Of course, China is a superpower. If you take the gross domestic product determined in all countries using uniform methods as a benchmark - the real GDP, which is based on purchasing power, i.e. what goods and services can actually be bought with money - the People's Republic has long since been back where it was always was and belongs according to its own self-image: namely right at the top of the world economy.

In the second half of the 2010s, China overtook the United States. The country's economic power is now around twenty percent higher than that of the USA and around five times higher than that of Germany. This means that conditions prevail again as they were before.

At that time, China was almost always in front and was successful and powerful over long stretches. Just 200 years ago, almost a third of global value added was generated in the Middle Kingdom, in Western Europe it was only around a fifth and in the USA just two percent.

Then followed two Opium Wars, which ended in 1860 in a crushing defeat for China. The British forced a radical opening of the Chinese market and established the crown colony of Hong Kong as a bridgehead. What followed was an economic disaster for the Middle Kingdom that lasted more than a century, comparable to the collapse of the East German economy after reunification.

Because the Chinese manufacturers, who were geared towards manual work, were hopelessly inferior to the imports from the West, because modern British machine production was far more effective.

China's share of world GDP halved from a third in 1820 to a sixth in 1870, falling to less than 10 percent at the beginning of the last century and less than 5 percent in the middle of the last century. With the loss of its international competitiveness, China lost its leading position first to Great Britain and later to the USA.

The caesura of the Opium Wars and their consequences have left an indelible mark on the collective memory of Chinese society. They have pushed the Middle Kingdom to the fringes of the global economy.

But they also wrote a lesson for the Chinese: learn as much as you can from the West, but distrust it as much as possible – forever.

This lesson led to the People's Republic dancing peacefully and obediently to the tune of the West. China became a member of the World Trade Organization in 2001, a US-founded and Western-influenced body that adheres to the doctrine that the rule of law, not the rule of law, should govern international relations.

At the Communist Party Congress in China, President Xi called on the population to "prepare for the worst cases". He threatened Taiwan with military action. Welt editor Stefan Aust hopes that Xi will learn from the Ukraine war.

Source: WORLD / Stefan Aust

The result was China's integration into globalization and a historically almost unprecedented catching-up process. In the 1990s, Germany and China were still equal – with about a quarter of the US economy.

China's real GDP tripled in the 2000s and doubled in the 2010s. For comparison: in Germany, real GDP increased by a third in the noughties and by 40 percent in the 2010s.

But again, China's opening up and entry into the world economy was a forced marriage, not a love marriage. And the no-Covid strategy now made a good case for a return to lockdown, isolation and closing borders.

“The zero blockade has restricted freedom of movement inside and outside the country: Chinese scientists almost no longer attend conferences abroad; Chinese executives hardly ever travel anymore; the number of European emigrants in China has halved,” writes the British weekly magazine The Economist in its current issue.

The turn from globalization to isolation has its price: Real economic growth in the People's Republic has never been lower than it is today since 1980. 2020's 2.2 percent is a four-decade record low, the current year's 3.2 percent is the second-worst result, and the International Monetary Fund's current outlook from mid-October falls at around 4.5 percent for the next few years, anything but bright.

In plain language, this means that the Chinese process of catching up with the West has lost momentum, despite all claims to political power. Because despite the sheer size of all the macroeconomic data, China has remained a sedentary giant to this day. A giant when it comes to the big picture. But still a comparatively weak candidate when the living conditions for the bulk of the population are compared. A great deal has improved, but there is still a lot to do.

The average Chinese has about a third of the purchasing power of an average American. This puts the success story of the communist people's republic into perspective compared to the capitalist model of the USA. And even compared to crisis-ridden Germany, the differences remain huge.

The real purchasing power per person in this country is still three times higher than in China. That, too, is a comparison that puts the different situations in perspective, even if that shouldn't and shouldn't be an excuse for Germany not to get significantly better.

The backwardness in living conditions is also the reason why the People's Republic is still treated as a developing country in the World Trade Organization - and as such not only demands privileged special treatment in trade.

The national economy is still financially supported by Germany within the framework of development cooperation. In view of the political power and military strength of China, for many this is an old platitude that is hard to understand and should actually be done away with.

The economic weakness in the People's Republic represents an additional risk for global economic policy. "It is cold consolation that China is weaker than it appears. Much weaker powers can also be dangerous, as Russia under President Vladimir Putin has shown. A more isolated, inward-looking China could become even more warlike and nationalistic,” says The Economist.

For Germany, the current developments require a reorientation. Away from dependencies on Chinese customers, out of the cluster risk China and back to a Western alliance that stands for a global economic order that treats all countries legally equally and on an equal footing. It is high time to strengthen a transatlantic partnership not only in the military, but also in the economic dimensions of trade, investment and innovation.

Thomas Straubhaar is a professor of economics, in particular international economic relations, at the University of Hamburg.

"Everything on shares" is the daily stock exchange shot from the WELT business editorial team. Every morning from 7 a.m. with the financial journalists from WELT. For stock market experts and beginners. Subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Amazon Music and Deezer. Or directly via RSS feed.

Sydney: Assyrian bishop stabbed, conservative TikToker outspoken on Islam

Sydney: Assyrian bishop stabbed, conservative TikToker outspoken on Islam Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases”

Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases” Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK

Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years

In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years WHO concerned about spread of H5N1 avian flu to new species, including humans

WHO concerned about spread of H5N1 avian flu to new species, including humans New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria

New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting

Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence

The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence Bitcoin halving: what will the planned reduction in emissions from the queen of cryptos change?

Bitcoin halving: what will the planned reduction in emissions from the queen of cryptos change? The Flink home shopping delivery platform will be liquidated in France

The Flink home shopping delivery platform will be liquidated in France Bercy threatens to veto the sale of Biogaran (Servier) to an Indian industrialist

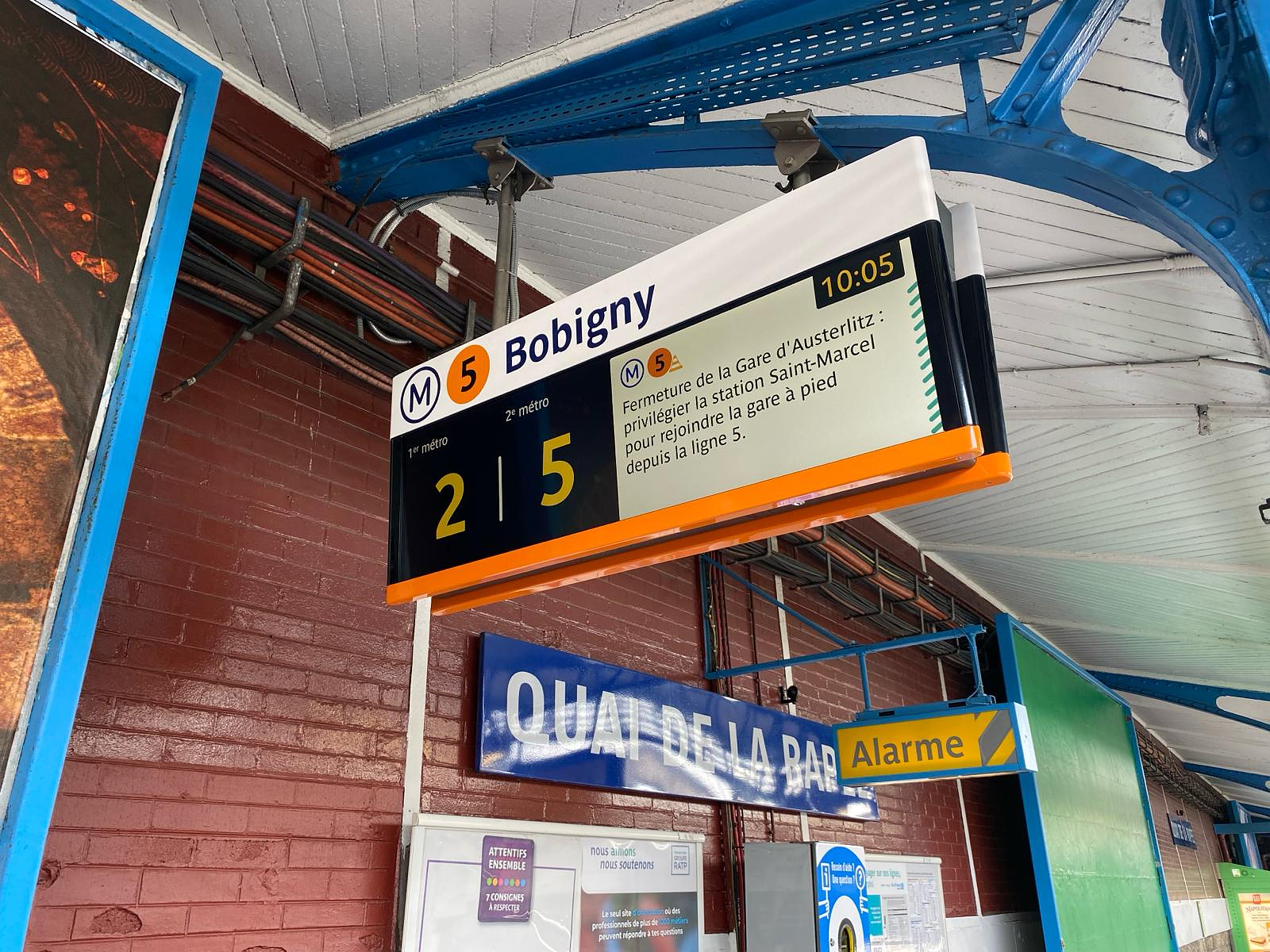

Bercy threatens to veto the sale of Biogaran (Servier) to an Indian industrialist Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF?

Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF? Who’s Who launches the first edition of its literary prize

Who’s Who launches the first edition of its literary prize Sylvain Amic appointed to the Musée d’Orsay to replace Christophe Leribault

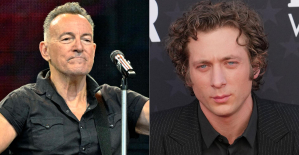

Sylvain Amic appointed to the Musée d’Orsay to replace Christophe Leribault Jeremy Allen White to play Bruce Springsteen for biopic

Jeremy Allen White to play Bruce Springsteen for biopic In Los Angeles, Taylor Swift hides clues about her new album in a library on the street

In Los Angeles, Taylor Swift hides clues about her new album in a library on the street Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie

During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Tour of the Alps: Simon Carr takes on the 4th stage of the Tour of the Alps, marked by a big scare

Tour of the Alps: Simon Carr takes on the 4th stage of the Tour of the Alps, marked by a big scare Cycling: in video, Chris Harper's big scare on the 4th stage of the Tour des Alpes

Cycling: in video, Chris Harper's big scare on the 4th stage of the Tour des Alpes Football: Mathieu Coutadeur will retire at the end of the season

Football: Mathieu Coutadeur will retire at the end of the season Athletics: young Tebogo says African sprinters will dominate the season

Athletics: young Tebogo says African sprinters will dominate the season