The death of twelve-year-old Luise from Freudenberg in North Rhine-Westphalia caused horror. That a child becomes the victim of a crime is dramatic enough. But the fact that two girls of the same age have confessed to the crime leaves you speechless.

From the point of view of criminal law, the age of the two girls is of considerable importance. Because under German law, children under the age of fourteen are considered incapable of being at fault, according to Article 19 of the Criminal Code. So neither the seriousness of the crime nor the child's actual degree of maturity is taken into account: anyone under the age of fourteen must not be prosecuted.

For Luise's parents, this would mean that the crime against their daughter could not be prosecuted. This result can hardly be reconciled with most people's sense of justice. Even if serious criminal offenses by children are fortunately extremely rare: the call for a lowering of the criminal responsibility limit will – again – be loud.

The debate about criminal responsibility is very emotional here, which is understandable in view of the dramatic crimes involved. But it is of little use to call for unconditional toughness by the state without taking into account the special features of child development. It is just as exaggerated to paint the horrifying picture of "children in prison" and to reject any discussion of the culpability of children.

The main reason why our law does not punish children is that young people up to a certain age are not yet able to really understand the consequences of criminal activity. Even if they have a keen sense of right and wrong, they often fail to see the impact of their act on the victim or society.

But does that really apply to 12 or 13 year olds? It is not a question that lawyers can answer, but psychologists. Forensic psychologist Alexander Schmidt once told the Süddeutsche Zeitung: “The age limit is completely arbitrary in the sense that it is set normatively and cannot be derived from findings from developmental psychology. There is not much of a difference between a 12-year-old and a 14-year-old purely in terms of developmental stage.”

In fact, it seems unrealistic to assume that a child of 12 or 13 does not know that serious crimes such as murder or rape are wrong. These deeds are no longer childlike. The same applies to frequent offenders, who repeatedly receive feedback on their crimes from the police and youth welfare offices. These children, of course, know full well that their behavior is wrong.

The age limit of 14 years is therefore not scientifically mandatory, but a legal and political determination of the legislature - which can also turn out differently. A look at European countries such as the Netherlands or France, where children are criminally responsible at the age of twelve, shows this. in Switzerland or England, a procedure can even be carried out against ten-year-olds.

German law currently does not provide any adequate solutions. The state can hardly react to a crime as serious as that in Freudenberg. There are no options for sanctions, measures can only be taken to protect the perpetrators or to avert danger.

In many cases, the authorities are dependent on the cooperation of the parents, after all it is about support and not about coercion. If they refuse, there is often not much the state can do - unless there is a threat to the child's well-being.

This result is difficult to bear not only for the victims' relatives and society. It is ultimately not in the interest of the responsible children. Kant already said that punishment is also something that is owed to the offender. If there is no reaction to his criminal behavior, he is not taken seriously.

In the sensitive development phase of a child, it can be a fatal signal if no one reacts to his behavior. What do children learn when their criminal behavior remains without consequence? Crime can also be a call for attention - ignore it and make it worse. The waiver of any sanction is only superficially humane or liberal. Indifference can be just as damaging as excessive severity.

Serious crime is a clear sign that there are fundamental problems in the child's development. Intervention may therefore also be necessary to prevent future crimes.

In the spring of 2021, a fourteen-year-old killed a thirteen-year-old out of jealousy in Sinsheim, Baden-Württemberg. A few months earlier, the same perpetrator had severely injured a classmate with a knife, but the act had no consequences – the perpetrator was only thirteen at the time. Perhaps intervention after the first act could have prevented the murder in Sinsheim - and with it a tragedy for the victim, his family and also for the perpetrator himself; one day he will have to live with having caused unimaginable suffering to other people.

So what to do? The state must also give young offenders a clear answer to serious crimes. This is in the interest of the victim, but ultimately also in the interest of the children themselves.

But: A blanket lowering of the age of criminal responsibility cannot be the right way. Certain rule violations are part of growing up. Children try things out and test their limits. Criminological research shows that very few children and young people continue to commit crimes later in life.

Criminal behavior is therefore usually just a phase that will come to an end of its own accord as it matures. In most cases, therefore, criminal law is not required. It might even have the opposite effect on children. A criminal conviction can stigmatize young people and pigeonhole them early in their development: delinquents.

In detention there is also the danger that they will come into contact with older criminals and orient themselves towards them. And that in a particularly sensitive phase of life in which people are easily influenced.

State criminal proceedings therefore make little sense in the case of minor offences. For the thirteen-year-old shoplifter, talking to her parents will usually be sufficient. In the case of serious crimes, however, the situation is different. If you want to lower the age of criminal responsibility, criminal proceedings against twelve or thirteen-year-olds should be limited to particularly serious crimes or to intensive offenders.

And of course it's not enough to put 12-year-olds in jail. But that's not the way our juvenile criminal law is going either. Juvenile criminal law is aimed at education, there is not only imprisonment, but a wide range of sanctions. Children can be taken out of their environment and housed in assisted living groups, for example, in order to work with them therapeutically.

The author: Prof. Dr. Elisa Hoven is a judge at the Constitutional Court of the Free State of Saxony. At the University of Leipzig she holds the chair for German and foreign criminal law, criminal procedure law, commercial and media criminal law. New in the trade is the book: "Criminal Matters" by Elisa Hoven and Thomas Weigend (DuMont, 280 p., 23 euros).

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

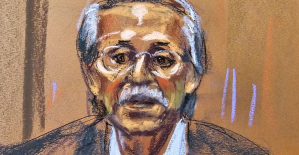

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? The shadow of Chinese espionage hangs over Westminster

The shadow of Chinese espionage hangs over Westminster Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated)

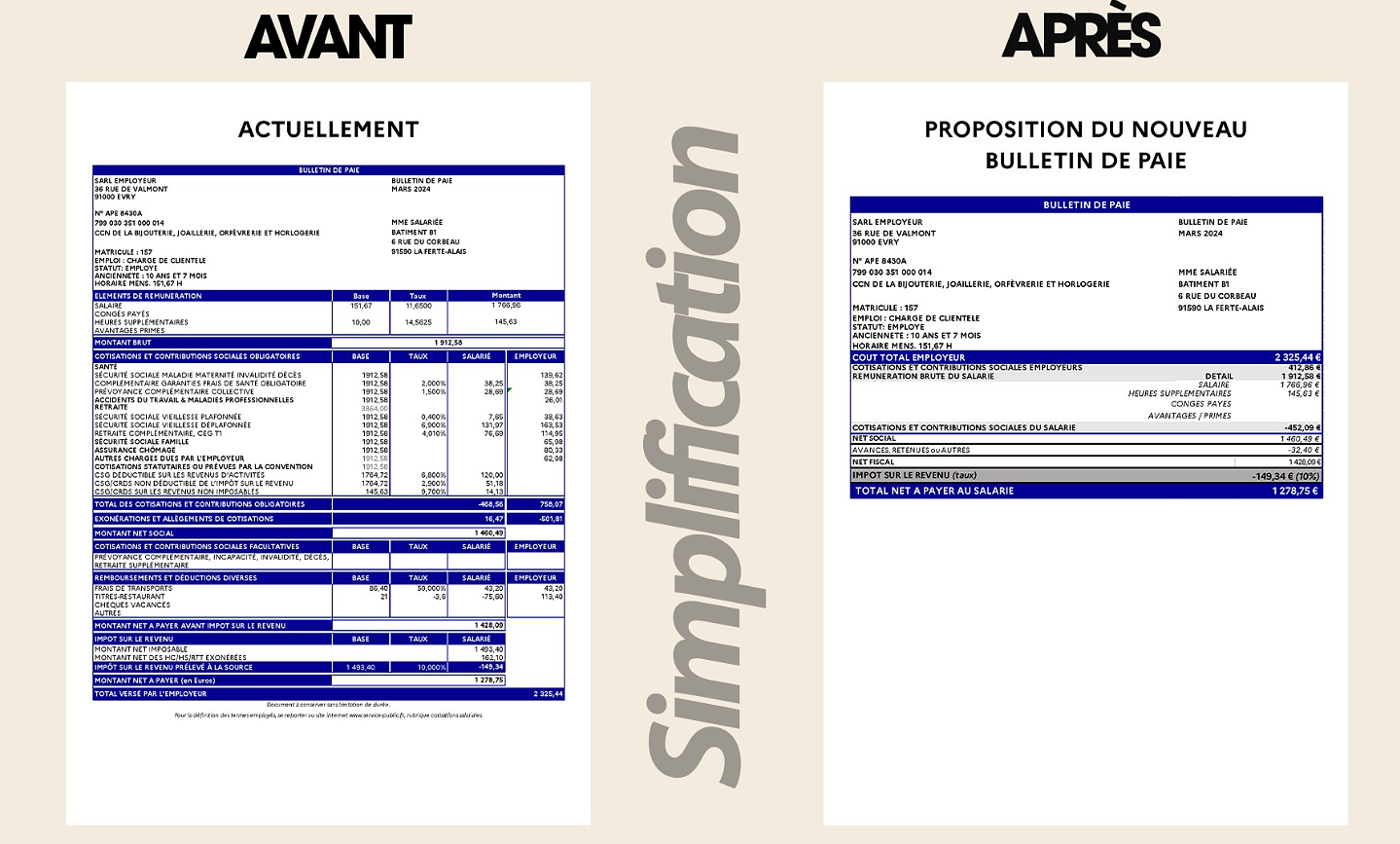

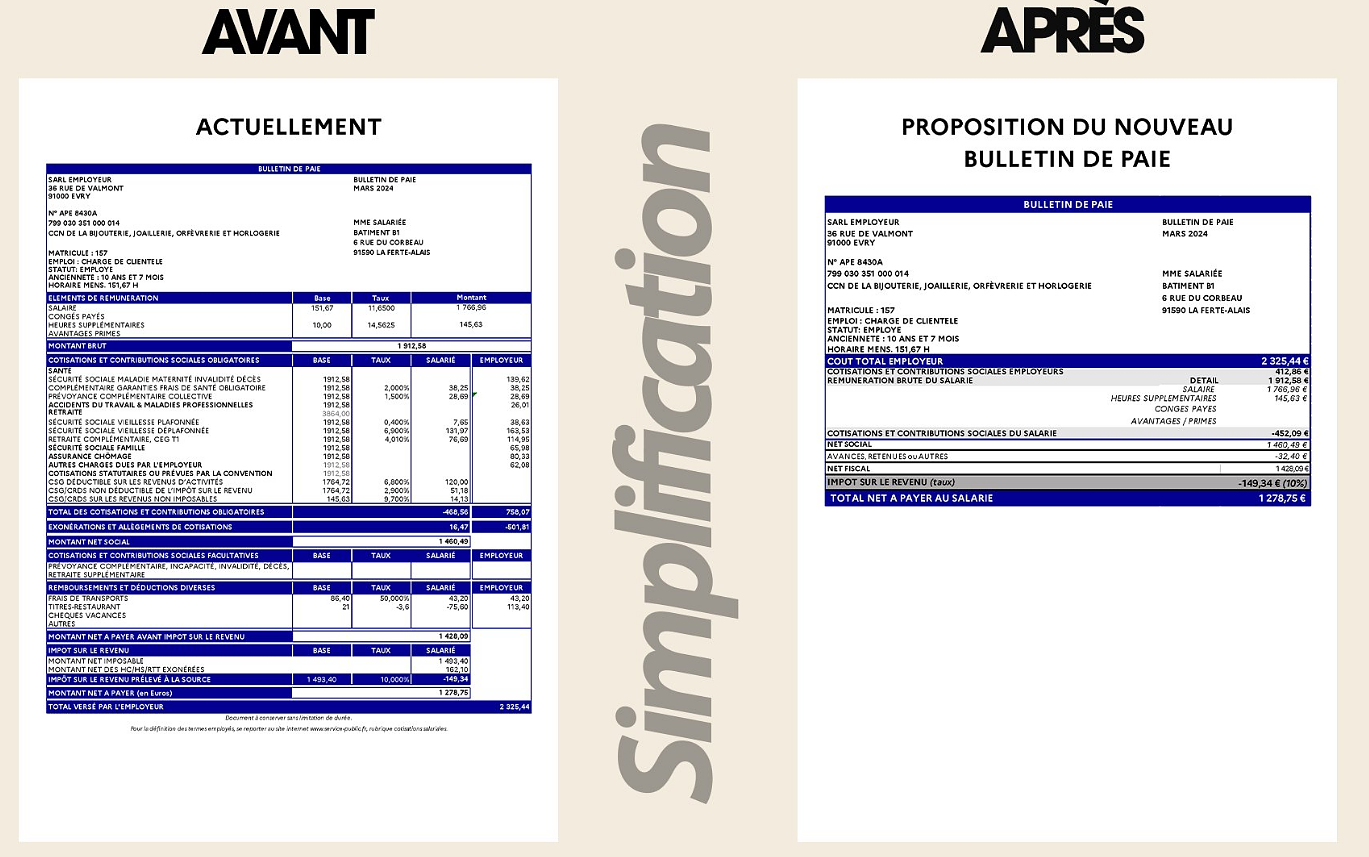

What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated) “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy Despite the lifting of the controllers' strike, massive flight cancellations planned for Thursday, April 25

Despite the lifting of the controllers' strike, massive flight cancellations planned for Thursday, April 25 The right deplores a “dismal agreement” on the end of careers at the SNCF

The right deplores a “dismal agreement” on the end of careers at the SNCF The United States pushes TikTok towards the exit

The United States pushes TikTok towards the exit Saturday is independent bookstore celebration

Saturday is independent bookstore celebration In Paris as in Marseille, the Flames ceremony opens to fans of rap and hip-hop

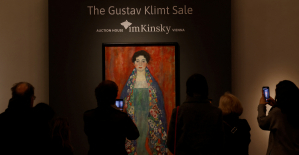

In Paris as in Marseille, the Flames ceremony opens to fans of rap and hip-hop Sale of the century for a mysterious painting by Klimt, in Austria

Sale of the century for a mysterious painting by Klimt, in Austria Philippe Laudenbach, actor with more than a hundred supporting roles, died at 88

Philippe Laudenbach, actor with more than a hundred supporting roles, died at 88 Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Montpellier-Nantes: at what time and on which channel to watch the Ligue 1 match?

Montpellier-Nantes: at what time and on which channel to watch the Ligue 1 match? Ligue 1: Luis Enrique leaves many PSG players to rest in Lorient

Ligue 1: Luis Enrique leaves many PSG players to rest in Lorient Football: Deschamps, Drogba, Desailly... Beautiful people with Emmanuel Macron to play with the Variétés

Football: Deschamps, Drogba, Desailly... Beautiful people with Emmanuel Macron to play with the Variétés Football: “the referee was bought”, Guy Roux’s anecdote about a European Cup match… with watches and rubies

Football: “the referee was bought”, Guy Roux’s anecdote about a European Cup match… with watches and rubies