For years, many people have perceived economic activity in Germany as a series of crises. The industrial transformation crisis was followed by the corona pandemic, then came the supply chain disruptions and finally in 2022 war, hyperinflation and energy shortages. Whether and when the Federal Republic will find an exit from this multi-crisis does not seem to be foreseeable at the present time.

As bleak as the view into the future is, a look in the rear-view mirror delivers surprising results. That look in the rear-view mirror gives at least a little hope, at least for large parts of the country.

A WELT evaluation of statistical data from 401 districts and urban districts (the local authorities) reveals that the Covid panic in 2020 did not depress German income as much as many had feared.

Statisticians always need a while to compile the numbers from all 294 districts and 107 urban districts. However, the results are also informative after a period of time, as they show trends or breaks in trends.

Among other things, the data from the local authorities that has now been released shows that Germans had more money to spend (or save) almost everywhere in 2020 than in the previous year.

At least that applies to disposable income, i.e. the money that is available to people minus taxes and social security contributions, but plus transfers such as child benefit or pensions. While primary income, i.e. what people earn through gainful employment or self-employment, fell by 1.7 percent per inhabitant across Germany in 2020, disposable income per capita improved by 0.7 percent - a modest increase, albeit above the general one price increase.

The pandemic undoubtedly brought with it great concerns about health and personal well-being, as well as restrictions on freedom, but most Germans did not have to accept any deterioration financially.

The relatively mild income development contrasts with the collapse in economic output during this period. In the first year of Corona, gross domestic product (GDP), the sum of all goods and services produced, fell by 4.6 percent.

Barring the 2009 financial crisis, this represents the biggest slump to date since World War II. Such a drastic decline would actually suggest shrinking incomes.

Apparently, however, increased short-time work benefits, corona aid and other welfare state measures have prevented disposable income from shrinking. The results are consistent with other statistics that show that Germans were able to save money overall in 2020, which can also be explained by the restricted consumption options due to the lockdown and travel restrictions.

On average, the disposable income per German citizen in the first Corona year was 23,752 euros. As positive as these results may appear at first glance, a second look reveals the burdens the crisis has placed on the backbone of the German economy, the manufacturing sector. In addition, the cushioned development had its price.

“The crisis that began in 2020 was one of the deepest crises of the post-war period. An even stronger economic slump was prevented by unprecedented stabilization measures by the state," says Gunther Schnabl, Professor of Economic Policy at the University of Leipzig.

According to him, the state quota jumped to 50.4 percent that year, compared to 45 percent in 2019. "The importance of state transfers for growth and thus for income has increased significantly in 2020."

Nevertheless, while the German population as a whole came through this phase of multiple crises relatively unscathed economically, it was the strong industrial regions that had to accept cuts.

The map of Germany shows that the regional authorities with declining incomes are concentrated in the south of Germany, where a particularly large number of medium-sized companies with international business are at home.

"Some of the differences can be explained by the different regional industry structures: The manufacturing industry is more important in western Germany than in the east, where services dominate, and it was more severely affected in 2020," says Maximilian Stockhausen, economist at the German Economic Institute (IW ) in Cologne.

Example Tuttlingen. The city in southern Baden-Württemberg is one of the medical technology centers in Europe. According to the municipality, more than 400 companies with around 8,000 employees are active in the industry.

Otherwise there are companies from the fields of mechanical engineering, food and luxury food production in the village. This healthy industrial base meant that disposable per capita income had risen by 3.2 percent in the ten years before the crisis, well above the nationwide figure of plus 2.4 percent.

Overall, there is a tendency that regions in which the economy was doing particularly well before the crisis had to cope with greater falls in primary income. "The state's measures focused on stabilizing collective wages, for example through short-time work benefits, as well as support payments (immediate and bridging aid) to companies, including small businesses," says the economist.

Income from additional wages such as overtime and extra shifts - which may have been the case in Tuttlingen - or income from sideline activities was not replaced: "Therefore, self-employed people such as landlords or artists also had to record high income losses".

Not surprisingly, tourist regions were also among the losers in the Corona crisis. "If, for example, there are many self-employed people living in a district like Starnberg, who suffered particularly from the closure of restaurants and entertainment events, then the drop in income was particularly large there," explains the economist.

It is remarkable that people in 2020 not only had to struggle more in industrial and medium-sized districts and in tourist areas, but also in “young” municipalities, i.e. cities and districts with a low average age. Incomes fell noticeably in the Lower Saxony districts of Cloppenburg and Vechta, for example, where the average age is below 41 years, around four years below the national figure.

On the other hand, municipalities with a high average age recorded a significant increase in income per inhabitant. In Dessau-Roßlau in Saxony-Anhalt and in Mansfeld-Südharz, the average age is almost 50 years. Here, disposable income rose by around four percent in 2020.

The increase in pensions on July 1, 2020 by 3.45 percent in the west and 4.20 percent in the east is likely to have contributed to higher increases in disposable incomes in the east, particularly in counties with older average populations. Collective agreements and pension increases extending into 2020 are likely to be responsible for the relative stability of disposable incomes, says Stockhausen, in both parts of the country.

Overall, the impression is that young people and families with children had a harder time in the 2020 crisis than areas where many older people live.

Measured in terms of the absolute level, quite a few East German regional authorities are lagging behind. In Halle (Saale), disposable income per capita was around 19,200 euros in 2020, a fifth below the national average. The lowest-income municipalities, however, are all in the West – deep in the West.

In Herne it was 18,800 euros, in Duisburg 18,400 and in Gelsenkirchen only around 17,600 euros. This contrasts with a high disposable income per inhabitant of 36,700 euros in Starnberg, followed by the Hochtaunus district with 33,600 euros, Baden-Baden with 32,000 euros and Munich with 31,900 euros.

The climber of the past decade was Rendsburg-Eckernförde. In the Schleswig-Holstein district between Kiel and Flensburg, disposable income per inhabitant has risen by 45 percent within a decade, faster than anywhere else in the republic. Amberg-Sulzbach in the Bavarian administrative district of Oberpfalz also managed an increase of more than 40 percent, as did Freyung-Grafenau and Straubing-Bogen in Lower Bavaria.

In 2020, however, the winning circles of the 2010s underperformed. This raises the suspicion that they could suffer particularly from price jumps, supply bottlenecks and energy shortages.

However, the state is trying to cushion the worst hardships in the never-ending multi-crisis. That should help many, with the difference that this time inflation is so high that there will only be losers, more or less big depending on the region.

"Everything on shares" is the daily stock exchange shot from the WELT business editorial team. Every morning from 7 a.m. with the financial journalists from WELT. For stock market experts and beginners. Subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Amazon Music and Deezer. Or directly via RSS feed.

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs

Spain is the country in the European Union with the most overqualified workers for their jobs Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation

Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application

Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application “I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing

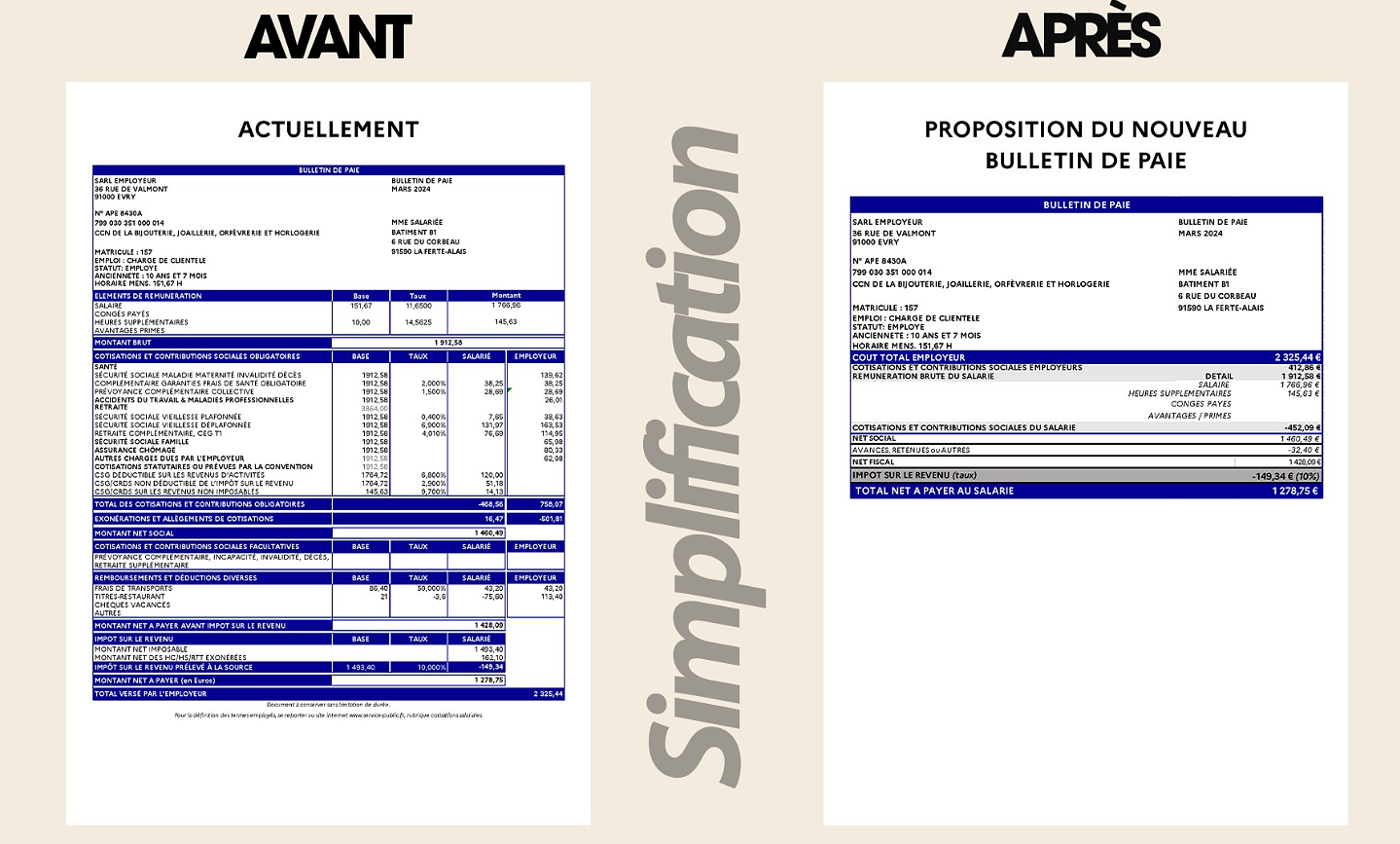

“I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy 25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits

25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan

At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga

Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker

Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops

OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet

Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid

Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid