According to a top researcher, it is time to rethink the entire way we approach preschool.

Dale Farran is a half-century old and has been studying early childhood education. Her most recent scientific publication made her question everything she believed she knew.

"It took a lot soul-searching and a lot reading the literature to find plausible explanations for it."

She refers to the results of a study that lasted over a decade. There were 2,990 children from low income families in Tennessee who applied for free prekindergarten programs. The lottery selected some, while others were denied. This is the closest thing to a controlled, randomized trial in real life -- the gold standard for scientific proof of causality.

The Tennessee Pre-K Debate: Spinach vs. Easter Grass

NPR ED

The Tennessee Pre-K Debate: Spinach vs. Easter Grass

Farran and her Vanderbilt University co-authors followed both sets of children through sixth grade. As expected, children who attended pre-K scored higher in school readiness at the end of their first academic year.

However, after third grade they did worse than the control group. They were even worse by the sixth grade. They scored lower on tests, were more likely be in special education and were more likely get in trouble at school, including suspensions. Farran says that while in third grade, we had negative effects on one of three state achievement tests. In sixth grade, we saw the same effect on all three -- math science and reading. "In the third grade, we saw effects on one type suspension, which was minor violations. But, in sixth grade, we see it on both major and minor suspensions."

That's right. This study found that a state-wide pre-K program taught by licensed teachers and housed in public schools had a statistically significant, measurable negative effect on the children.

Farran didn't expect it. She didn't like it. She didn't like it. However, her study design was so strong that she couldn’t explain it.

"This is the only randomized controlled trial of a pre-K in statewide. I know people are upset and don't want this to be true."

It's not a good time to share bad news

Early childhood advocates are in a difficult time when they hear bad news about public preschool. The federally funded prekindergarten program for children aged 3 and 4 years old was a key component of President Biden’s social agenda. Talks are being held to revive it from the deadlock over the "Build Back Better” plan. Preschool funding has increased in recent years. It is now funded in some degree in 46 states. Around 7 out 10 4-year-olds are now enrolled in some academic program. This enthusiasm is based in part on research dating back to the 1970s. James Heckman, an economist, was awarded the Nobel Prize for his research that showed substantial long-term returns for investment in carefully designed programs.

It's been said that experts and policymakers have known for decades that giving a 4-year old who is living in poverty a lot of story time and block playing will increase their chances of becoming a productive, high-earning citizen.

What went wrong with Tennessee?

One study does not necessarily mean the end. Pre-K research continues to be mixed. A working paper, not yet peer-reviewed, was published in May 2021 that examined Boston's preK program. Farran's study was similar in size, it used a quasi-experimental design that relied on random assignment and followed up with students for many years. The study showed that preschoolers had better disciplinary records, were more likely to graduate high school, take the SATs, and go to college. However, their test scores did not show any difference.

Farran believes that a citywide program offers more quality control opportunities than a statewide one. The program in Boston spent more per student and was also mixed-income, while the program in Tennessee is only for low-income children.

What went wrong in Tennessee? Farran's ideas are challenging in every way. How teachers are trained, funded and where they are located. Everything from where the bathrooms are to how they're prepared.

Farran is, in short, rethinking her preconceptions about quality pre-K.

Are children in poverty entitled to the same education as those who are wealthy?

"One of my biases that I didn't examine in myself was the idea that children from low-income families need a different kind of preparation than children from higher-income families.

She is talking about teaching children basic skills. Worksheets to trace letters and numbers. A teacher gives a 10-minute lecture to 25 students who must sit still and listen. Only five may be paying attention.

She explains that families with higher incomes aren't choosing this type of preparation. "And why would you assume that we should train children from lower-income families sooner?"

Farran points out the fact that families with a lot of money tend to choose play-based preschool programs that incorporate movement, art, and music. Open-ended questions are asked to children and they are listened too.

Farran says this is not the case in schools with many poor children. Farran believes that teachers talk a lot but rarely listen to their students. Farran believes that this is partly due to the fact that many teachers are licensed in teaching prekindergarten through fifth grade, and sometimes even prekindergarten to eighth grade. Their training is very limited and does not focus on the youngest learners.

Another bias she challenges is that teacher certification is synonymous with quality. "Three large studies, including one from 2018, have not shown any correlation between licensure and quality.

Put a bubble in the mouth

Farran published a study in 2016 based on her observations in Tennessee pre-K classrooms, similar to the ones included here. The largest portion of her day was spent in transition. This simply means that children are moved around the building.

This is partly an architectural problem. Private preschools and home-based daycares are often designed with small bodies in mind. Bathrooms are located just outside the classrooms. The classroom is also a great place to eat with your children. There is also an outdoor playground with equipment that can be used by short-sighted children.

These same programs can be made more difficult by being offered in public schools.

"So, if you're in an elementary school older than the one you are currently attending, the toilet will be down the hall. Farran says that you need to get your children out and line them up, then wait. The same goes if you need to use the cafeteria. It's a walk through the halls. "

Farran's most fascinating conjecture is that this need to control could be the reason for the additional discipline problems she observed in her latest study.

"I believe children aren't learning internal control. They are actually learning an almost allergic reaction to the external control they have at school.

This means that if you reprimand or suspend children for doing normal child stuff at four years old, it could backfire later on as the children view school as a place with unreasonable expectations.

Other research has shown that school discipline can have a disparate impact on racial relations. Studies have shown that Black children in preschool are disciplined less often than those in higher grades. Farran's study of 70% of the children was white and found that there were interactions between race, gender, discipline problems, and even attendance at preschool.

Preschool Suspensions Are Real and That's Not OK with Connecticut

From here, where to go

COVID-19 has highlighted and intensified the child care crisis in America. Progressive policymakers and advocates have been trying for years to increase public support for child-care by "pushing down" the existing public schools system using the teachers and buildings.

Farran is a fan of the alternative direction New York City has taken: a mixed-delivery program that offers slots for children aged 3 and 4. Some children attend public preschool for free in existing non-profit day care centers, others in Head Start programs, and some in traditional schools.

Farran's research reveals that the greatest lesson is that pre-K has been asking too much, based on early results of what were basically showcase pilot programs. She says, "We want a miracle cure."

"Who would have thought you could give a 4-year old from an impoverished home 5 1/2 hours per day, nine months of preschool and close the achievement gap to send them to college at higher rates?" She asks. "I mean, why? Why are we putting so much pressure on pre-K programs?

She believes that letting children play can actually lead to better results.

Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases”

Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases” Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK

Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years

In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years Iran's attack on Israel: these false, misleading images spreading on social networks

Iran's attack on Israel: these false, misleading images spreading on social networks New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria

New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting

Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence

The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence Amazon invests 700 million in robotizing its warehouses in Europe

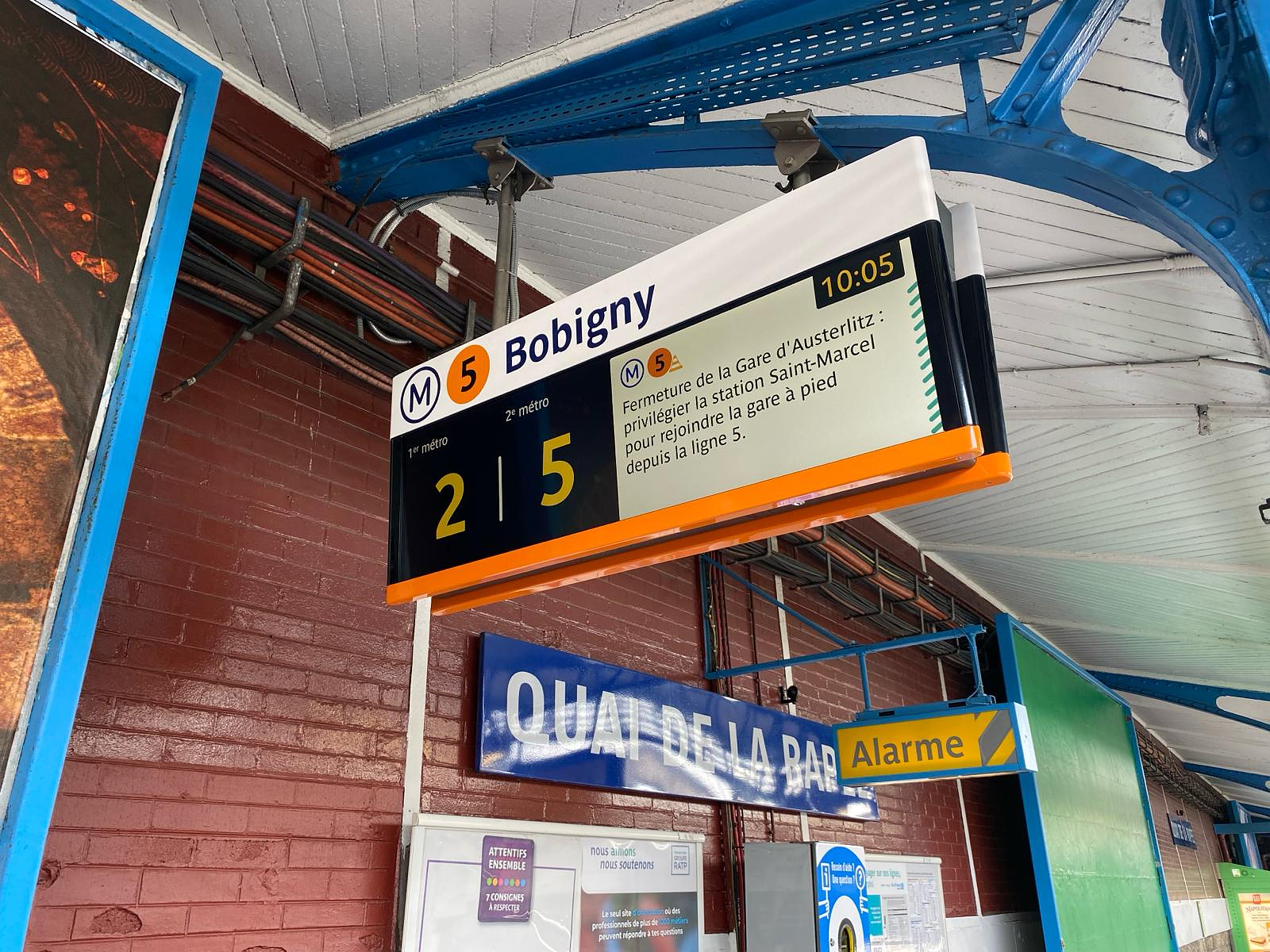

Amazon invests 700 million in robotizing its warehouses in Europe Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF?

Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF? Transport in Île-de-France: operators are pulling out all the stops on passenger information before the Olympics

Transport in Île-de-France: operators are pulling out all the stops on passenger information before the Olympics Radio audiences: France Inter remains firmly in the lead, Europe 1 continues its rise

Radio audiences: France Inter remains firmly in the lead, Europe 1 continues its rise Russian cyberattacks pose a global “threat”, Google warns

Russian cyberattacks pose a global “threat”, Google warns A new Lennon-McCartney duo, more than 50 years after the Beatles split

A new Lennon-McCartney duo, more than 50 years after the Beatles split The Curse vs Immaculée: two thrillers but only one plot

The Curse vs Immaculée: two thrillers but only one plot Mathieu Kassovitz adapts The Beast is Dead!, the comic book about the Second World War and the Occupation by Calvo

Mathieu Kassovitz adapts The Beast is Dead!, the comic book about the Second World War and the Occupation by Calvo Goldorak 'has never lived so much as now'

Goldorak 'has never lived so much as now' Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie

During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie Europeans: Glucksmann denounces “Emmanuel Macron’s failure” in the face of Bardella’s success

Europeans: Glucksmann denounces “Emmanuel Macron’s failure” in the face of Bardella’s success These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Champions League: semi-final schedule revealed

Champions League: semi-final schedule revealed Serie A: AS Roma extends Daniele De Rossi

Serie A: AS Roma extends Daniele De Rossi Ligue 1: hard blow for Monaco with Golovin’s premature end to the season

Ligue 1: hard blow for Monaco with Golovin’s premature end to the season Paris 2024 Olympics: two French people deprived of the Olympic Games because of a calculation error by the international federation?

Paris 2024 Olympics: two French people deprived of the Olympic Games because of a calculation error by the international federation?