Until recently, they covered the distance on foot. A road connected their tiny village to the world, a lifeline for this ancestral community of fishermen and artisans living on the shores of the largest desert lake in the world.

But three years ago, the emerald waters began lapping at the circular huts, then rising, reaching levels never seen in living memory.

The area of Lake Turkana, considered one of the cradles of mankind, extends over 250 km long and 60 wide in northern Kenya. However, it increased by 10% between 2010 and 2020, according to a government study published last year, and nearly 800 km2 of land have been swallowed up.

Several factors explain this phenomenon: extreme precipitation on the watersheds, linked to global warming, increased runoff from the soil linked to deforestation and agriculture, but also tectonic movements.

The El-Molo saw their only freshwater pipeline disappear, as did the burial mounds of their ancestors. The waters even ended up closing in on the road, isolating the inhabitants on an island in the middle of the lake.

"Before, there was never any water here. You could drive a jeep through it," says Julius Akolong, as he crosses the wide channel that now separates his community from the rest of northern Kenya.

Trapped by the waters of the lake, sometimes called the "jade sea", the El-Molo community found itself deeply affected, as its unique heritage was already under threat.

- "Those who eat fish" -

They were barely 1,100 according to the last census of 2019, a drop of water among the 50 million inhabitants and more than 40 ethnic groups in the country.

Known as "those who eat fish" by the herding tribes of northern Kenya, the El-Molo are said to have migrated around a millennium BC from Ethiopia to Turkana.

Today, few speak their ancestral language. Over generations and marriages with neighboring tribes, customs have evolved or disappeared. The unexpected rise of the lake fragmented the rest.

Some of the displaced have made the heartbreaking decision to erect a makeshift camp on the opposite shore: shacks set in a barren, windswept glade. The school is certainly closer, but the world of their community more distant.

"It was very difficult. (...) We had to discuss it with the elders so that they gave us their permission or their blessing to leave without curses", says Akolong, 39 years old and father of two children.

For those who stayed, life on the island turned into a battle.

Fishing nets and baskets used for millennia, hand-woven with reeds and palm fibers, have become less effective in deeper waters, smaller catches.

No longer able to access fresh water, the El-Molo were forced to drink water from the Turkana, the saltiest lake in Africa. The ailments - dental, capillary - followed.

"We often have diarrhea (...) we have no other drinking water. That's all we have. It's salty and damages our teeth and hair," says Anjela Lenapir, 31, mother of three children.

- Indelible damage -

Children were otherwise penalized. Most of them are stuck at home, deprived of school because their parents cannot pay for transport on the fishing boat, deplores David Lesas, deputy director of the primary school in El-Molo Bay.

The local government and the NGO World Vision are helping, but resources are scarce and needs are many in this severe drought-stricken region.

The school fence and the toilet block are under water, crocodiles have invaded part of the playground.

But the real damage to El-Molo is indelible.

Separated from its people, Akolong has missed the initiation rites, baptism ceremonies and funerals that reinforce tribal identity and community.

"We are now divided," he blurts bitterly.

The cairns materializing the tombs of the ancients have been swept away, and with them the memories of the past. The lake also threatens the revered shrines of tribal deities.

“It is a place that is deeply respected in our culture,” Lenapir points out: “With the rising waters, we will also lose this tradition.”

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation

Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application

Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application “I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing

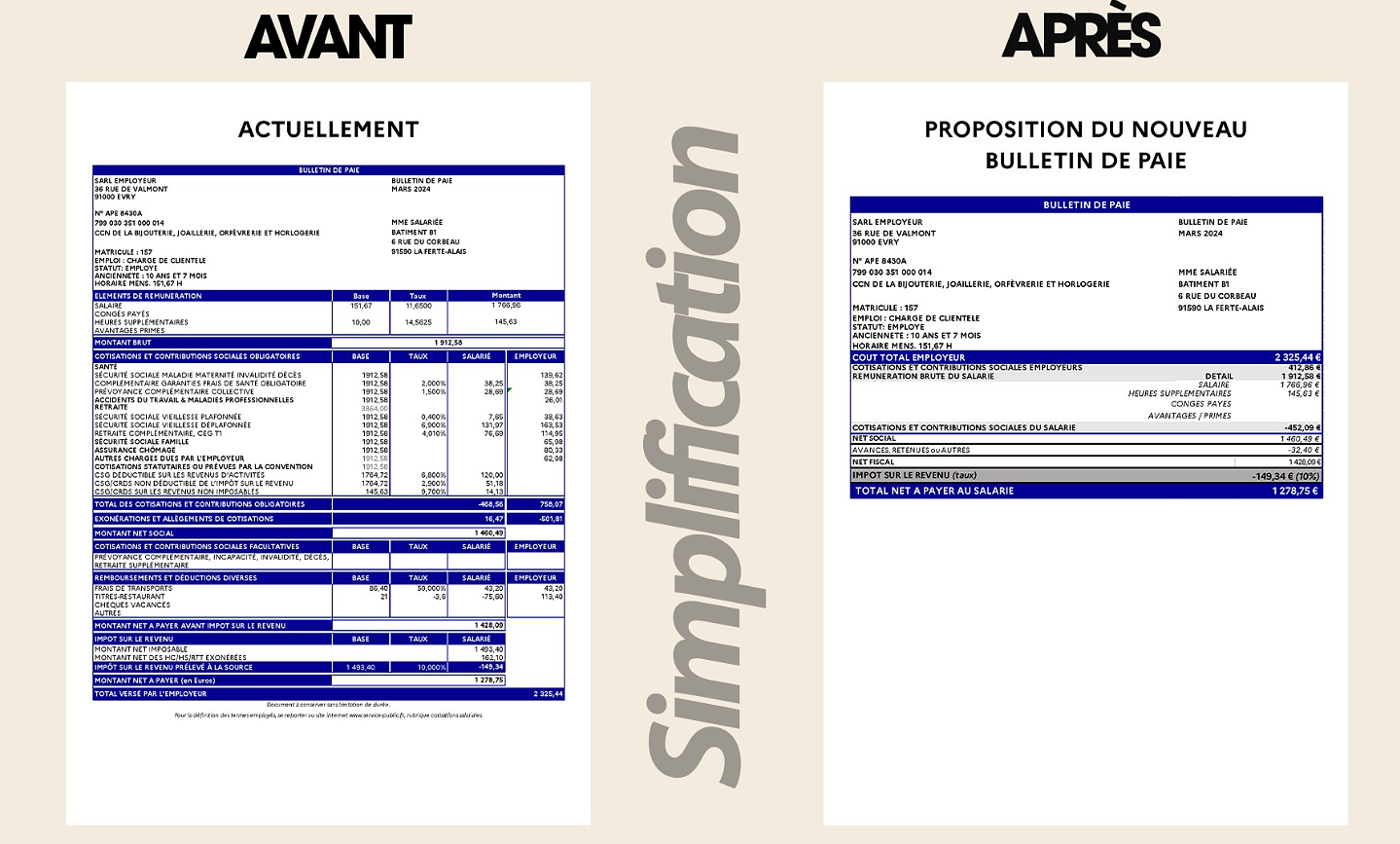

“I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy 25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits

25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan

At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga

Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker

Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops

OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet

Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid

Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid