Pure black, he managed to bring out the light. An uncompromising creator, the painter Pierre Soulages, who died on Wednesday October 26 at the age of 102, never stopped exploring the mysteries of this pigment and painting. L'Express invites you to rediscover the great interview that Pierre Soulages gave us on the eve of his 90th birthday, in 2009.

Some artists look like their work. Such is Pierre Soulages. When he welcomes you on the threshold of his house-workshop in Sète, facing the Mediterranean, next to the marine cemetery where Paul Valéry rests, the impression is striking. From the last colossus of post-war abstraction, an imposing presence immediately emerges. Bright. Which, under the exterior of an apparent austerity, goes hand in hand with an extreme courtesy, a culture and a curiosity which are the prerogative of the honest man but also of an artist apart. Friend of Giacometti, Hartung and Rothko, the master of the "outrenoir" will have known how to remain faithful to the same line, all in the quest for an art of the essential, without, however, ceasing to innovate. Praise of the light in the shadows, black work conceived in solitude. L'Express met him on the eve of his 90th birthday and the retrospective - the fourth in France - that the Pompidou Center is devoting to him.

Pierre Soulages, in the middle of his black and streaked canvases on which, always changing, the light is reflected.

- (c) Raphaël Gaillarde/RMN/Grand Palais

L'Express: The retrospective which will open at the Center Pompidou is the largest devoted to an artist living in this museum. What will it show?

Pierre Soulages: The term retrospective has always displeased me. I never liked looking back. The important thing is the canvas that I will do tomorrow. I prefer to speak of an overall exhibition. It deploys sixty-three years of my journey: from the works of my beginnings, from 1946, to the recent large-format polyptychs - some dating from 2009. It is part of a continuity: this taste for black, which has accompanied me since childhood. When I was given colors to paint, I preferred to dip my brushes in the inkwell. No doubt my attraction to this color dates back to that time. The exhibition will begin with walnut husks, tars... Banal, vulgar materials, but which I liked.

So you have remained faithful to the same aesthetic line?

Yes, but with a break, in 1979, around which the scenography of the exhibition revolves. This break happened incidentally while I was painting. I was then convinced that I would miss the painting I was working on and, despite this conviction, I continued to paint. Something extremely strong in me pushed me to it. I no longer painted with the black with which the canvas was entirely covered, but with the light reflected by the different surface states of the black. This light coming from the dark went beyond the simple optical phenomenon. It upset me. It was at this time that, on the model of the terms "outre-Rhin" and "outre-Manche", which designate other countries, I invented the word "outrenoir". A way of designating, here too, another country. Another mental field than the one reached speaks simple black.

You are often considered the black demon-chrome painter. Listening to you, this is a misunderstanding.

Absolutely ! You have to see with your eyes, and not with what you have in your head. In reality, my work is monopigmented but the opposite of monochrome. A room halfway through the exhibition will, I hope, clear up this misunderstanding. My canvases will be hung in this space where the floor, walls and ceiling will also be black. Thanks to this device, we will see that, in my paintings, it is a matter of reflected light, transformed and transmuted into black. What interests me is exploring the possible variations in the surface states of black. And, with great economy of means, to play intensities at different times. When you think about it, black is fundamental in the history of painting. Three hundred and forty centuries ago, men came down to paint in the total darkness of caves and paint with black. Isn't that disturbing?

You constantly refer to the light emanating from your paintings. Does your research resemble a metaphysical quest?

Not for me. But we can say that black is the color of our origin. Before being born, we are in darkness. Then we see the day and we go towards the light. This is what the Rosicrucians thought. For metaphysical reasons, Robert Fludd, a Rosicrucian, made the first black square, in 1617. It was not Malevich, in 1915, as is often believed.

French painter Pierre Soulages poses in front of his works during the "Soulages 21st Century" exhibition at the Villa Medici in Rome, March 1, 2013

afp.com/Gabriel Bouys

If not by its metaphysical dimension, how to define a work of art?

One day, at the Louvre, I was overwhelmed by a Mesopotamian sculpture. I wondered what I had to do with the man who did this centuries ago: I don't know his ideas, we don't share the same culture or the same religion. I then understood that my interest was not focused on what the work itself represented but was due to the strong presence that emanated from it, linked to the physiognomic qualities of its forms and not to an "illusionist" attempt. to restore appearances. An art without presence is decoration. I've always gone that way.

What about the size, which is very material, of your works? You have long favored large formats.

I also favored - I analyze it a posteriori - verticality. Very early on, I left the easel to paint on the floor, but I always thought and saw my paintings standing. I abandoned the standard commercial frames and preferred to decide myself the dimensions and proportions of my canvases. In general, I chose irrational, more energizing aspect ratios. For example, the one between the diagonal and the side of the square. I find it more pleasing to the eye.

Parallel to your exhibition at the Pompidou Center, Henri Loyrette, the director of the Louvre, offered to hang one of your works in a room of the museum. What is the interest for you, a contemporary artist, of confronting yourself with the great masters?

I have chosen a room that I particularly like, that of the first Italian Renaissance, next to The Battle of San Romano, by Paolo Uccello, which I have always placed among the highest masterpieces of the paint. My canvas will be hung on a wall facing the windows, so that it will reflect the light. In this room also reigns the Maestà, by Cimabue, whom I admire enormously. When you enter, you only see her. There is no question of comparing such foreign works to each other. However, installing one of my paintings in such a place makes sense. Indeed, it is at this time that the transition between Byzantine painting and the "illusionist" technique which leads to perspective takes place. To these two conceptions of space is added that of an abstract painting like mine. The light coming from the golden backgrounds of the Maestà also reminds me of the space encountered in my "outrenoir" painting. In both cases, it comes towards the viewer, creating a space in front of the painting.

Works of art can therefore echo through the centuries?

That's what I thought the first time I saw a Picasso exhibition, at the end of the 1930s. My classmates thought it was rubbish. Me, I was not shocked. I was immediately impressed and interested. I saw in it a link with the primitive arts. It was not so far from the medieval enamels of Conques. Guernica is very close to the Apocalypse of Saint-Sever!

A person looks at "Outrenoir" by painter Pierre Soulages in the museum dedicated to him in Rodez, March 28, 2014

afp.com/PASCAL PAVANI

You developed ties with the United States very early on and counted great American painters among your friends. Did these meetings have an influence on your career?

I exhibited in 1949 in New York, with four other French abstract painters. It was a total flop. But everyone saw us. I had several solo exhibitions at the Kootz gallery and I regularly participated in exhibitions in different museums, including the MoMA, which was still called the Museum of Modern Art at the time. It was not until much later, in 1957, that I went to the United States. Pollock was no longer there but then I met De Kooning, Motherwell, Kline... And Rothko, with whom the first meeting was stormy. He assaulted me at a party, and my response was such that he invited me to lunch at his house the next day. Thus began our friendship, from a spat. Later, I got to know Newman well too. We all had in common to do abstract painting on large formats. But these meetings were not decisive and did not influence me. I had already been exhibiting for more than ten years. My influences are to be sought far elsewhere. Rather on the side of Romanesque painting, prehistoric art.

Are you sensitive to other forms of expression?

I love theatre, architecture, cinema...Citizen Kane thrilled me. I had filmmakers as collectors: Charles Laughton, Otto Preminger, Clouzot, among others. Today, I am less free of my time. I also work a lot in my workshop. What I do is demanding, requires concentration and physical effort. Poetry, on the other hand, has always accompanied me.

With a predilection for a particular genre?

From poets of the Middle Ages to contemporaries. I particularly appreciate one of the first troubadours, Guillaume d'Aquitaine, and in particular one of his poems, which I have made my aesthetic profession of faith. It is about "pure nothing", a perpetual dissatisfaction, comparable to that of the artist, and the rejection of theories. All things that have always guided me. I have often said it: "It's what I do that teaches me what I'm looking for." This led me to change my perception of painting, as with the "outrenoir". When you know what you are going to do, you are an artisan. This is not my conception of artistic creation. In the same way, when I was asked to make the stained glass windows for the abbey church of Conques, I had to invent a new glass in order to best respect the natural light and the spirit of the place. You have to know how to stay curious.

Will the future Soulages museum, which will open in 2012 in Rodez, your hometown, be based on this philosophy?

In fact, I wanted it to show, in particular through the various episodes in the making of the stained-glass windows in Conques, the role of chance in the creation and in the invention of new techniques. An approach based on research, where the unknown has its part. If we keep our eyes open, the unexpected is always possible. And can become decisive. I have often said that I am against artists' museums, which are too often similar to mausoleums. A museum must be alive. I accepted this project on another condition: that a space of 500 m² be created to host temporary exhibitions.

Is the creation of this museum a form of consecration for you?

No, I never looked for anything like that. More than 100 major museums around the world have already acquired my works. If I was lucky enough to be recognized very early on, in 1948, it was thanks to a group exhibition that traveled through Germany. And the first art historian to enter my studio, the same year, was American: James J. Sweeney, curator of the Museum of Modern Art. The French, at first, swallowed me wrong. In Paris, people noticed that I existed because foreigners were interested in my painting. My first major personal exhibition in France - Malraux was then Minister of Culture - took place in 1967, at the National Museum of Modern Art. But it came after Germany, Holland, Switzerland... Moreover, the preface to the catalog specified that, if I was thus honored, it was as an ambassador of French painting abroad. !

