One of the best-known districts of Copenhagen is Christiania, an autonomous colony that has been tolerated by the state since 1971. Hippies have occupied a former military barracks, there are yoga and meditation rooms, but no leases to this day. The residents pay taxes and fees for utilities, everything else they take care of themselves. Cannabis is sold publicly, which leads to gang wars. Police raids are the order of the day. The songwriter Lukas Graham, 34, son of a Danish father and an Irish father, was born and raised in Christiania. He calls his music "ghetto pop", a mixture of soul, funk, hip-hop and pop. His fourth album has just been released.

WORLD: When you sing, you sound so soft and fragile. But you once said that your life in Christiania made you strict and hard. How does that fit together?

Lukas Graham: In Christiania we grew up with a lot of police raids because there was a market with criminals around the corner. I also developed a certain hardness because I had to bury loved ones. I've really lost many, my father for example, a friend who committed suicide, or others who died from an overdose or from gang violence. It all gives you a certain severity. In this way I can express my feelings and the states of mind that I have been through.

WORLD: As a child, were you treated differently at school because you came from Christiania? Were you some kind of black sheep there?

Graham: Oh yes, definitely. The teachers were just mean. They just expected something very specific from a child from this area and treated me accordingly. I remember one time in physics class: I dropped a calculator on the floor, it broke, and the teacher yelled at me that he couldn't just go and steal a new calculator somewhere, as is customary in Christiania. It was nonsense, of course, and it just hurt me. I do think I got in more trouble than I deserved, but in the end it only made me stronger.

WORLD: In Denmark they call you the "Angel of the Ghetto" - would you see yourself as a ghetto child?

Graham: Yes, definitely! The only difference between me and the guys I grew up with is that the police never caught me. I've also sold weed and been involved in riots. The difference is that I found a way out of it thanks to the music, I didn't get stuck in it.

WORLD: When did you smoke marijuana for the first time?

Graham: I think I was about twelve.

WORLD: Was that normal for twelve-year-olds in Christiania?

Graham: I don't know if it was normal. We really started around the age of 15, 18 and I stopped when I was 31.

WORLD: How do you see it today?

Graham: I think we should talk a lot more with children and young people in general, and certainly adults, about how to be social without using drugs. I think most problems start with the drug culture or with alcohol because it's available everywhere. If alcohol were invented today, it would definitely be illegal, c'mon! (laughs)

WORLD: You once said that the children in Christiania live in fear - they just don't know it until they grow up. When did you first become aware of this fear?

Graham: It has to be said that it's not a constant fear. But normal kids grow up thinking that the police are someone to protect them, right?

WORLD: Definitely. don't you?

Graham: I grew up thinking, if you see police, turn around and go somewhere else because something bad is likely to happen. The police behaved badly and still do in Christiania. That's a real abuse of power, the way they're behaving in my neighborhood. I think I was in my teens or twenties when I realized I would never ask a cop for directions. Or if something bad happened to me, my first instinct wouldn't be to call the police either. From my experience, she would not help me, but only make things worse. I think all ghetto kids, all kids growing up in marginalized neighborhoods, have this deep fear that something bad is going to happen.

WORLD: Has this feeling towards the police not changed with age?

Graham: The problem with something that started in your childhood is that it's very difficult to process rationally. You can move away from the place where it all happened. You can also try all sorts of mental exercises and therapies, but it stays in the body. It's your body that remembers how it feels when it's beaten up by the police. And it's also your body that knows how it feels to be arrested by the police when you haven't done anything. I think I was ten years old when the police first asked me to empty my school bag and take off my winter jacket so they could search me. Without any reason. That kind of abuse stays with you, you can't run away from it.

WORLD: In your music you manage to convince with words. Why didn't you try it with words in Christiania as well?

Graham: Well, as a 16-year-old I didn't exactly have a platform for it at the time...(laughs)

WORLD: But you got older and your words more and more beautiful.

Graham: And now I have a corresponding platform.

WORLD: Did your parents never try to stop you from violence?

Graham: My parents didn't think it was a good idea to take part in the riots, but young people are willing to do revolutionary things or become activists, while the older ones tend towards the center and are becoming more and more conservative.

WORLD: You too are getting older. So are you also becoming more conservative?

Graham: I think taxes are a positive thing so the rich can help the poor and so we're able to keep crime down. I wouldn't call myself a Marxist right away, but I do rank far left in my views on how we should tax corporations and the really rich. I pay a lot of taxes myself, and I'm happy to pay them, whether they're my company taxes or my personal taxes. Because I think it's a pretty good system.

WORLD: But that sounds like a good step towards reconciliation with society.

Graham: I actually think the state isn't doing such a bad job. In Denmark we have a fairly high level of transparency and a very low level of corruption – which is not to say that there is no corruption. Our school system is not bad either, we have a pretty good public transport system. You see, most things work in a country like Denmark. It's certainly similar in Germany. But that doesn't mean that we can't do even better.

WORLD: Is Christiania still a very special place of freedom for you?

Graham: Yes, there is definitely a very high level of personal freedom there. Drug sales have changed over the years. Unfortunately, the more government and police control the market, the tougher it gets. But my mother still lives there, as do many of my childhood friends. I returned there for Christmas, to the “Grå Hal”, the gray hall. Something is happening there that we call 'Christmas for the Christmas Lost'. Thousands of people come who don't know where to spend Christmas. You get free food there. I like this place for its ability to help those who really need help. We are setting an example that we are stronger together. I find that the modern world is becoming more and more selfish and egotistical, and we humans tend to forget that sharing is caring.

WORLD: So you learned to share in Christiania?

Graham: In my opinion, living a totally selfish life doesn't really make you happy. True happiness comes from the ability to uplift and support other people. If we're going out to eat at a nice restaurant and we know someone who can't afford it, should we send them home first? Or shouldn't I or someone else pay for it? I find it very important to really share and find a more communal way of looking at how life should be lived. I think that makes you really happy.

WORLD: You say your mother still lives in Christiania – did she never want to move away from there?

Graham: She still lives in the house I was born in. And it's always nice to go back and visit them.

WORLD: Why did you actually want to study law, after everything you said. Was that something like going to bed with the enemy?

Graham: It was more about really getting to know the system in order to be able to win battles against the system. In case I didn't become a musician. I stopped studying law when I signed my record deals.

WORLD: You were enormously successful in 2015 with the blue album and the hit "7 Years". What has happened in between?

Graham: I had two fantastic daughters, which of course was the most important event. And as a result, my life has changed significantly. I think it's great that I'm no longer the most important person in my life, there are now two girls who are much more important. I find that it has calmed me down, I'm not in such a hurry anymore. I can enjoy life more.

WORLD: You don't look like you're in a hurry either (Lukas conducts the video call while lying down).

Graham: That's right, I'm definitely not in a hurry. I'm lying in a huge hammock, like in a gigantic spider's web. (He moves the camera so you can see the room. It looks like a gigantic climbing paradise). I think it's nice to be in my thirties now. I have a little more self-confidence and am more relaxed. I challenge myself to make life a little harder, and that's a great way to live.

WORLD: Is the responsibility of being a father of two a good feeling?

Graham: Yes, it's wonderful to come home and have breakfast together the next morning. I love spending time with my kids, it's a beautiful feeling. But I also had such wonderful parents myself that it was clear to me that I wanted a family - I have them now and that's great.

WORLD: Were your daughters born in the hospital or like you on the living room sofa?

Graham: The older one was born at home like me and the younger one was born in a special part of a hospital that doesn't use drugs and stuff like that. In a kind of big bathtub. That was really unique.

WORLD: The cover of your albums always shows the same picture. The original hangs in your favorite pub in Copenhagen. They simply changed the color overlaid on the image. Does it have a special meaning for you?

Graham: I think there's a special connection to this little restaurant, Café Wilder, where we used to go to eat with the whole family when I was growing up. I still visit it today with my own children. On the wall is this amazing painting that does a pretty good job of depicting my writing of song lyrics. It's very naked, very honest. I think it's a really beautiful painting. That's clever with the colors, isn't it? So I don't have to think long about a new album cover. The new one is pink. Looking at the four albums side by side it looks really cool to have the same cover in different colors. I think that's going to be really iconic.

WORLD: Is the new album a big introspection?

Graham: Yes it is. I like to write my songs as an introspective, as a sort of throwback to what happened in my life, as a songwriting process. I also enjoy writing concept songs like "Home Movies" - but it's something special when you write autobiographically. I think it's really nice to be able to be so honest about songwriting. Do you know what I mean? If you never lie, you don't have to remember what to say, you just keep talking.

WORLD: What is your favorite song on the new album?

Graham: The last song, "One by one" is one of my personal favourites. When I hear this song in the right environment, it really touches me. It's about the fact that everyone has to die one day, but also that one day my children will move out and it will break my heart when their rooms are empty. I can still vividly remember the day I wrote this song with two good friends, James Matthew and David LaBrel. We were just three grown men sitting together and talking very sentimentally about our experiences with children. David and I both have kids, and I remember when James was writing the song he was like, 'Oh my god, that's how my mom feels.' And yeah, it's a really, really special song for me, this " one-by-one".

WORLD: It is said that you were strongly influenced by rap. Have you also adopted the rage of rap for your music?

Graham: I wouldn't necessarily call it anger. I think it's more accurate to call it structural violence and that this angrier sound with minorities in America and England is more systemic, it's not originally coming from the rappers themselves. I think that we - especially here in Europe – usually don't think about the fact that this structural violence exists, not only against minorities, but also against women, for example. I just grew up in an area where there was such structural violence. The government constantly threatened us with expulsion and sent violent police officers. Something like that causes a certain uneasiness in children and young people. So I don't necessarily think I got that anger just from rap, it was there before because of the way the police treated us. Rap just expressed what we were already thinking.

Lukas Graham, 34, was born Lukas Forchhammer in the autonomous Copenhagen district of Christiania. He started acting in Danish TV series at the age of five, has two daughters and lives in Copenhagen. Lukas Graham is a big star in Denmark, with every album topping the charts. In 2015 he celebrated a world hit with the song "7 Years", which sold more than ten million copies. He just released his fourth album. In March he will be on tour in Germany.

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

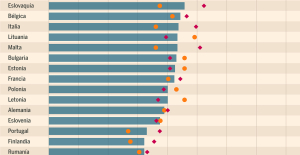

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation

Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application

Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application “I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing

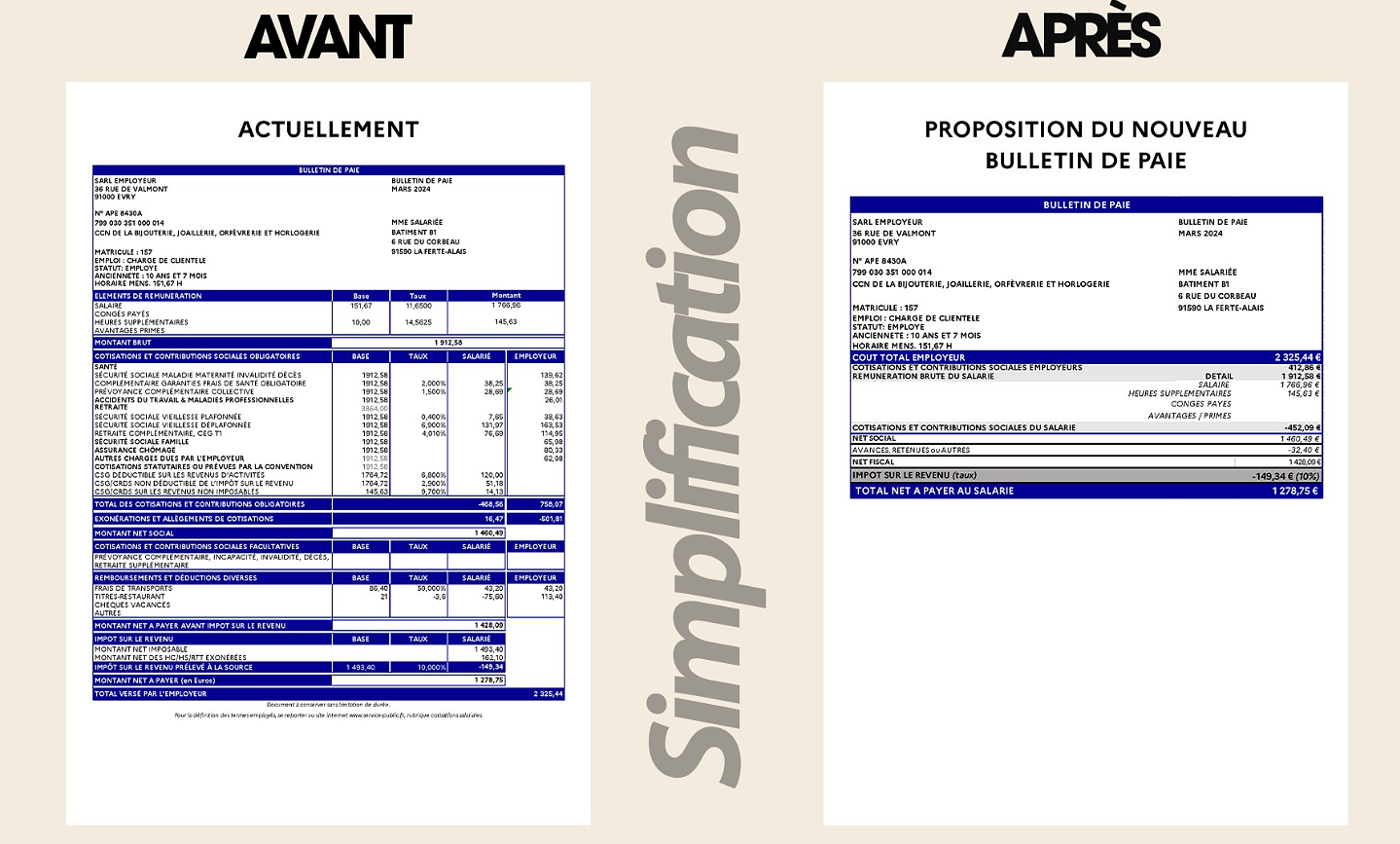

“I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy 25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits

25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan

At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga

Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker

Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops

OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet

Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid

Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid