Fascism as a concept has never completely disappeared, but it also has booms in which one hears it more or less often. The word is booming at the moment. The Putin system in Russia, with its wars of aggression and racist contempt for non-Russians, is increasingly being interpreted by analysts as the current manifestation of fascism. The Ukrainians call the attackers "racists", a portmanteau of "Russians" and "fascists". And in Italy, a party that has at least fascism in its genes is seizing power. How fascist it still is in real terms is disputed.

Perhaps a classic film about the nature and emergence of that political current in the early 20th century will help with the analysis. "Ordinary Fascism" by Soviet director Mikhail Romm from 1965 is one of those works whose titles have become proverbial. He ironically refers to biological terminology. There is the common porpoise, common viper's bugloss and common octopus. The sexologists Martin Dannecker and Reimut Reiche referred to both in 1974 with their epochal study “The Ordinary Homosexual”.

Romm's film is an essay, the word documentary is too one-dimensional for that. The director cuts together recordings from Nazi propaganda films. A sarcastic comment is heard from the off. Sometimes it's suitably cruel cold, but often it's very funny. For example, when Hindenburg gets lost in a military formation. Or when the creation of the Hitler "rhombus" is documented. The dictator liked to fold his hands protectively over his privates (perhaps subconsciously to protect his only remaining testicle), and his paladins aped him in doing so. The passages about Nazi art also strike an ironic tone, although even more intelligent contemporaries noticed that a certain similarity to monumental Soviet art was unmistakable.

Romm had nothing to do with this monumentality. He belonged to the generation of directors who brought Soviet cinema to a second late heyday in the 1960s. Unlike Mikhail Kalatosov with "I am Cuba" or the early Andrei Tarkovsky with "Iwan's Childhood" or "Andrei Rublow", Mikhail Romm did not work with plan sequences, i.e. very long shots without a cut. Rather, he went back to the montage technique that Sergej Eisenstein used to revolutionize cinema in the 1920s, i.e. quick cuts in which images – often large and close-ups – are juxtaposed and commented on.

The film still opens up original perspectives for historical fascism today. However, this is hardly the way to get to the bottom of today's fascism, which has undergone numerous metamorphoses in East and West.

Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases”

Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases” Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK

Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years

In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years Iran's attack on Israel: these false, misleading images spreading on social networks

Iran's attack on Israel: these false, misleading images spreading on social networks New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria

New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting

Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence

The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence Amazon invests 700 million in robotizing its warehouses in Europe

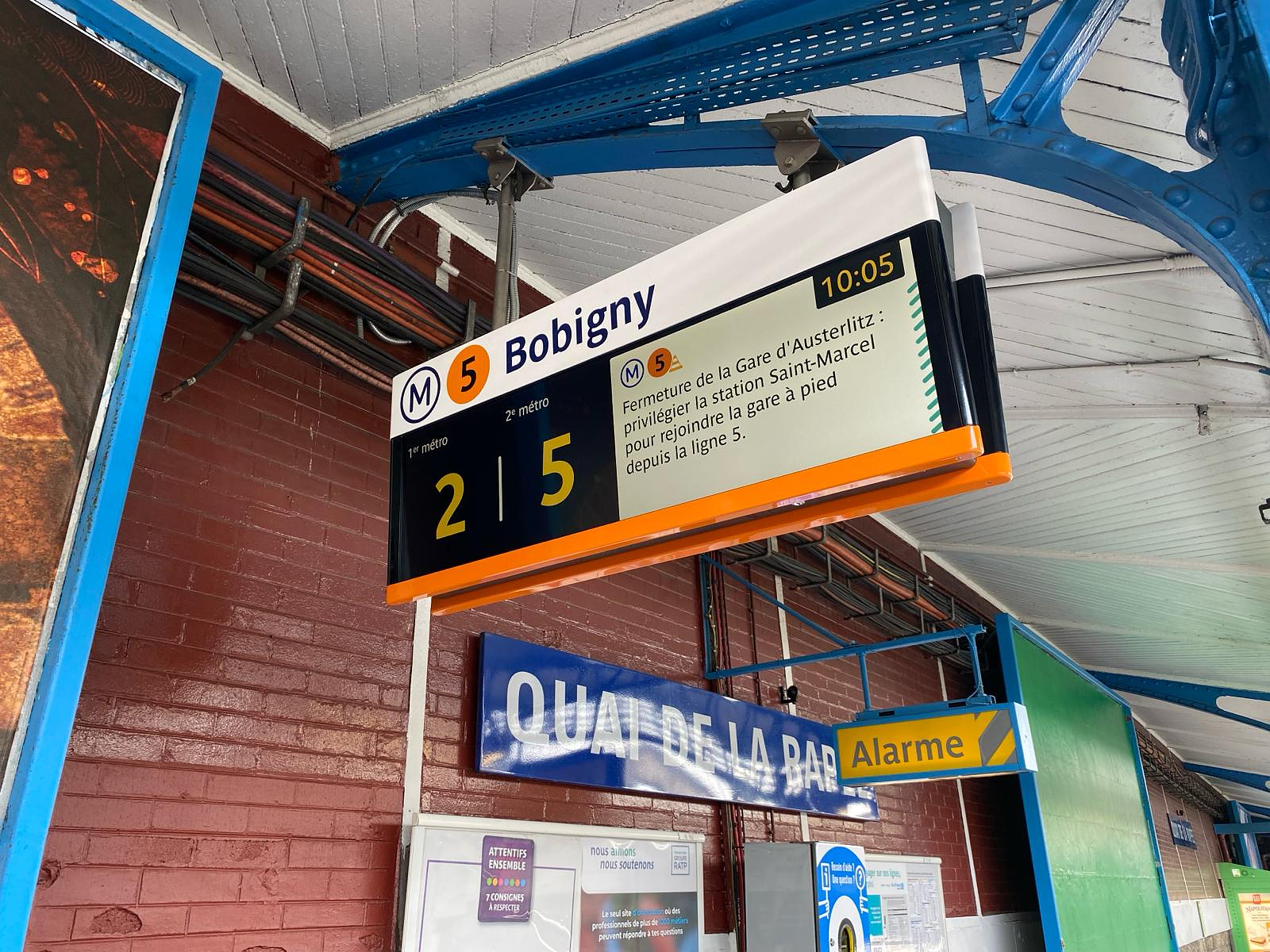

Amazon invests 700 million in robotizing its warehouses in Europe Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF?

Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF? Transport in Île-de-France: operators are pulling out all the stops on passenger information before the Olympics

Transport in Île-de-France: operators are pulling out all the stops on passenger information before the Olympics Radio audiences: France Inter remains firmly in the lead, Europe 1 continues its rise

Radio audiences: France Inter remains firmly in the lead, Europe 1 continues its rise Russian cyberattacks pose a global “threat”, Google warns

Russian cyberattacks pose a global “threat”, Google warns A new Lennon-McCartney duo, more than 50 years after the Beatles split

A new Lennon-McCartney duo, more than 50 years after the Beatles split The Curse vs Immaculée: two thrillers but only one plot

The Curse vs Immaculée: two thrillers but only one plot Mathieu Kassovitz adapts The Beast is Dead!, the comic book about the Second World War and the Occupation by Calvo

Mathieu Kassovitz adapts The Beast is Dead!, the comic book about the Second World War and the Occupation by Calvo Goldorak 'has never lived so much as now'

Goldorak 'has never lived so much as now' Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie

During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Champions League: semi-final schedule revealed

Champions League: semi-final schedule revealed Serie A: AS Roma extends Daniele De Rossi

Serie A: AS Roma extends Daniele De Rossi Ligue 1: hard blow for Monaco with Golovin’s premature end to the season

Ligue 1: hard blow for Monaco with Golovin’s premature end to the season Paris 2024 Olympics: two French people deprived of the Olympic Games because of a calculation error by the international federation?

Paris 2024 Olympics: two French people deprived of the Olympic Games because of a calculation error by the international federation?