This did not prevent you from becoming the most expensive living French artist. One of your paintings was sold a few months ago at Sotheby's for 1.5 million euros.

That people like my painting, I'm delighted. But art as a business does not concern me. What does it mean to be the most expensive French painter? The market wants that. I don't like biennials any more, where all the artists fight behind their country's flag, like at the Olympic Games. Art is not a competition, with a first and a second. Each artist is unique, irreplaceable. Neither is a work a means of communication. It is something much deeper, which goes to the essential.

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation

Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application

Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application “I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing

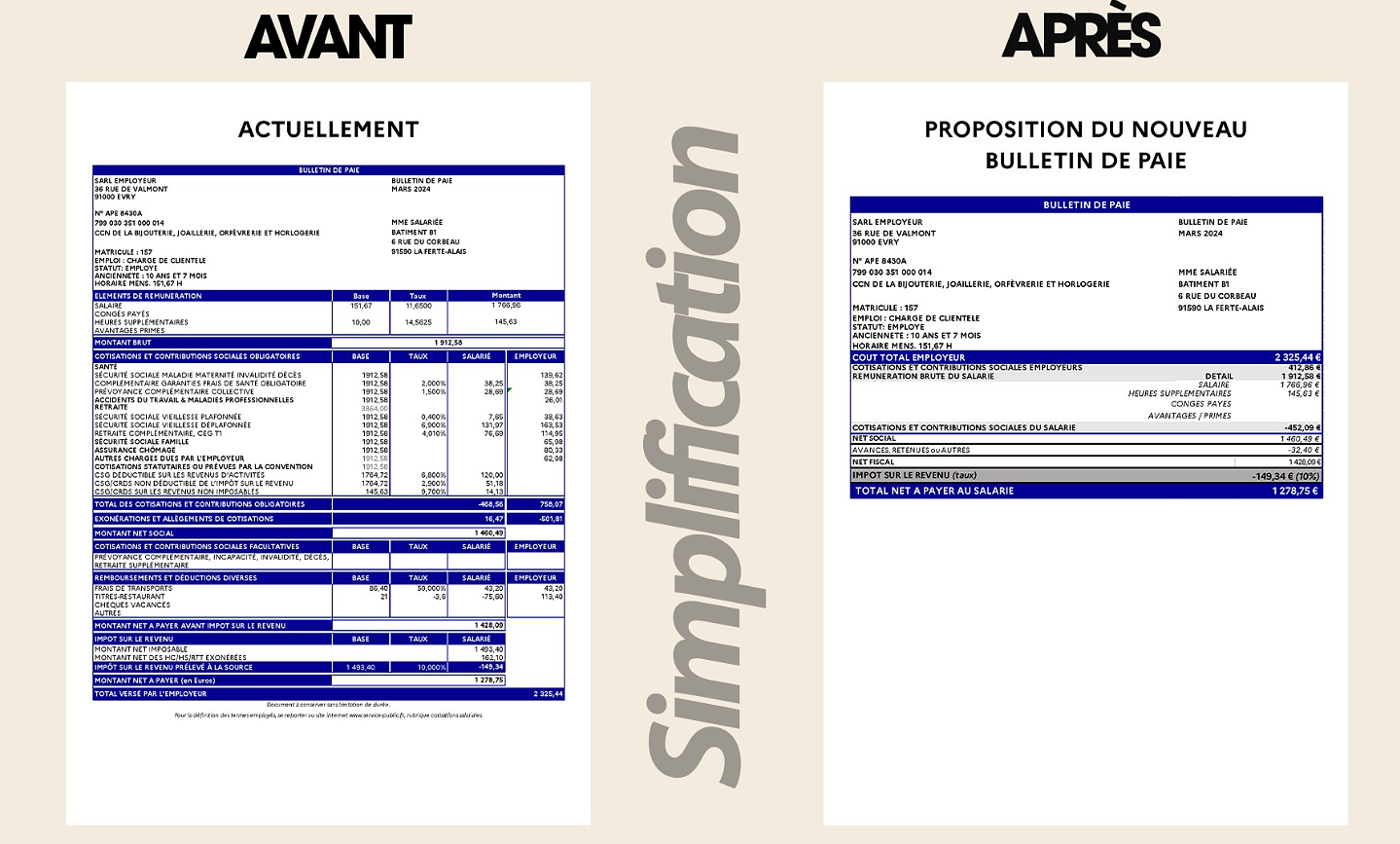

“I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy 25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits

25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan

At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga

Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker

Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops

OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet

Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid

Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid