In times when there is a lot of talk about critical infrastructures, the word "supercritical" is particularly in need of explanation. Physicists coined this term to describe a special state of matter.

In 1822, the French scientist Baron Charles Cagniard de la Tour discovered that liquids sealed in a pressure vessel become “supercritical fluids” above a minimum temperature and pressure. It is then no longer possible to distinguish whether it is a liquid or a gas. A supercritical fluid is as dense as a liquid and yet as inviscid as a gas. So it has a small viscosity.

For example, bringing water to its supercritical state requires a temperature of at least 374.12 degrees Celsius and a pressure of at least 221 bar. Supercritical water has significantly different properties than normal water. These are specifically exploited in various technical applications. There are coal-fired power plants that work with supercritical water in the steam process because this increases efficiency. Supercritical water is also used as a solvent. Substances can also be decomposed in this way without having to use strong acids or alkalis.

Now scientists at the University of Washington report the development of a reactor that can use supercritical water to destroy dangerous organic substances that are very difficult to destroy with other methods. Specifically, it is about the chemically very stable per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS), which are used in many industrial processes due to their technical properties and are also contained in commercial products.

The compounds perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) play a special role. If they get into the environment, they do not decompose there even after very long periods of time. They are now detectable in the food chain and also in humans. The extent of the health risks they pose is a matter of debate.

There is evidence that these substances impair the immune system. In any case, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) reassessed the health risks of PFAS in food in September 2020. Accordingly, people should take in a maximum of 4.4 nanograms (ng) of these substances per week and kilogram of body weight.

Of course, it would be better not to let them get into the environment in the first place. The Washington researchers headed by Igor Novosselov report that their technology can be used to destroy PFOA and PFOS molecules in industrial wastewater. "First of all, our reactor can heat water very quickly," explains Novosselov, "but unlike in an ordinary saucepan, it can also be heated to temperatures well above 100 degrees Celsius." Together with high pressure, this creates supercritical water. "This is chemically so aggressive that organic molecules cannot survive in this environment."

The researchers designed the reactor in such a way that the substances to be destroyed can be fed in continuously. After just 30 seconds, the problem substances have completely broken down into water, carbon dioxide and fluoride salts - salts that are also contained in toothpaste. The PFOS molecules turned out to be more stable and persistent than the PFOA molecules. While these can already be destroyed at just under 400 degrees Celsius, the controller must be turned up to at least 610 degrees Celsius for the PFOS.

Researchers initially focused on PFOS and PFOA because the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency wants to give concrete support to measures to remove these substances from the environment. But in principle, according to the researchers, their reactor with supercritical water is also suitable for destroying other problem organic substances. Wherever they have accumulated in the environment, they could, in principle, be destroyed with this technology. But of course everything has its limits. "We will not be able to rid the entire ocean of pollutants with this," says Novosselov.

"Aha! Ten minutes of everyday knowledge" is WELT's knowledge podcast. Every Tuesday and Thursday we answer everyday questions from the field of science. Subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Deezer, Amazon Music, among others, or directly via RSS feed.

Sydney: Assyrian bishop stabbed, conservative TikToker outspoken on Islam

Sydney: Assyrian bishop stabbed, conservative TikToker outspoken on Islam Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases”

Torrential rains in Dubai: “The event is so intense that we cannot find analogues in our databases” Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK

Rishi Sunak wants a tobacco-free UK In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years

In Africa, the number of millionaires will boom over the next ten years WHO concerned about spread of H5N1 avian flu to new species, including humans

WHO concerned about spread of H5N1 avian flu to new species, including humans New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria

New generation mosquito nets prove much more effective against malaria Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting

Covid-19: everything you need to know about the new vaccination campaign which is starting The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence

The best laptops of the moment boast artificial intelligence Bitcoin halving: what will the planned reduction in emissions from the queen of cryptos change?

Bitcoin halving: what will the planned reduction in emissions from the queen of cryptos change? The Flink home shopping delivery platform will be liquidated in France

The Flink home shopping delivery platform will be liquidated in France Bercy threatens to veto the sale of Biogaran (Servier) to an Indian industrialist

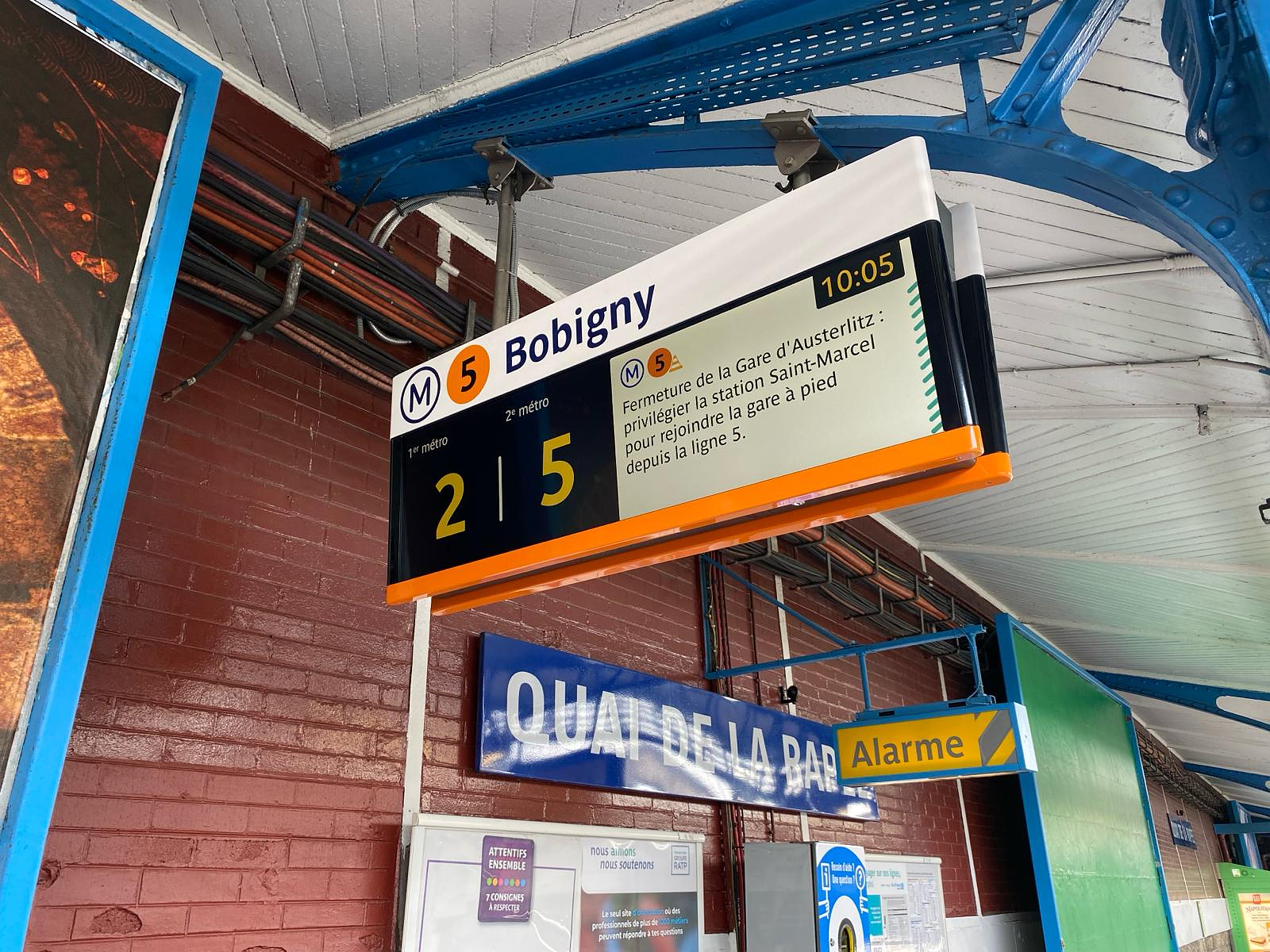

Bercy threatens to veto the sale of Biogaran (Servier) to an Indian industrialist Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF?

Switch or signaling breakdown, operating incident or catenaries... Do you speak the language of RATP and SNCF? Who’s Who launches the first edition of its literary prize

Who’s Who launches the first edition of its literary prize Sylvain Amic appointed to the Musée d’Orsay to replace Christophe Leribault

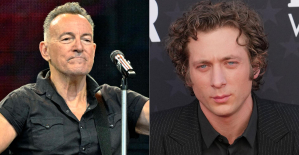

Sylvain Amic appointed to the Musée d’Orsay to replace Christophe Leribault Jeremy Allen White to play Bruce Springsteen for biopic

Jeremy Allen White to play Bruce Springsteen for biopic In Los Angeles, Taylor Swift hides clues about her new album in a library on the street

In Los Angeles, Taylor Swift hides clues about her new album in a library on the street Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy

Europeans: “In France, there is a left and there is a right,” assures Bellamy During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie

During the night of the economy, the right points out the budgetary flaws of the macronie These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Tour of the Alps: Simon Carr takes on the 4th stage of the Tour of the Alps, marked by a big scare

Tour of the Alps: Simon Carr takes on the 4th stage of the Tour of the Alps, marked by a big scare Cycling: in video, Chris Harper's big scare on the 4th stage of the Tour des Alpes

Cycling: in video, Chris Harper's big scare on the 4th stage of the Tour des Alpes Football: Mathieu Coutadeur will retire at the end of the season

Football: Mathieu Coutadeur will retire at the end of the season Athletics: young Tebogo says African sprinters will dominate the season

Athletics: young Tebogo says African sprinters will dominate the season