The air war made Germany the country it is today. The wide lanes of streets from the 1950s to 1970s, which in German inner cities invite you to enjoy ignoring the speed limit - even if it's only between traffic lights - are the aftermath of the carpet bombing that was dropped in World War II. What the British and Americans had started was then completed by planners with their vision of a car-friendly city. The historical reasons why our cities look the way they do have largely been forgotten 88 years after the end of the war.

The origin of the many words that fell from heaven into our language is also befuddled by a similar historical amnesia. An exhibition in Munich now gives reason to think about whether such forgetfulness is actually dangerous - or perhaps the completely normal, harmless course of language development. In the Flugwerft Schleissheim, a branch of the Deutsches Museum, it is “bomb weather. Air War and Language”. It is a tour of the expressions and idioms that air warfare and aviation have brought to the German language since at least World War I.

From that early period comes, for example, verfranzen, a mostly reflexive verb used with the meaning "to get lost, to get lost, to wander around". In aviation, the navigator was nicknamed Franz, and the pilot was called Emil. This resulted in the verb verfranzen no later than 1915. In the memoirs of Manfred von Richthofen, the "Red Baron", it says about an unsuccessful mission: "So we completely covered ourselves in glory. First 'fray' and then smash the box!"

As with many other expressions, the military origins of verfranzen have long been “under the radar” of the speaker, to use a phrase that exhibition curator Rolf-Bernhard Essig uses in the catalog and whose origin in air warfare is still relatively well known to many people. The original meaning of kamikaze or low-flying aircraft is similarly well known, but has long been used much more frequently in the figurative sense of “self-destructive actors” and “mentally handicapped people”.

Even with boostern, which entered mainstream vocabulary during recent vaccination campaigns, the original conceptual content is still relatively present because it has been explained so often. The booster is a jump-start rocket, with which the required runway length of 1200 meters could be reduced.

But who still thinks of Hitler's blitzkriegs when he announces that he is devastated? The figure of speech in the sense of "sad to death, deeply saddened" or "completely shattered" is quite young. At first, it was only occasionally written that something was very concretely devastated - such as the harvest after a thunderstorm or broken parts of an ancient ruin. Since the late 1930s, the frequency of use of the phrase has increased abruptly many times over. The reason is probably the stereotypical almost daily use in Wehrmacht reports or in news about one's own successes or those of the allies. The destruction of the enemy air force on the ground was one of the core elements of blitzkrieg warfare. From 1939 onwards one read and heard sentences like: "During attacks on airfields in south-east England, several enemy aircraft were destroyed on the ground and two British aircraft were shot down over their own airport."

The word blockbuster, which is also used quite cluelessly today, comes from the vocabulary of the Germans' opponents of the war. It came into German in the late 20th century to mean "expensive, complex, much-advertised and mostly successful cinema film". It is also used in this sense in English. The name of the once globally successful video chain Blockbuster, which has now been ruined by streaming, alludes to this. But when the band The Sweet had their hit “Blockbuster” in 1973, most people still knew what it really was: a particularly heavy British bomb intended to destroy entire blocks of houses during World War II. The transfer to big cinema films corresponds to the same intellectual analogy to which our word bomb success owes its origin.

Ironically, the title of the exhibition does not come from the air war, although almost everyone thinks that today. Bomber weather is an urgent Nazi suspicion among laypeople. But as a synonym for thunderstorm and as an expression of particularly fine weather, it can be traced back to around 1900 - long before the first bomber appeared in the skies of Germany. At most, the originally positive word got a bitter connotation during World War II, because air raids were particularly common when the sky was bright. But in the language of Nazi propaganda the term was never used.

On the other hand, the word high-flyer, which is usually transferred completely impartially today, has a real origin in the air war. There are high-flyers in sports, in the hit parades and - documented in the exhibition - among Germany's cooks. But originally, a VTOL was an airplane that could take off and land vertically like a helicopter without a long runway. In the 1950s and 1960s, the military had high hopes for such technical developments. One of the best-known and most frequently used models is the Hawker Siddeley Harrier, which is still in service with many air forces around the world today.

The Munich exhibition can be read – among many other things – as an introduction to modern linguistic theory of meaning. The use of words like blockbuster, whiz, ejector seat and dud is often scandalized by vigilant amateurs - just like the many other expressions originally from the field of war, such as running the gauntlet (a cruel punishment in old armies) or overshooting (in artillery in the war a dangerous mistake).

The idea behind this is that it is morally objectionable to use expressions with such a spooky background metaphorically in harmless, often meant to be funny, contexts. Some even believe that such a "militarization" of language affects the speaker's consciousness in the sense of neuro-linguistic programming and that only when the language is completely pacified will eternal peace on earth approach.

But the meaning of a word, linguists agree, is not determined by what it meant a long time ago, but by how it is used in the language. With most of the words mentioned, nobody thinks of their old meaning anymore, often, as explained, it is even completely unknown. Anyone who describes a pop singer as a "high-flyer in the charts" or goes to the cinema to see a blockbuster is not in a military mood or even a mental war participant.

"Bomb weather. Air warfare and language” at the Schleissheim airfield. Until April 9th

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated)

What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated) Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation

Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application

Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application “I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing

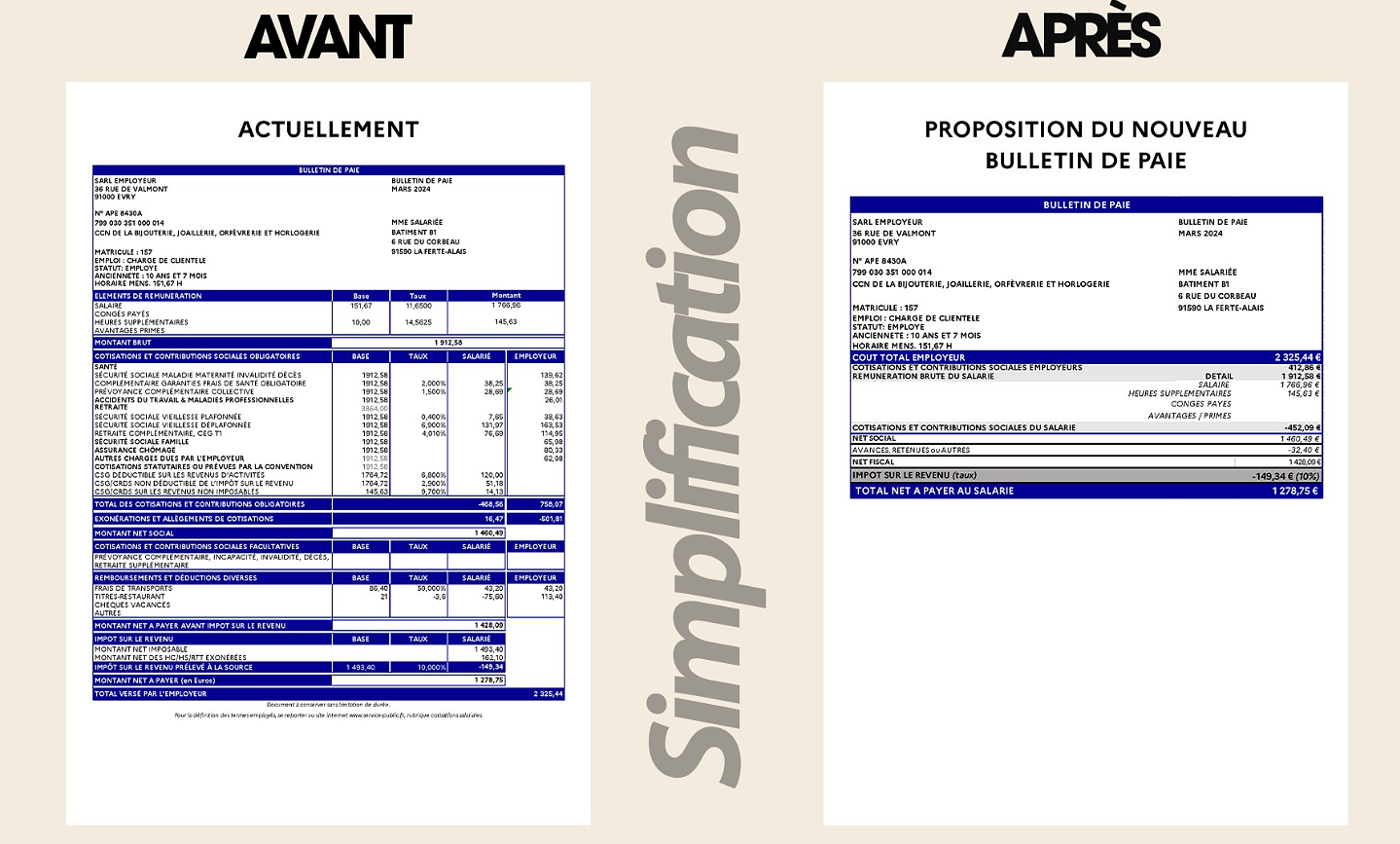

“I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy 25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits

25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan

At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga

Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker

Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops

OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet

Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid

Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid