A technically perfect assassination – there is no other way to describe what happened on Thursday, November 30, 1989 at exactly 8:34 a.m. on the Seedammweg in Bad Homburg. When the armored (officially: "specially protected") Mercedes type S-Class drove past a bicycle parked on the side of the road, the car broke through a light barrier that had been activated just seconds before.

Their impulse triggered a powerful detonation: about seven kilograms of TNT explosives exploded behind a copper plate and shredded the right rear door of the car. It was probably part of a window crank that hit the passenger sitting behind it and ruptured his femoral artery. Within a short time, Alfred Herrhausen, spokesman for the board of Deutsche Bank, bled to death in the wreck of his car.

"That would have overturned a tank," said a high-ranking intelligence officer shortly thereafter, only slightly exaggerating. Since there was simply no better protection than such "specially protected" limousines with two additional escort vehicles, it was clear that even the highest officials of the state could fall victim to a similar attack. Wolfgang Steinke, then head of department at the BKA, saw the assassination as a warning; the perpetrators wanted to prove: "If we want to, we can single out and kill anyone without exception."

Whether he was right or not remains to be seen, because the murder of Herrhausen (his driver Jakob Nix survived injured) was never tried in court. Even decades later, it is unclear who exactly the perpetrators were - but not from what background they came: BKA specialists already found a welded plastic film with a sheet of paper at the scene of the crime, on which a machine gun was printed in a five-pointed star and on which "Command Wolfgang Beer" was written. Forensic investigations confirmed what the investigators on the spot immediately suspected: the sheet actually came from the terrorist group Red Army Faction (RAF).

This was confirmed by a "letter of confession" that was received by several press agencies five days later. It said, in the typically inhuman language of left-wing extremists: "On November 30, 1989, we executed the head of Deutsche Bank, Alfred Herrhausen, with the 'Commando Wolfgang Beer'. We blew up his armored Mercedes with a self-made shaped charge mine.”

Despite numerous conspiracy theories, there is no reasonable doubt that the “third generation” of terrorists, who were deadly active from 1984 to 1993, were the perpetrators. The RAF terrorist Birgit Hogefeld, who was certainly involved in several murders of the "third generation", clearly judged all these speculations in the group's tacky jargon: "In the radical left-wing contexts that I know, this nonsense never had any meaning." But openly confessed in a conversation with the magazine "Der Spiegel" from prison because she "did not want any Herrhausen charges as a result of this conversation".

Like all terrorists, the RAF was never actually concerned with politics, much less with concrete progress. Their goal was and is only to shake societies as much as possible. The RAF relied on assassinations against people in whom they saw supposed "enemies of the people". They could be German police officers, Dutch or Swiss customs officials, representatives of the judiciary, diplomats or leading representatives of business. The “second generation” had already murdered a well-known banker in 1977, Jürgen Ponto – the head of Dresdner Bank at the time was rightly regarded as the central figure in the German economy. Twelve years later, the next terrorist “generation” killed yet another financial thought leader.

Born in 1930, Alfred Herrhausen came from a middle-class family. Achievement, especially personal achievement, was central to him. As a high school student during the Second World War, this almost inevitably led him to one of the more than 40 Nazi elite schools, specifically to Feldafing on Lake Starnberg. Nevertheless, Herrhausen was never a Nazi, on the contrary: he had learned his lesson as a youth.

After graduating from high school, Herrhausen studied economics in Cologne and passed his doctorate in 1955 at the age of 25. His understanding of achievement included the fact that he had previously worked parallel to his studies, namely as an assistant manager at what was then Ruhrgas AG, whose main business was the sale of town gas, i.e. a by-product of coal mining and its coking; Natural gas from mainly German gas fields accounted for only a small proportion at the time.

After graduating, he moved to the United Electricity Works Westphalia, a large municipal energy producer. Here Herrhausen made a career and in 1966, at the age of 36, became a member of the board. But only three years later, Herrhausen accepted the offer to move to the largest bank in Germany, Deutsche Bank, in the same position. Here he was initially responsible for parts of the international business and in 1985 he was promoted to one of the two spokespersons of the Management Board - Deutsche Bank repeatedly relied on dual leadership.

Certainly with flexibility. Therefore, after the age-related change of his colleague Friedrich Wilhelm Christians to the head of the supervisory board in May 1988, Herrhausen rose to become the sole spokesman of the board. Since then, he has been the best-known banker in Germany, who was perceived as an exceptional figure.

And at the same time always surprised. For example, in 1987/88 with the push to waive some of the debts that developing countries had accumulated. A few years later, the (perceived) breach of taboo became the means of international poverty reduction. Herrhausen also recognized early on that new methods of investment banking were gaining in importance. He therefore bought the London investment house Morgan Greenfell for Deutsche Bank just three days before his violent death. It is purely speculative whether the wrong developments were inherent in this decision, which, under Herrhausen's third successor, Josef Ackermann, led the bank to the brink of crime (and sometimes, at least too often, to the point of crime).

In any case, the murder of Herrhausen weakened Germany. An independent mind like him could undoubtedly have given many important impetus in the year leading up to the unification of the two German states. The same applies to the last casualty of the RAF madness, the head of the Treuhand Detlev Karsten Rohwedder, who was shot in 1991.

You can also find "World History" on Facebook. We are happy about a like.

"Assassin", the first season of "WELT History" - subscribe now to Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Deezer, Amazon Music, Google Podcasts or the RSS feed directly.

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

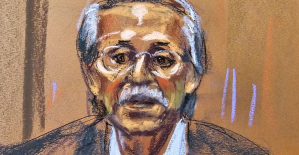

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation

Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application

Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application “I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing

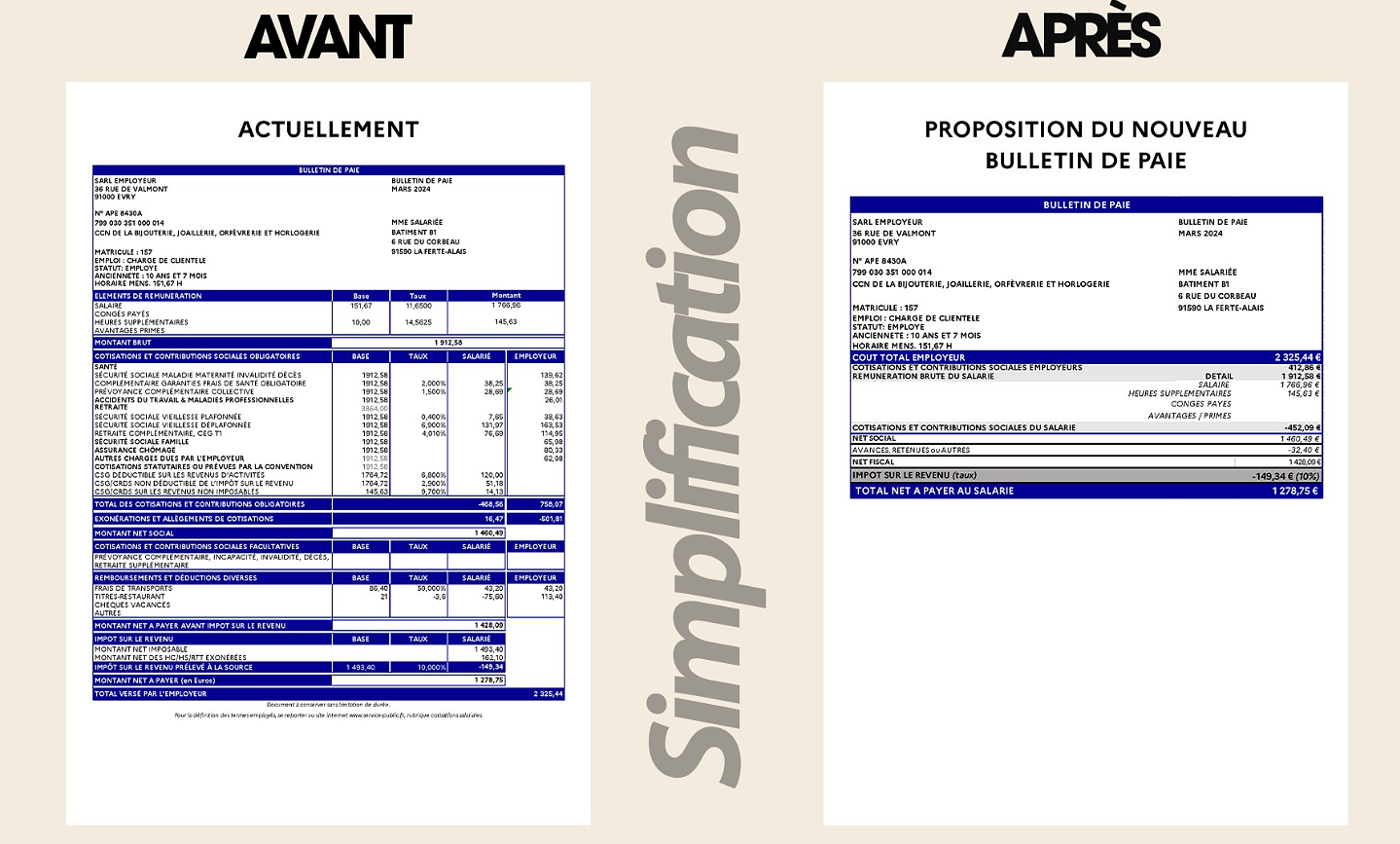

“I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy 25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits

25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan

At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga

Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker

Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops

OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet

Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid

Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid