Even though Napoleon had experienced his Waterloo in 1815, there were quite a few who saw their great role model in the famous general. One of them was a man whose family was intricately linked to the rise of the Corsican: Ibrahim Pasha (1789–1848), eldest son of Mehmed Ali, the Ottoman viceroy of Egypt.

This had originally been a tobacconist in Kavalla in Thrace. He had come to Egypt in 1801 as the leader of an irregular force to help drive out the last of the French led by Napoleon Bonaparte on his Egyptian expedition in 1798. The French general had defeated the Mamluks, Muslim war slaves who had ruled the Nile for centuries. But then nature, the Ottoman resistance and last but not least the British fleet proved to be overwhelming opponents, so he returned to take power in France as First Consul.

In the ensuing power struggle in Egypt, Mehmed Ali demonstrated his political talent, played off one opponent after the other and was finally appointed governor by the Sultan in Istanbul. When he invited the leaders of the Mamluks to a banquet in Cairo in March 1811 and had them put to the sword there, his son Ibrahim stood by his side as a docile student. From then on, both dedicated themselves to the goal of modernizing the country based on the European model.

Their most important tool was the army, which was upgraded by Western instructors to become the most powerful military power in the Levant. Grinding his teeth, the sultan had to deign to recognize Mehmed Ali as a de facto autonomous ruler for life.

In 1821 the great uprising against Ottoman rule broke out in Greece. Although the Greeks only had guerrilla fighters at their disposal, they managed to get large parts of the country under their control by 1825. When Sultan Mahmud II asked for military support in Cairo, this was also based on the political motive of weakening the viceroy, who had become too powerful. The fact that he nevertheless accepted the offer had to do with the opposite calculation: by conquering Greece he would gain a stepping stone to Europe and thus possibly be able to shake off Ottoman supremacy.

Mehmed Ali appointed his son Ibrahim as commander-in-chief of the expeditionary force. Until then, he had distinguished himself in the fight against the Mamluks and in campaigns in the Sudan and on the Arabian Peninsula. He landed in Greece in 1825 with 56 warships and 150 transports with 16,000 infantry and 2,000 horsemen. Within a few months, the Greek uprising was on the verge of catastrophe.

The Egyptian troops, reinforced by Turkish units, marauded through the valleys, conquering the long-besieged Mesolongi and finally Athens. With a systematic "campaign of annihilation" Ibrahim Pasha separated the Greek guerrilla fighters from their supporters. “Flying columns passed through Messenia and Arcadia; the previously spared villages went up in flames, 60,000 fig and 25,000 olive trees were cut down, the livelihood of future generations was destroyed in advance,” wrote the German historian Carl Mendelssohn Bartholdy in his great “History of Greece”.

This warfare proved successful on the ground, but it also mobilized European public opinion against the Ottoman Empire. England, France and Russia sent fleets off the Greek coast. This may have been directed against the principles of the Restoration advocated by the Austrian Chancellor Metternich. But even the Tsarist Empire, where after the death of Alexander I, a new man came to power in the person of Nicholas I, no longer wanted to turn a blind eye to the suffering of the "Orthodox brothers".

In the London Protocol, the three great powers agreed in July 1827 to end the "anarchy in Greece" by force of arms if necessary. However, Sultan Mahmud II, with final victory in mind, let it be known "that the Sublime Porte would not accept any proposal regarding the Greeks". At the same time, Ibrahim Pasha intensified his scorched-earth strategy to end the war by winter.

The British Admiral of the Mediterranean Fleet, Edward Codrington, was in command of the ten ships of the line and twelve frigates with a good 1,200 guns. His destination was the Bay of Navarino, ancient Pylos in the south-west of the Peloponnese. There, the Turkish-Egyptian fleet, a total of 82 ships with 2000 guns, gathered to take action against the last pockets of resistance in the Aegean.

Codrington decided to hold his demonstration on October 20th. He had instructed his captains "not to fire a cannon ... until the signal to do so was given". However, should "a Turkish vehicle allow itself to fire a shot, it should be shot at and immediately destroyed". One can imagine the nervousness of everyone involved when the Allies entered the narrow bay under the guns of the Turkish fortress, lined up and ready for action, and approached the Turks within pistol shots.

At around 2:30 p.m., when a British frigate asked a Turkish boat to distance itself, shots were fired. Several Englishmen died. The Allies immediately struck back. In a confined space, one salvo of their modern artillery was often enough to disable an enemy ship. In this last major naval battle, which was only fought with sailing ships, the Ottomans and Egyptians lost a battleship, twelve frigates, 22 corvettes and 25 other ships within a few hours.

Prisoners had not been taken. "The exasperation that prevailed at this battle, fought in the midst of peace, was too great," writes Mendelssohn Bartholdy. The Allies counted 172 dead and 470 wounded, their opponents lost around 6,000 men.

The Egyptian army had remained intact, but had to suspend operations in the winter due to poor supplies and the lack of a fleet. The Tsar's soldiers took care of the rest. In 1828 he declared war on the Sultan. The Ottomans owed it only to English and French pressure that Nicholas I stopped the march on Istanbul and concluded the Peace of Edirne. In it, the sultan also had to agree to the London Treaty of 1827, albeit to the effect that the new Greek state - the Peloponnese, the mainland up to Volos-Arta and some Aegean islands - should not become autonomous, but sovereign.

Ibrahim Pasha had not been present during the battle. The rumor was that the Egyptians wanted to dodge a decision on the demands of the great powers. He soon found a new field of activity in Syria, which he conquered in 1833. As governor, he implemented a modernization program that included equal rights for Muslims and Christians. In 1841, however, the great powers forced his retreat. In poor health, he died before his father in Cairo in 1848.

You can also find "World History" on Facebook. We are happy about a like.

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff

Germany: Man armed with machete enters university library and threatens staff His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction

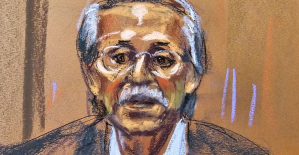

His body naturally produces alcohol, he is acquitted after a drunk driving conviction Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial?

Who is David Pecker, the first key witness in Donald Trump's trial? What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain?

What does the law on the expulsion of migrants to Rwanda adopted by the British Parliament contain? Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024

Parvovirus alert, the “fifth disease” of children which has already caused the death of five babies in 2024 Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50

Colorectal cancer: what to watch out for in those under 50 H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States

H5N1 virus: traces detected in pasteurized milk in the United States What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated)

What High Blood Pressure Does to Your Body (And Why It Should Be Treated) Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation

Insurance: SFAM, subsidiary of Indexia, placed in compulsory liquidation Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application

Under pressure from Brussels, TikTok deactivates the controversial mechanisms of its TikTok Lite application “I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing

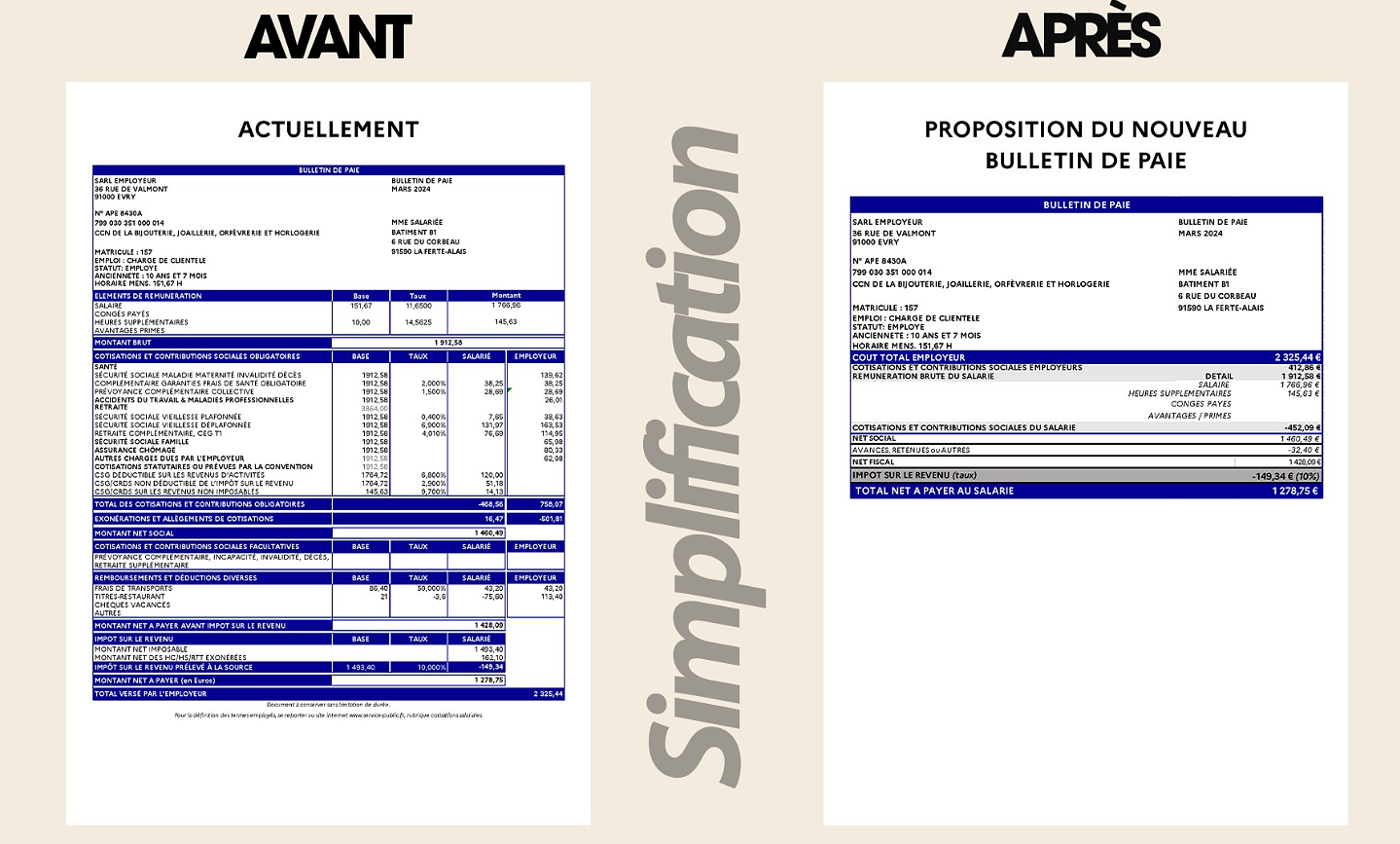

“I can’t help but panic”: these passengers worried about incidents on Boeing “I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy

“I’m interested in knowing where the money that the State takes from me goes”: Bruno Le Maire’s strange pay slip sparks controversy 25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits

25 years later, the actors of Blair Witch Project are still demanding money to match the film's record profits At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan

At La Scala, Mathilde Charbonneaux is Madame M., Jacqueline Maillan Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga

Deprived of Hollywood and Western music, Russia gives in to the charms of K-pop and manga Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker

Exhibition: Toni Grand, the incredible odyssey of a sculptural thinker Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV

Skoda Kodiaq 2024: a 'beast' plug-in hybrid SUV Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price"

Tesla launches a new Model Y with 600 km of autonomy at a "more accessible price" The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter

The 10 best-selling cars in March 2024 in Spain: sales fall due to Easter A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars

A private jet company buys more than 100 flying cars This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade

This is how housing prices have changed in Spain in the last decade The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46%

The home mortgage firm drops 10% in January and interest soars to 3.46% The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella

The jewel of the Rocío de Nagüeles urbanization: a dream villa in Marbella Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down?

Rental prices grow by 7.3% in February: where does it go up and where does it go down? Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron

Sale of Biogaran: The Republicans write to Emmanuel Macron Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou

Europeans: “All those who claim that we don’t need Europe are liars”, criticizes Bayrou With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition

With the promise of a “real burst of authority”, Gabriel Attal provokes the ire of the opposition Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9

Europeans: the schedule of debates to follow between now and June 9 These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar

These French cities that will boycott the World Cup in Qatar Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League

Hand: Montpellier crushes Kiel and continues to dream of the Champions League OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops

OM-Nice: a spectacular derby, Niçois timid despite their numerical superiority...The tops and the flops Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet

Tennis: 1000 matches and 10 notable encounters by Richard Gasquet Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid

Tennis: first victory of the season on clay for Osaka in Madrid