On Christmas Eve last year, Minister of State for Culture Claudia Roth (Greens) put a happy message under the tree: “In order to build up immunity to some extent”, the inclusion of culture as a state goal in the Basic Law is now an immediate task. The choice of words reflects the survived pandemic, which has the effect of a cultural “long covid” in the country’s institutional cultural life.

The demand to anchor culture in the Basic Law is not new. Rather, it seems as if it is washed up to the surface again and again at certain intervals, only to – at least up to now – disappear again after a short debate. As early as the beginning of the 1990s, a “Joint Constitutional Commission” had advocated the inclusion of this state objective in the Basic Law.

In 2006, the commission of inquiry “Culture in Germany” proposed anchoring the sentence “The state protects and promotes culture” in the constitution. A corresponding draft law came from the FDP at the time, but it had no consequences. Six years later, the SPD made a good start and also looked at sport: “It [the state] also protects and promotes culture and sport.” Even that was not enough to change the constitution. Now Ms. Roth is trying again to persuade the legislature to have higher insights.

In the current constitution, art is addressed centrally in one place. Art. 5 (3) stipulates that “art and science, research and teaching” are free. This is a defensive right. In Art. 5 (3), the Constitutional Court also sees a fundamental decision for a state goal of "cultural state", but emphasizes that no concrete funding scenarios can be derived from this.

There is not much more to be found. Art. 73 and 74 stipulate that individual areas of law such as copyright and foreign cultural policy are in the hands of the federal government. Otherwise, if there are no more detailed provisions, it can be concluded that the federal states have their own creative field in cultural policy. The proposals to expand the Basic Law to include a cultural-political article all refer to two central terms: “art” and “culture”. Entire libraries have been written about how to fill these terms with content.

Three levels of meaning can be distinguished for the term culture. The first concerns the difference between culture and nature, which is the closest to the Latin word root "cultura", which means agriculture. Today, this meaning plays a central role, above all in the ecological discussion, which is much too broad for cultural policy.

A second layer of meaning concerns differences between groups of people, this is no longer about culture, but about cultures. A culture in this sense describes how a group of people acts, which can range from banal differences (eating with a spoon or chopsticks) to greeting rituals (two or three little kisses on the cheek) to fundamental, often religious values. When a “leading culture” is demanded in Germany in the political arena, this concept of culture is addressed. One value system and framework for action should then be placed higher than others.

The idea of a “dominant culture” also makes clear the potential for political conflict that is inherent in the concept of “cultures”. The idea implicit in the “leading culture” that such “cultures” can be sharply demarcated scratches hard on the worldview of the identitarian movement, it misses the reality of life in an interdependent world. In any case, the favoring of a "dominant culture" through state action, where it extends to artistic expressions, contradicts the right of defense in Article 5 (3) of the Basic Law.

In a third layer of meaning, culture is simply understood as what generally represents the field of action of cultural policy: culture is then best understood as the system of cultural sectors, i.e. music, performing arts, fine arts, literature, perhaps now also “socioculture” and many more. Although this is not conceptually sharp, it has been introduced as a field of political practice. A cultural policy understood in this way neither reaches the dimension of the fundamental relationship between "culture and nature" nor "the cultures", but refers to the cultural sector, i.e. the theatres, town halls, publishers and bookstores, socio-cultural centers and clubs.

The question of what art is is perhaps even more difficult to answer. Karl Valentin was perhaps not wrong when he pointed out that art comes from ability. The demarcation of art from craft has only emerged in modern times. It was not until the 19th century that the idea emerged that “high art” had to be distinguished from trivial, but possibly entertaining and therefore more joyful art, and it was only then that the temples of art and culture emerged, which today determine the institutional cultural scene. Such “high art” goes hand in hand with notions of appropriate behavior, with cough-free, adoring silence in concerts, with silent pausing in front of the work in the art museum.

Social practice in dealing with art is different. A rough distinction can be made between those cultural practices that are part of the life of majorities and those that are the subject of state support. The dense landscape of theaters and orchestras, usually with permanent ensembles, as well as museums and monuments, account for by far the largest part of public spending in this sector. In public funding practice, above all, the offers that the state sees as merit goods, whose presence in the market should be ensured, are taken into account.

