfection in the style of the old masters.

Martin Mosebach: "Pigeon and wild duck". dtv, 336 pages, 24 euros.

Sydney: Assyrian bishop stabbed, conservative TikToker outspoken on Islam

Sydney: Assyrian bishop stabbed, conservative TikToker outspoken on Islam Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases”

Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases” Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK

Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years

In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years WHO concerned about spread of H5N1 avian flu to new species, including humans

WHO concerned about spread of H5N1 avian flu to new species, including humans New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria

New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting

Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence

The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence Bitcoin halving: what will the planned reduction in emissions from the queen of cryptos change?

Bitcoin halving: what will the planned reduction in emissions from the queen of cryptos change? The Flink home shopping delivery platform will be liquidated in France

The Flink home shopping delivery platform will be liquidated in France Bercy threatens to veto the sale of Biogaran (Servier) to an Indian industrialist

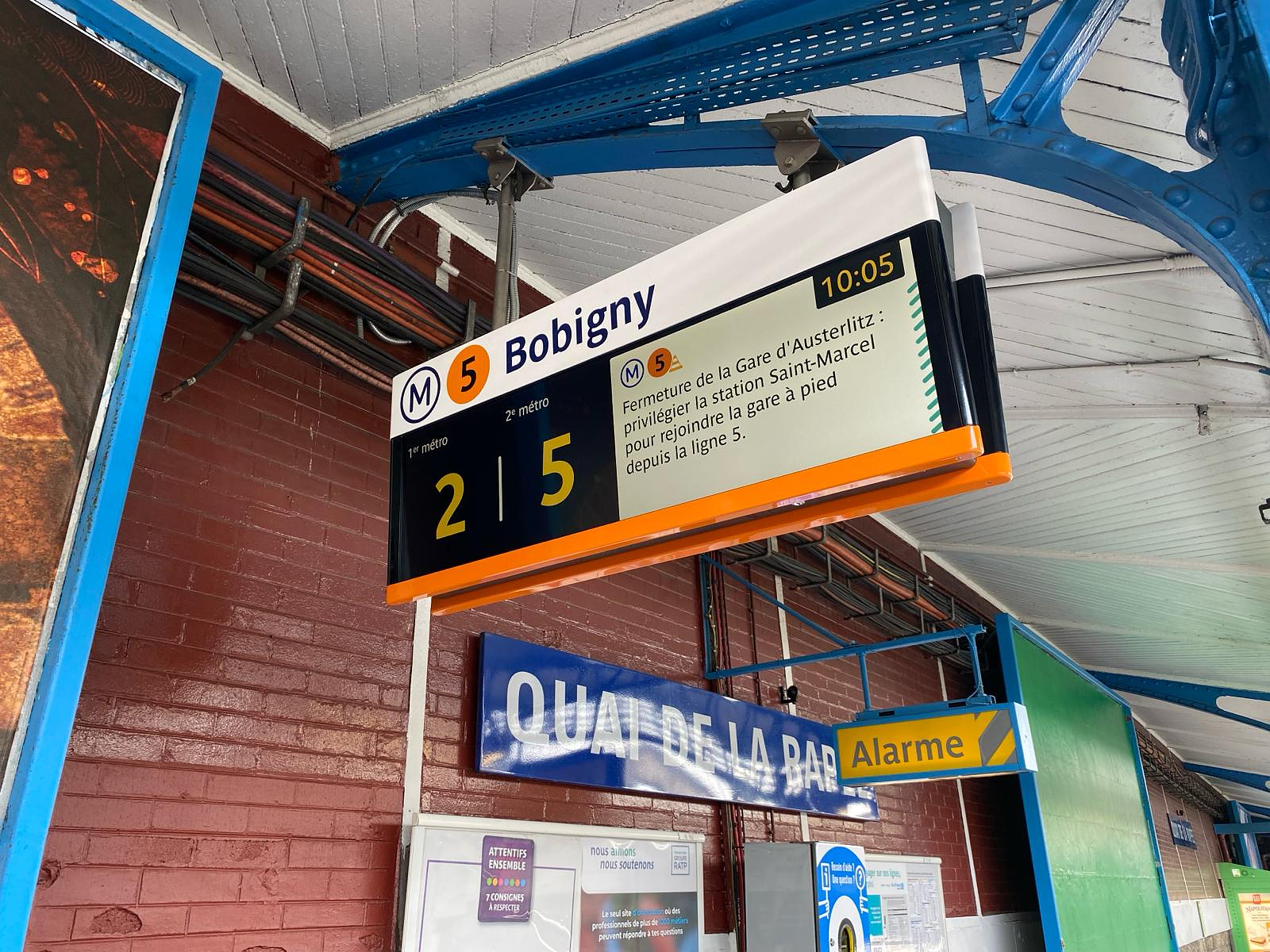

Bercy threatens to veto the sale of Biogaran (Servier) to an Indian industrialist Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF?

Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF? The main facade of the old Copenhagen Stock Exchange collapsed, two days after the fire started

The main facade of the old Copenhagen Stock Exchange collapsed, two days after the fire started Alain Delon decorated by Ukraine for his support in the conflict against Russia

Alain Delon decorated by Ukraine for his support in the conflict against Russia Who’s Who launches the first edition of its literary prize

Who’s Who launches the first edition of its literary prize Sylvain Amic appointed to the Musée d’Orsay to replace Christophe Leribault

Sylvain Amic appointed to the Musée d’Orsay to replace Christophe Leribault Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie

During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Europa Conference League: the semi-final flies to Lille, which loses to the wire against Aston Villa

Europa Conference League: the semi-final flies to Lille, which loses to the wire against Aston Villa Lille-Aston Villa: Cash disgusts Lille, the arbitration too... The tops and the flops

Lille-Aston Villa: Cash disgusts Lille, the arbitration too... The tops and the flops Handball: Les Bleues in the same group as Spain at Euro 2024

Handball: Les Bleues in the same group as Spain at Euro 2024 Europa Conference League: for Létang, Martinez “does not have the attitude of a high-level athlete”

Europa Conference League: for Létang, Martinez “does not have the attitude of a high-level athlete”