The Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza should have been open long after the cornerstone was laid 20 years ago. Now it should be this year that the world's largest museum for archeology will finally open. There would definitely be a good spot for the bust of Nefertiti in the huge building within sight of the pyramids.

If Berlin would give them up. Nefertiti is the tourist magnet on Museum Island. In the Neues Museum, the colored limestone bust from around 1350 BC has its own cabinet, where hundreds of thousands of people can look at it, take pictures and share it on social media. Her North African face is an advertising face of German cultural pride, just as the Italian Mona Lisa in the Louvre also smiles for France.

The return of the portrait head was repeatedly demanded. In particular, the Secretary General of the Egyptian Antiquities Administration and interim minister, Zahi Hawass, was downright obsessed. Even after his dismissal in 2011, the archaeologist with the cowboy hat did not rest, most recently he wanted to start a petition to bring him home in the summer of 2022. After her discovery by the Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt, the pharaoh was illegally taken out of the country, i.e. stolen.

The Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation (SPK) sees itself as the legal owner. She persistently points out that it was a "scientific excavation" in 1912 and that a "division of finds, which was common at the time, was agreed upon in return for the financing". Documents testified "clearly and unequivocally" that "Egypt had no legal claims".

Now Saraya Gomis blew into the horn of Hawass. The State Secretary for Diversity and Anti-Discrimination in the Berlin Senate Department for Justice told the “Tagesspiegel” that, in her personal opinion, “the Nefertiti bust must be returned”. In the interview, she extended her generosity to the Pergamon Altar, which can also be seen on the Museum Island, in the 2nd century BC. but had been erected over today's Turkish city of Bergama.

And it was not illegally broken off by the German archaeologist Carl Humann and taken to Berlin, says SPK President Hermann Parzinger to WELT, but had already been destroyed. Humann "saved" the reliefs built into a castle wall and "executed them legally in coordination with the Ottoman Empire". According to Parzinger, there are no official demands for the return of Nefertiti or the Pergamon Altar, nor can he “imagine that this is an attitude of the Senate”.

Berlin State Secretary Saraya Gomis has spoken out in favor of returning the bust of Nefertiti and the Pergamon Altar. "There were never any demands for return," emphasizes Prof. Hermann Parzinger, President of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, in the WELT interview.

Source: WORLD

But the demand was a pinprick in an increasingly moral debate. Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock and Minister of State for Culture Claudia Roth had just used the restitution of the foundation's own Benin bronzes, which had been legally acquired at the time but came from a raid by the British colonial power in the then Kingdom of Benin, for a modest appearance in Nigeria. However, the future of the bronzes is uncertain, as is that of many artefacts from Africa, which are to be restituted on the recommendation of a report by art historian Bénédicte Savoy published in 2018.

Provenance research, a long-suppressed duty of museums, has become essential, even if it means property has to be disposed of. However, instead of preserving vested interests (which is required by law for state collections) there is increasingly an esoteric letting go in the name of reparation (and the calming of private sensitivities).

But what justifies letting go of cultural assets? Legal violations or already sluggish feelings when looking at objects from unlawful contexts? In some ethnological museums one can literally feel how happy the curators are to hand over objects contaminated by colonialism. And does the political will to abolish discrimination result in a right to restitution for exhibits that could be felt to be out of place?

Diversity can hardly be achieved if cultural assets can only be seen where they come from or, as the zeitgeist calls, where they belong. Museums should resist political opportunism. Especially if they want to be a "third place", they not only have to endure controversies, but initiate them or at least moderate them courageously.

The British Museum, of all things, is likely to set a precedent, the centerpiece of which – the “Elgin Marbles” from the frieze of the Parthenon temple on the Acropolis – is claimed by Athens. London has so far refused to return it. They tell “a unique story about the humanity we all have in common”.

Now one reads of “complex conversations” and some of the sculptures could become permanent loans “sooner rather than later”. In return, Greece plans to loan other ancient works of art to Great Britain. Cultural exchange can thus be understood as a contemporary barter transaction.

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation

Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application

Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application “I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing

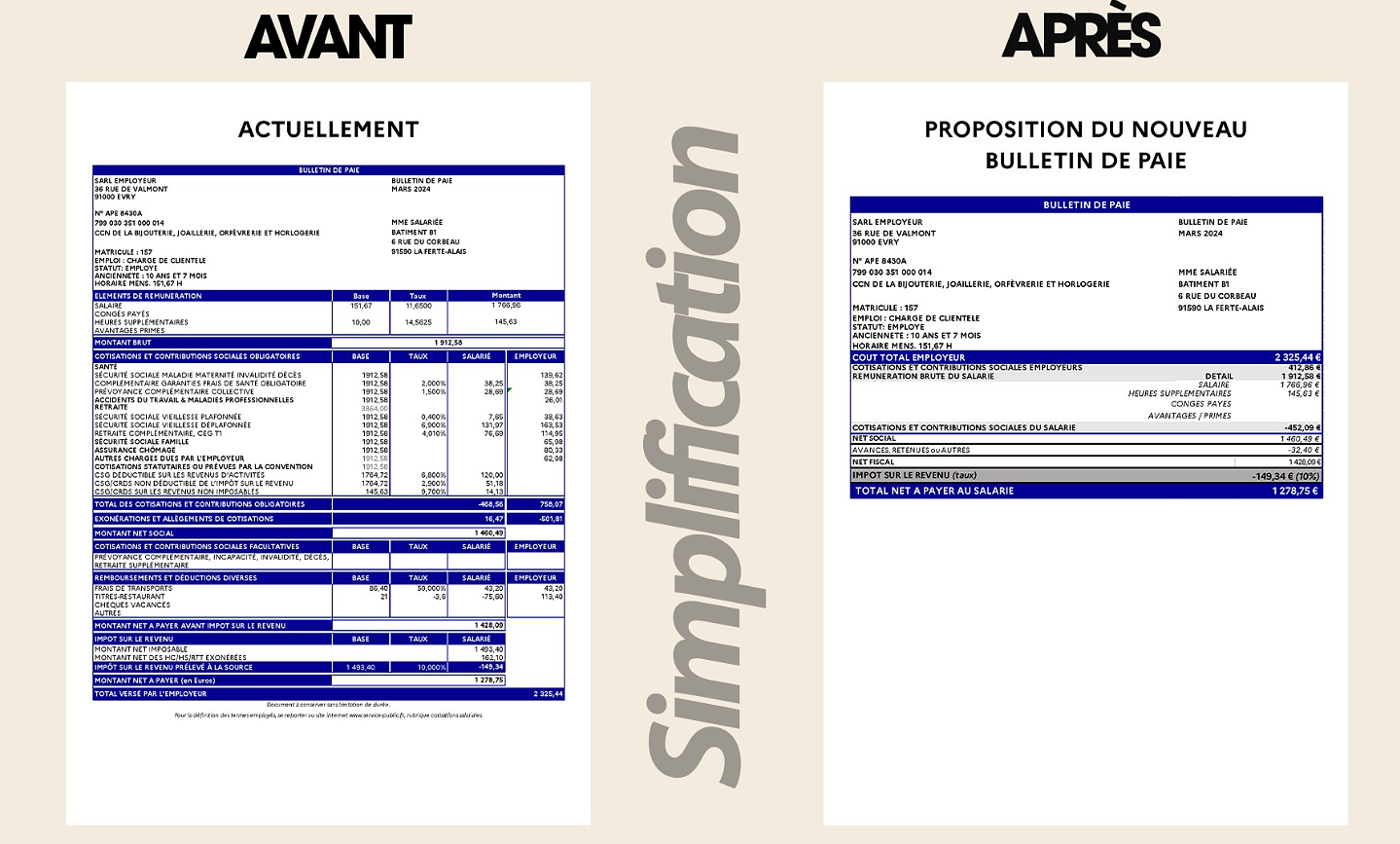

“I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy 25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits

25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan

At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga

Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker

Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops

OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet

Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid

Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid