Once upon a time there was a little Czech boy named Tomáš Straussler. He was born in the town of Zlín; his father worked as a doctor for the shoe factory, Bata, which practically owned the town. When the Germans invaded in 1938, the patriarch who owned the shoe factory behaved very humanely. He called the Jewish company doctors together in his living room and offered them the opportunity to emigrate to Singapore or Kenya - Bata had branches in both places. Tomáš's father chose Singapore. A mistake.

Because shortly after Tomáš, his little brother and his parents arrived in Singapore, the city — which was still part of the Empire at the time — was overrun by Japanese troops. Tomáš, his brother and his mother saved themselves on a ship that went to Bombay, his father was supposed to follow on the next ship - but he never arrived. His ship was attacked by Japanese planes, those passengers who did not drown or burned were shot in the water by machine gun fire.

Tomáš, his little brother and their mother settled in Darjeeling at the foot of the Himalayas. The two boys attended an American boarding school founded by missionaries and quickly forgot their Czech. They were raised as Christians. Her widowed mother became the manager of the local Bata shoe factory. But she had worries: she and her boys were still citizens of the Czechoslovak Republic, which no longer existed — there was no security for her and her small family. A Major Kenneth Stoppard, who was serving in the British Army in New Delhi, visited Darjeeling on holiday and took an interest in her. He invited her to dinner, gave her flowers and chocolate.

The two were married in November 1945 at St. Andrew's Church in Calcutta; The fact that she was Jewish was naturally not emphasized in the atmosphere at the time. The family settled in England. Tomáš was no longer called Tomáš, but Thomas, so in short: Tom. At the age of 27 he wrote a play about two minor characters in a famous play by William Shakespeare: "Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead". The joke of his play is not only that it degrades Hamlet, the Prince of Denmark, to a secondary character: the two main characters never understand what is actually going on.

In the final scene, they stumble to their execution still clueless. The play became a roaring success, making its author famous overnight. And Tom Stoppard has been an integral part of British theater life since the 1960s. He wrote plays and screenplays (including the screenplay of "Shakespeare in Love"), he is friends with Steven Spielberg. He's a patriotic Englishman, he was a Tory at least for a while, he belonged in London without reservation.

He didn't hide the fact that he was actually Tomáš Sträussler from Zlín, but he forgot — or pushed it out of his memory. From the 1970s he rediscovered his Czech identity because he fraternized with the anti-communist dissidents behind the Iron Curtain: Václav Havel, who later became President, became a close friend. But his Judaism? Although Tom Stoppard was circumcised, he was also baptized and had not the faintest idea about Jewish rites and symbols. For a long time, he also didn't know what had happened to his family. It was only later that he found out that his father's parents had been deported first to Theresienstadt and then to Riga and murdered. His mother's parents came to Auschwitz, as did two of her sisters. And she never told her sons about it.

As an old man, Stoppard has now rediscovered his Jewish origins. And in a certain sense the novelist Daniel Kehlmann is to blame for that. The young colleague from Vienna told Tom Stoppard about his paternal family: Kehlmann's grandmother survived because her husband bribed a non-Jew to perjure himself — he claimed he was her father. Many other members of Kehlmann's paternal family were deported and murdered. Tom Stoppard sat down and started to read: about Gustav Klimt and Gustav Mahler, the Evian Conference, where Jews were prevented from emigrating to other countries, about Theodor Herzl, anti-Semitism in Vienna and Sigmund Freud. Then he sat down and wrote the play Leopoldstadt, which premiered in London in 2020 — just before the pandemic. Now the play, directed by Patrick Marber, has landed on Broadway with a bit of a delay.

The play takes place in a single room, the salon of the Merz family, who naturally no longer live in Leopoldstadt but have moved to the Ringstrasse. One is assimilated, one is baptized, one belongs, and Vienna — it is the year 1899 — is the center of the universe. The first scene of the play is a tumultuous and hilarious Christmas celebration: young Filius commits a faux pas when he attaches a Magen David — a Jewish six-pointed star — to the top of the Christmas tree. Grandma Emilia (Bertsy Aidem) comments, "I don't have a problem with young Jesus because he had no idea what was going on, but I have a weird feeling about Easter eggs." Later, the whole family will celebrate the Seder night. Her son Hermann Merz (David Krummholtz) is Catholic and also a textile manufacturer: "We are Austrians," he says. He considers Zionism, with which his brother-in-law, the unworldly mathematician Ludwig Jakobovicz, is flirting, to be outright nonsense.

The play advances in great leaps in time: the children of the first act are adults in the second act. We see the year 1924, the war is lost and Austria is a republic. Then comes the onset of catastrophe: 1938, the "Anschluss". A Nazi (Corey Brill) enters the living room where the family is huddled together — already packed on their suitcases and in coats — and barks at them: “You’re not at home here anymore.” An English journalist, whose surname was Chamberlain, of all people is called (Seth Numrich), understands exactly that the path can now only lead into the abyss. He marries Nellie (Tedra Millan) and adopts their young son Leo (Michael Deaner) so they can escape to London. While the Nazi is yelling, little Leo cuts himself on a shard, his hand is bleeding profusely; an uncle who is a doctor stitches up his wound without anesthesia.

"Leopoldstadt" is at the same time a typical and a totally atypical Tom Stoppard piece. Typical insofar as one witty dialogue follows the other and the punch lines just chase each other. Atypical, however, is that the play is about a family; So far Stoppard had only been marginally interested in this. Two main themes are repeated in “Leopoldstadt”: one is mathematics — Ludwig, the unworldly, likeable eccentric, would love to find a proof for the Riemann conjecture, i.e. to bring order to the chaos of prime numbers. The other main theme is the string game, which different adults and children play together in this piece. What both themes have in common is that they are about beauty, symmetry, a pattern; and of course that pattern — that deeper meaning — doesn't exist in the story. What there is is only the wound in the hand.

The last scene in "Leopoldstadt" takes place ten years after the end of the war. The Austrians have managed to evade responsibility with the shameless claim that they were Hitler's first victims; the walls in the room that was once the Merz family's living room are black. The Nazis stole the Klimt painting that once hung there. Three survivors gather in the living room: Aunt Rosa (Jenna Augen), who had emigrated to New York before the disaster; Nathan (Brandon Urowicz), who survived Auschwitz; and the now-adult Leo (Arty Froushan), the English journalist's son. Leo is the most interesting character in this scene because he can't remember anything.

He does not consider himself a Jew. He thinks he has nothing to do with this whole complicated and horrific and sad story. But then Nathan tells him about how his uncle stitched up his wound that night in 1938. And suddenly Leo remembers and starts to cry. You don't have to be a psychoanalyst to understand how much Tom Stoppard is in the character of Leo. As he burst into tears, Broadway's Longacre Theater — where New York audiences had greeted every joke with grateful laughter — grew very quiet. In this silence, one or the other may have thought about the fact that Vienna without Jews was once as unthinkable as New York without Jews is today.

At the end, Aunt Rosa brings the family tree to the salon on a piece of paper. Leo reads out the names, Rosa tells each family member what has become of him or her. The last word of the piece is “Auschwitz”.

Sydney: Assyrian bishop stabbed, conservative TikToker outspoken on Islam

Sydney: Assyrian bishop stabbed, conservative TikToker outspoken on Islam Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases”

Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases” Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK

Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years

In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years WHO concerned about spread of H5N1 avian flu to new species, including humans

WHO concerned about spread of H5N1 avian flu to new species, including humans New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria

New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting

Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence

The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence Bitcoin halving: what will the planned reduction in emissions from the queen of cryptos change?

Bitcoin halving: what will the planned reduction in emissions from the queen of cryptos change? The Flink home shopping delivery platform will be liquidated in France

The Flink home shopping delivery platform will be liquidated in France Bercy threatens to veto the sale of Biogaran (Servier) to an Indian industrialist

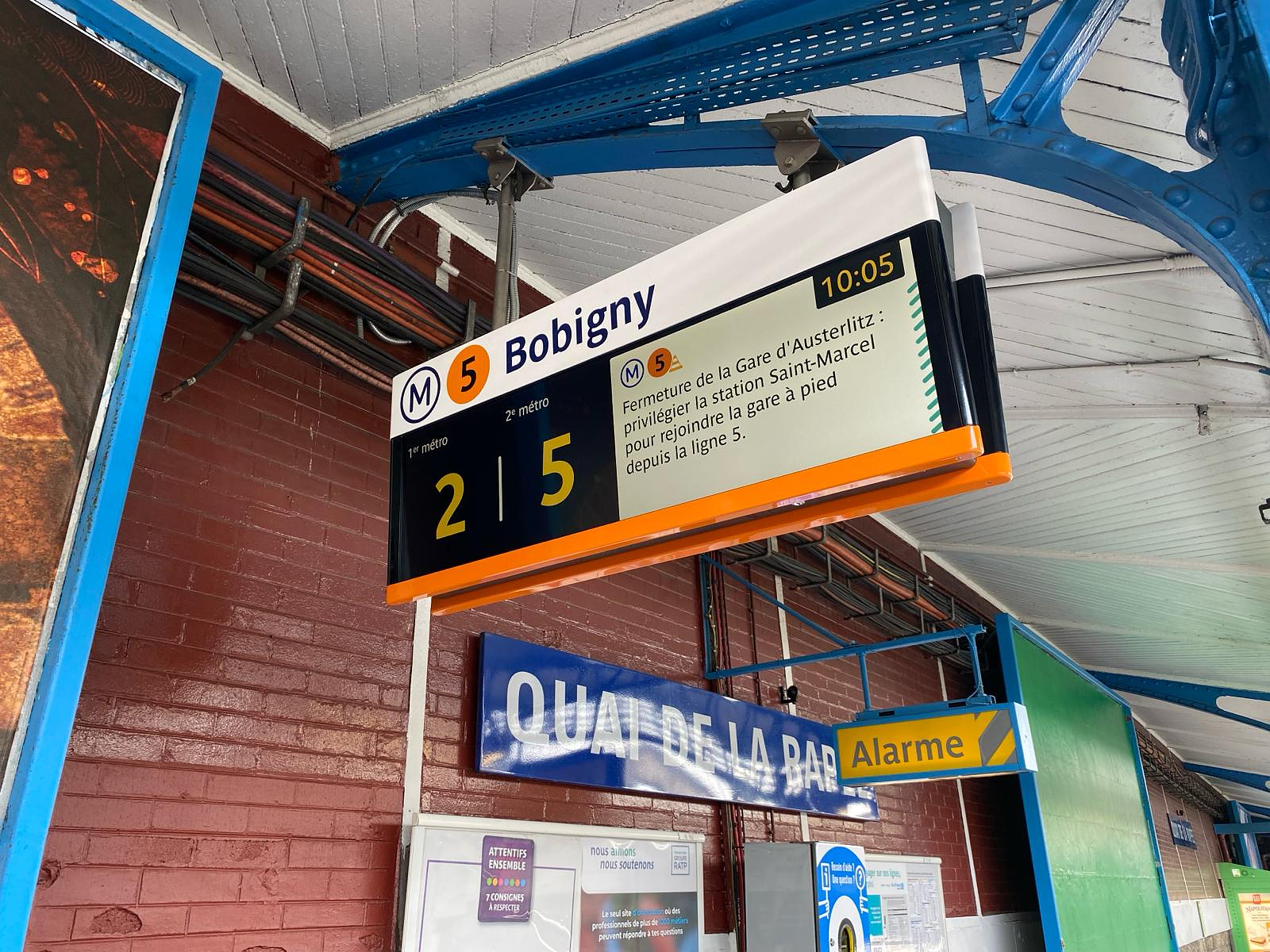

Bercy threatens to veto the sale of Biogaran (Servier) to an Indian industrialist Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF?

Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF? The main facade of the old Copenhagen Stock Exchange collapsed, two days after the fire started

The main facade of the old Copenhagen Stock Exchange collapsed, two days after the fire started Alain Delon decorated by Ukraine for his support in the conflict against Russia

Alain Delon decorated by Ukraine for his support in the conflict against Russia Who’s Who launches the first edition of its literary prize

Who’s Who launches the first edition of its literary prize Sylvain Amic appointed to the Musée d’Orsay to replace Christophe Leribault

Sylvain Amic appointed to the Musée d’Orsay to replace Christophe Leribault Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie

During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Europa Conference League: the semi-final flies to Lille, which loses to the wire against Aston Villa

Europa Conference League: the semi-final flies to Lille, which loses to the wire against Aston Villa Lille-Aston Villa: Cash disgusts Lille, the arbitration too... The tops and the flops

Lille-Aston Villa: Cash disgusts Lille, the arbitration too... The tops and the flops Handball: Les Bleues in the same group as Spain at Euro 2024

Handball: Les Bleues in the same group as Spain at Euro 2024 Europa Conference League: for Létang, Martinez “does not have the attitude of a high-level athlete”

Europa Conference League: for Létang, Martinez “does not have the attitude of a high-level athlete”