A fraction of public funding then goes to so-called free culture. Such support is usually project-related, rarely also institutional. The socioculture that is so important in urban and rural areas has a place here. But 80 to 90 percent of the art produced, distributed and consumed is, in a conservative estimate, offered and realized privately on a consumer market.

Addressing this circumstance reflexively evokes accusations of “neoliberalism” in the cultural-political debate. However, the situation can also be formulated differently: Participation in the state-sponsored cultural wealth of society only reaches 10 to 20 percent of the population. Most people are marginalized because their cultural needs are ignored when cultural policy funds are distributed.

The major funded structures in the art world have not only been in crisis since the Covid pandemic. A decline in audience, which has been announced for a long time, was amplified in the pandemic. It has to do with shifts in the social structure, with an erosion of the classic bourgeoisie. The old audience will not return. The big institutions, especially in the theater and concert business, will have to change - or they will lose their right to exist.

However, the idea of “high art” is still being adhered to, which should be far removed from any commerce, even if it ties up considerable public budgets. Such an understanding of art continues to shape the funding process. This only works because there are self-appointed and stately door guards who determine what is art and what is not. These door guards often act in their own interest, to protect their own facility, which offers them a playing field and ensures their economic well-being. Art understood in this way is part of domination, of the domination of interpretation. The fact that a majority of the population is hardly interested in this art scene has no meaning behind such interests.

Against this background, when emphatically “Culture in the Basic Law” is demanded, the consumption of art and the artistic production of majorities are not meant at all. Rather, it is a matter of establishing the preservation of existing structures and content as a state goal. The demand for art and culture to be laid down in the Basic Law as a positive state goal tends to be about making existing structures museums, not about taking changes in society and in art and culture into account in funding practice. That can also mean radical institutional change.

If the goal of state cultural policy is to support the democratic structures in this country with cultural funding, then this must start with the funding practice, but not with the constitution. In addition, every conceivable wording for a culture article in the constitution undermines both the complexities of the terms art and culture and federal responsibilities. The Christmas promise of the Minister of State for Culture would at best be one to preserve structures. Reviewing them critically over and over again is a far more rewarding task.

Dieter Haselbach is Director of the Center for Cultural Research in Berlin, Peter Matzke is Managing Director of the Krystallpalast Varieté in Leipzig.

Sydney: Assyrian bishop stabbed, conservative TikToker outspoken on Islam

Sydney: Assyrian bishop stabbed, conservative TikToker outspoken on Islam Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases”

Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases” Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK

Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years

In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years WHO concerned about spread of H5N1 avian flu to new species, including humans

WHO concerned about spread of H5N1 avian flu to new species, including humans New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria

New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting

Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence

The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence Bitcoin halving: what will the planned reduction in emissions from the queen of cryptos change?

Bitcoin halving: what will the planned reduction in emissions from the queen of cryptos change? The Flink home shopping delivery platform will be liquidated in France

The Flink home shopping delivery platform will be liquidated in France Bercy threatens to veto the sale of Biogaran (Servier) to an Indian industrialist

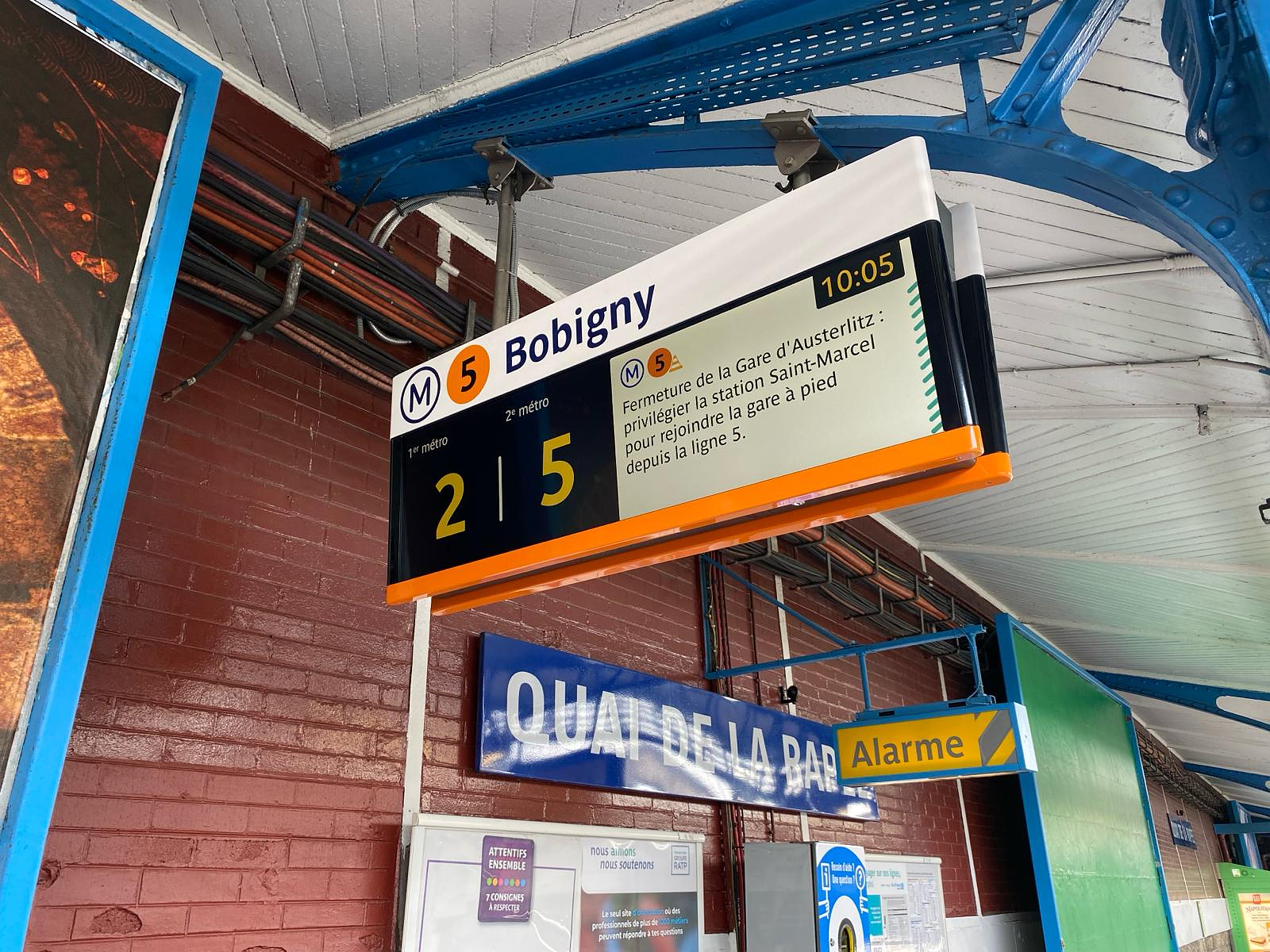

Bercy threatens to veto the sale of Biogaran (Servier) to an Indian industrialist Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF?

Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF? The main facade of the old Copenhagen Stock Exchange collapsed, two days after the fire started

The main facade of the old Copenhagen Stock Exchange collapsed, two days after the fire started Alain Delon decorated by Ukraine for his support in the conflict against Russia

Alain Delon decorated by Ukraine for his support in the conflict against Russia Who’s Who launches the first edition of its literary prize

Who’s Who launches the first edition of its literary prize Sylvain Amic appointed to the Musée d’Orsay to replace Christophe Leribault

Sylvain Amic appointed to the Musée d’Orsay to replace Christophe Leribault Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie

During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Tour of the Alps: Simon Carr takes on the 4th stage of the Tour of the Alps, marked by a big scare

Tour of the Alps: Simon Carr takes on the 4th stage of the Tour of the Alps, marked by a big scare Cycling: in video, Chris Harper's big scare on the 4th stage of the Tour des Alpes

Cycling: in video, Chris Harper's big scare on the 4th stage of the Tour des Alpes Football: Mathieu Coutadeur will retire at the end of the season

Football: Mathieu Coutadeur will retire at the end of the season Athletics: young Tebogo says African sprinters will dominate the season

Athletics: young Tebogo says African sprinters will dominate the season